Haematite occurs in near vertical veins running nearly north-south across the valley. In the last century it was thought that these veins were the “mother lode” from where the iron ore deposits of Cleator Moore and Millom had orginated; just below the surface the veins of poor ore would open upinto vast iron deposists. Modern thought is that the iron solutions trickled down from above – the iron comes from the red sandstone – and replaced the calcium carbonate both of the limestone belt surrounding the fells and of the the veins cutting across the fells. Thus the iron ore tends to die out quite quickly as you go deeper in the fells.

Haematite occurs in near vertical veins running nearly north-south across the valley. In the last century it was thought that these veins were the “mother lode” from where the iron ore deposits of Cleator Moore and Millom had orginated; just below the surface the veins of poor ore would open upinto vast iron deposists. Modern thought is that the iron solutions trickled down from above – the iron comes from the red sandstone – and replaced the calcium carbonate both of the limestone belt surrounding the fells and of the the veins cutting across the fells. Thus the iron ore tends to die out quite quickly as you go deeper in the fells.

The iron ore deposits, reddish in colour, outcrop on the surface and must have been used for “ruddle” or pigments since early times. Iron has been smelted in the valley since at least Roman times, as the many small banks of slag testify. Presumably local ore was used. Considerable quantities of iron ore were taken from the top of Wasdale screes round about 1700 by a man called Patrickson. The Penningtons at Muncaster were making trials on a vein in the deer park in 1759 and 1760, while various histories and guides report the existence of iron ore in the area.

However, in Eskdale proper mining seems to get under way in 1837 with a lease to James Read & Co for the area north of the Esk. By 1841 seven mines are listed in the Eskdale census. By 1842 royalties were being paid on 373 tons, 8 cwt of iron ore from Eskdale, raised by Borker & Co. Mr Borker was a prominent Whitehaven businessman who also worked mines at Bigrigg near Egremont at about this date. Ore was shipped from Ravenglass to South Wales which came from Nab GIll mine at Boot.

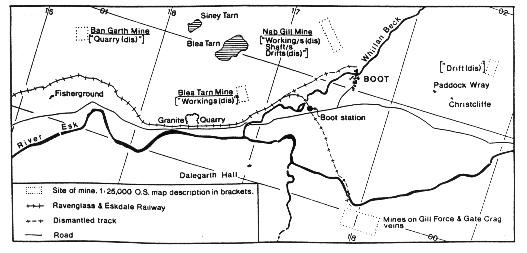

Later in 1845 the Lindow brothers leased the Eskdale mines. They worked the area from 1845 to 1853, and raised a few thousand tons of ore, but for little profit. They worked mainly at an open quarry on the fell top behind Fisherground Farm, the Ban Garth Mine, but also drove two short barren levels into the fellside at Nab Gill. In1860-63 Jos. Fearon, another Whitehaven businessman, took up the lease. He drove a new level into the fellside below the Ban Garth opencast, and raised a disappointing 1000 tons of ore. He proposed building a wooden tramway down the valley to reduce the cost of transport. In 1866 he sold the lease to Faithful Cookson, iron master of London, who was an astute operator with good connections. In co-operation with a Devon miner, W H Hoskings, he bought the leases of various West Country and Welsh iron mines at about this time. He also acquired the lease of iron ore mines in Ennerdale as well as Eskdale.

In the early 1870′s demand for steel was increased by the Franco-Prussian War. Only Cumbrian haematite ore was suitable, and available in quantity, for producing steel by the Bessemer process. The price rose to 35/- a ton, with mining costs typically of only 5/- a ton. Furness and Cleator Moor became the richest mining areas in the world. Faithful Cookson made considerable sums of money by forming mining companies which then bought the mine leases from him.

The Eskdale and Ennerdale leases were worked by the so-called Whitehaven Mining Co Ltd. There were almost no local shareholders though – locals were too wise about the prospects. The company was widely advertised in the press, with glowing reports from Hoskings about the iron ore being found in veins 40 feet wide. This was true, but the portion of the vein which was iron ore was often only a few inches wide. The company had an imposingly respectable board of directors, but all were either very busy men in other walks of life or very unknowledgeable about mining. Cookson still owned most of the shares though he sold many of them on the Stock Exchange. Mining in Eskdale was started only slowly, though there were plans to build a tramway from the mines to the nearest railway station and port at Ravenglass. The shareholders, thinking (quite rightly) that this tramway would never carry enough ore, insisted that the directors survey the route as a standard gauge branch line.

After 2 years or so, in about 1873, Cookson was rumbled. The directors were mainly replaced and Cookson parted from the mine company in acrimonious circumstances, though not before having made about £25,000 on the venture. The new board decided to continue mining as the ore price was still high, and also to build a narrow gauge railway up the valley. A gauge of 3 feet was chosen, the most recommended narrow gauge for railways at the time, The mine at Nab Gill was very carefully managed, equipped and laid out, and a start was made on the railway. However, the mines never really made any money, even with ore prices of 30/- a ton. By the time the railway was completed to Boot in 1875, ore prices were falling and the numerous levels driven down the hillside had shown just how little ore was present.

The Ban Garth mine was also briefly re-investigated, and some ore raised on a new vein further east called Blea Tarn, behind Beckfoot Station on the railway. By 1877 however the mining company was in voluntary liquidation and being worked by a receiver, as was the railway. In the next few years the receiver leased the mines to several consortia formed by the Owens, Father and Son, mining engineers from Bristol. They withdrew in about 1883, though a few miners and the railway manager worked the Boot mine on a small scale to about 1885.

Meanwhile, on the south side of the Esk, another London company leased the iron ore rights in the 1870′s, but nothing more is known about them. The Owens, however, noticed an iron vein at Gill Force near St.Catherine’s Church. In 1880 this was leased by a group led by a civil engineer called William Donaldson, who had worked on the new Midland Railway line around Bristol. The group was financed by the sons of the Midland Railway’s General Manager, James and Howard Allport. It called itself the South Cumberland Iron Mining Co at one time. A branch line of the railway was built to this mine, and extensive mining operations carried out in 1880-81. However this mine soon ran out of ore. Despite extensive trials on veins on the south side of the Esk and also on the north side, east of Boot village, behind Christcliffe and Paddockwray farms, it had folded by 1884.

Ore prices were now only 8/6d a ton, and the mines were hopelessly uneconomic. Many of the miners were West Country men who moved to Millom where many of their fellows were employed. The railway somehow struggled on with a small amount of traffic in granite for road setts, building materials for the new villas being built at Eskdale Geen, agricultural traffic and tourists. It was probably the poorest railway in the country!

The Nab Gill mine was briefly reopened in the 1907-12 period, when the workings were taken below the valley floor, but the iron ore vein grew ever thinner and the ore poorer. The railway also struggled on, ever more decrepit, but after the mines closed in December 1912, the railway finally closed in April 1913. It was relaid to a narrow gauge of 15″ in 1915 and re-opened. High iron ore prices during the First World War caused the mines to briefly reopen in 1917 and close again in 1918, this time for good.

There were a few other small iron ore trials in Eskdale and neighbouring Miterdale, but none of these was very important. In total the valley produced perhaps 100,000 tons of iron ore over the centuries. This was the tonnage the railway was built to carry in one year. Probably only Faithful Cookson ever made any major profits out of these mines.

Albyn Austin

Return to previous page