This was usually done near the mine to avoid carrying waste materials. It was also very labour intensive and employed boys, old men and, sometimes, women in order to reduce costs. The vein-stuff sent from the mine was a mixture of ore, rock, clay and other minerals. Apart from hand-picking any clean lumps of ore from it, the rest was ‘dressed’ to separate the lead ore.

Bouseteams

On leaving the mine the vein-stuff was placed in a hopper, some of which had a small flow of water dropped into them to begin the dressing process. This began washing off clay and sand from the mix before it was pulled from the front of the team onto a grid of iron bars set about 25 mm apart. Stuff that went through the bars went to the crusher, while lumps too big to pass were broken up using a sledge hammer.

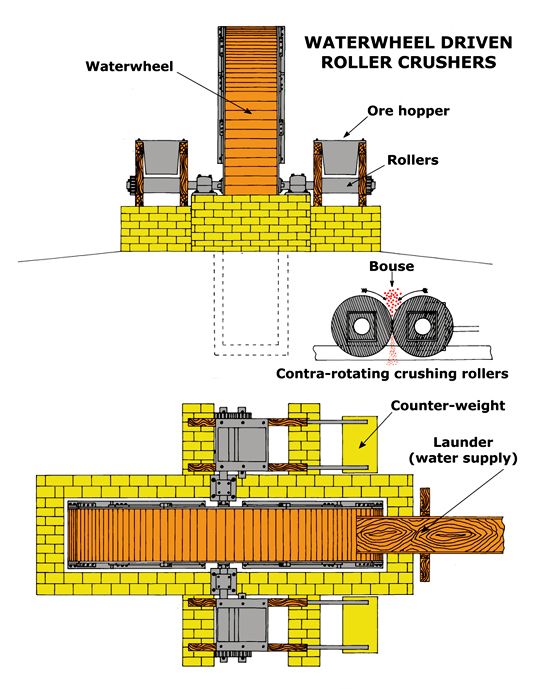

Crushing

Before the 1800s lumps of ore-bearing rock were broken by hammers and ore rich material was washed in a controlled flow of water. The lead ore, being heavy, was less mobile than other rock and could easily be collected.

Before the 1800s lumps of ore-bearing rock were broken by hammers and ore rich material was washed in a controlled flow of water. The lead ore, being heavy, was less mobile than other rock and could easily be collected.

Larger mines began to mechanise their dressing operations from the early 1800s, introducing waterwheel powered roller crushers to break ore-rich material into a uniform size (around 10 mm). The graded material was then washed in hotching tubs, with progressively finer material being treated in buddles and dolly tubs. Even the dirty water was channelled to settling tanks to maximise the retrieval of any ore it might contain.

Hotching tubs

These had a rectangular box, suspended from a long forked lever, and submerged in an oblong tub of water. The box’s base was a trellis of strong iron wire which formed a mesh of 10 mm squares on which the ore was placed. A youth held the lever and jumped up and down vigorously, thus shaking the sieve in the water. With each shake, the respective positions of the fragments of feed were changed according to their relative density and some of the finest fell through the mesh. As a result, the feed was eventually separated into three layers. The purest and heaviest parts were concentrated at the bottom, against the sieve, with fragments of ore mixed with stone above them. The uppermost layer consisted pieces of stone and gangue minerals. The top layer was slimmed off and thrown away. The middle layer went for further crushing, and the bottom layer went to the smelt mill.

After the introduction of roller crushers it became necessary to mechanise the hotching process in order to treat the large quantity of finer feed they produced. By the mid-1820’s brake-sieves driven by water-wheels were being installed at some mines. This cut costs, by reducing the amount of labour needed, and allowed poorer ores to be worked.

After the introduction of roller crushers it became necessary to mechanise the hotching process in order to treat the large quantity of finer feed they produced. By the mid-1820’s brake-sieves driven by water-wheels were being installed at some mines. This cut costs, by reducing the amount of labour needed, and allowed poorer ores to be worked.

