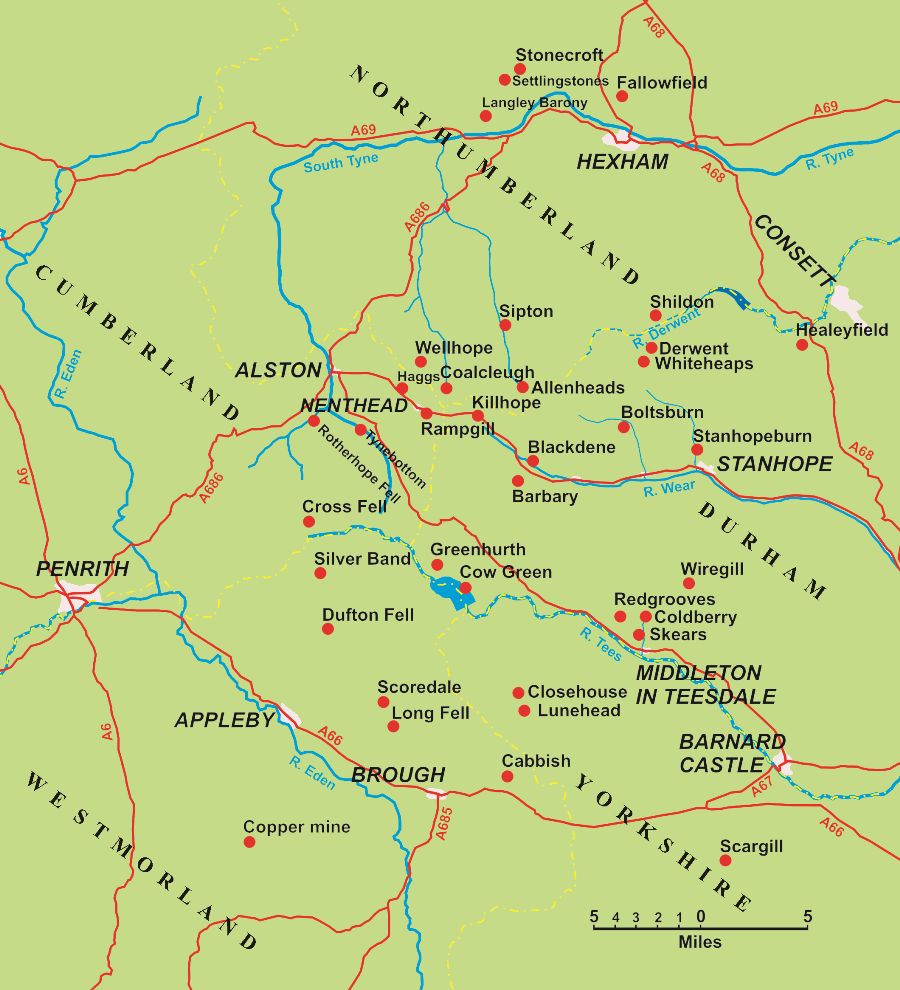

This orefield was England’s largest producer of lead and silver by the nineteenth century and runs from the A66 in the south to Hadrian’s Wall in the north, and from the western escarpment to the edge of the coalfield in the east. This incorporates parts of the old counties of Yorkshire, Westmorland, Cumberland, Durham and Northumberland. The ore came from the various limestones, especially the Great, and some sandstones in the 550 metres of strata from the Melsonby Scar limestone up to the Low Fell Top limestone.

The area also had many rich flats, where the limestone surrounding a vein was replaced by mineralisation, especially lead and zinc. In some places, however, flats were rich in iron minerals.

With a few exceptions the lead industry here was dead by the 1920s, but mining and dump workings for fluorspar and barytes survived. Fluorspar was especially important in the Weardale-Rookhope area, and near Hunstanworth until the 1990s. Barytes was more important on the west fringe of the orefield, from upper Teesdale and along the escarpment in the Eden Valley. Some barytes was also worked from veins found in collieries in the west Durham coalfield.

Alston Moor

There had been earlier attempts at working the silver-rich lead ores found on Alston Moor, but the crown let it mines there in the mid-thirteenth century. Various lessees worked the mines until 1629, when they were acquired by the Radcliffe family, later Earls of Derwentwater, and were said to be nearing exhaustion. Around 1700 the London Lead Company, which was run by Quakers, got its first leases on Alston Moor and bought a smelt mill near Whitfield.