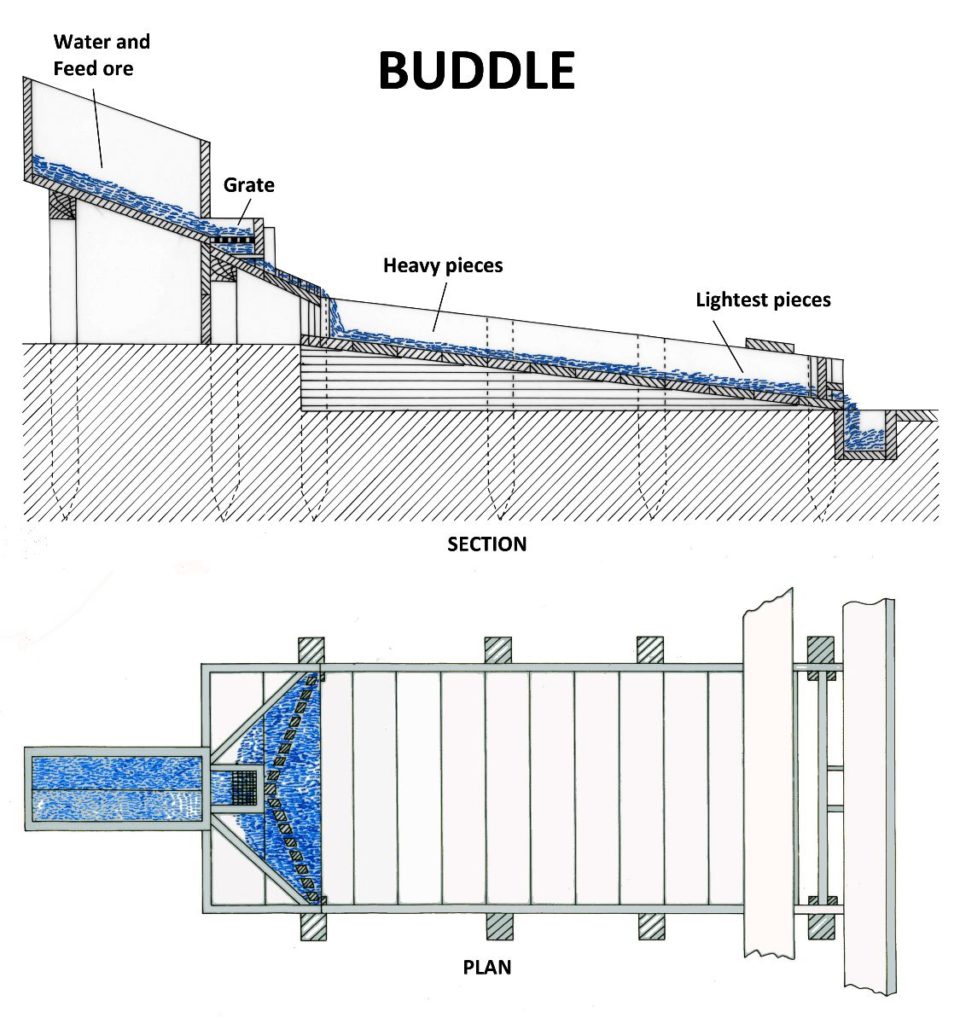

Buddling

The material which passed through the sieve into the base of the hotching tub was treated in a buddle. This used a steady flow of water to wash the lighter material along a large, nearly flat surface to separate it from pieces of ore. The latter was sent to the smelt mill, the former went to the tip.

Dolly Tub

This was like an old rinsing tub and it was used to treat the finest silt from settling pits. The slurry was put into the tub and agitated using a paddle. It was then left to settle, with the heaviest particles (lead ore) going to the bottom and lightest (rock, clay etc.) staying near the top, with a mixture in the middle. Sometimes the side of the tub was hit with a hammer to encourage settlement.

All dressing floors left spreads of finely crushed material on which little or nothing will grow. Mechanised dressing floors were larger and typically have a row of bouse teams, a wheel pit and a series of terraces on which the washing machinery stood.

Return to previous page