Following the 3rd Earl of Derwentwater’s execution for his part in the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 his estates were forfeit and in 1735 they were bestowed on the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich. The mines were offered for lease in 1736, when the bulk of them were signed over to Liddle & Co. Having failed to make a profit, this company sold its Nenthead smelt mill and some of its leases to the London Lead Company. This body steadily expanded its grip on the mines and became involved in the local community, building schools, chapels and much of Nenthead village.

The veins in the Great Limestone and the beds above it could be reached by driving levels from the valley sides. Some veins were associated with flats, where the mineralisation had spread into the surrounding rocks, which were rich in lead ore. The lead from some of the veins was also rich in silver and the company developed processes for separating the two metals profitably. The London Lead Company worked its mines in a comprehensive manner and systematically searched for new deposits of ore. In consequence the area has an extensive network of horse levels and crosscuts. Nevertheless, the company did not monopolise the area and others, both large and small, operated there too.

Following the low price of lead in the 1870s the London Lead Company decided to concentrate on its mines in Teesdale and to sell its Nenthead mill and its leases to the Nenthead and Tynedale Lead and Zinc Company in 1882. The latter was able to raise zinc ore from the old lead workings, and a period of higher prices for that metal allowed it to make a profit. Nevertheless, the output of lead fell and the company sold its leases to the Vieille Montagne Zinc Company, of Belgium, in 1895. At Nenthead, the average number of men employed underground fell from 332 per year in the 1890s to 180 in the years running up to World War I. The numbers of surface workers were 139 and 155 respectively. The mine closed in 1920.

At the company’s other mines, Nentsbury had an average of 23 men per year working underground and seven on the surface between 1896 and 1913, and 36 underground with 32 on the surface between 1915 and 1943, when it was discontinued in December. Rodderup Fell had an average of 14 men per year working underground and nine on the surface between 1896 and 1913, and 15 underground with 13 on the surface between 1915 and 1945, when it closed.

Durham

The principal centres of lead mining in this county were in Teesdale and Weardale, where most of the ore came from similar strata to those found in the mines of east Cumberland.

The Bishop of Durham, owner of the minerals in upper Weardale from the mid 12th century, formalized earlier arrangements in 1566 by letting them to a Moor Master who oversaw the allocation of mining rights and the collection of dues. In return, the miners paid one-tenth of their output, in dressed ore or its monetary value, to the Bishop, plus another tenth to the local parson. They were also obliged to sell their ore to the Moor Master at a discount on the current market value. The latter kept the difference.

The Blackett family began leasing Weardale mines in 1675 and steadily built up its interests to become the principal operation in the area, with a number of highly profitable mines. Through marriage the Blackett mines passed into the Beaumont family around 1830. The low lead prices of the 1870s forced the closure of the Beaumont’s Weardale mines in 1883, but its leases were taken over by the Weardale Lead Co. Ltd

As well as lead, this company produced increasing amounts of fluorspar for use as a flux in iron making. Nevertheless, in 1900 the board voted to wind up the Weardale Lead Co. Ltd and to register a new company with the same name to carry on its business. Relying increasingly on fluorspar production this company worked until 1962, when ICI took a controlling interest.

The North Pennine fluorspar zone is centred on Weardale and during the 19th century the area supported a number of mines working this mineral, with lead ore as very much a by-product. This industry died out in the 1980s as world prices fell and the national steel industry was reduced in preparation for privatisation.

Ironstone deposits were associated with some Weardale veins, and the coming of a railway allowed these to be worked from the 1840s until the 1920s. The ore was mainly carried onto the coalfield for smelting.

Lead mining in Teesdale was dominated by the London Lead Company, which took its first lease there in 1753 and moved its headquarters to Middleton in Teesdale in 1815. The latter, at Middleton House, was built to the design of Ignatius Bonomi, who later designed workers’ housing at Masterman Place. Its major mines were between Eggleston and Newbiggin Commons, but it had others around the head of the valley and around Lunehead.

The London Lead Company agreed to dissolve in July 1902 and quickly began divesting itself of its mines and other assets. By 1905 it was out of Teesdale.

Northumberland

Again, most of the ore came from the same strata as those found in the mines of Cumberland and Durham. There were, however, fewer lead mines in this county, and most of them were in the Tyne Valley or its tributaries. Exceptions were the mines at Blanchland and those in the Allendales.

One mine, at Settlingstones, was a large producer of an uncommon mineral called witherite (barium carbonate). Because of its solubility in common acids, witherite is preferred to barytes in the preparation of other barium compounds. It is also used in case-hardening steel and in refining sugar. The mine closed in 1969.

Return to previous page