One man and his clay pipe might be a slightly exaggerated view of the population of Tredegar before the Industrial Revolution, but only marginally so. A few farms, a few pubs, a few churches and a few more pubs were the sum total of man’s presence with no notable settlements of any significant size. The human species normally kept to the hilltops, a visitor to the area in the late 18th Century, Archdeacon Coxe, commented:

“As we proceeded the vale expanded and numerous farmhouses with small enclosures of corn and pasture occupied the slopes. The whitened walls and brown stone of the detached buildings gave an air of neatness and gaiety to the surrounding landscape.” He continued to state “The small cottages are all provided with a garden, and some are enabled to keep a cow which ranges the commons for subsistence. The comforts are increased by the abundance of fuel, whether coal or wood, which abounds every part of the country….the condition of the peasantry in Monmouthshire is very advantageous.”

Evolution, Divinity, Mother Nature or whatever, must have decided that life was becoming boring and decided to liven things up a bit by making man more aware of the wealth of minerals under this land and of the uses that they could be put to. The modern iron age was about to explode onto the scene, explode being the correct adjective, because this progressive and innovative nature of mankind was driven not by the commitment to increase the living standards of humanity, but more to increase the dying standards of inhumanity. To the delight of man, and no doubt to the dismay of every other living creature in the area, the ingredients for making iron; ironstone, limestone, wood, water, and later coal were discovered easily accessible along the northern rim of the area. By the end of the 18th century, the woods had disappeared, and man decided to pursue to dead trees of a hundred million years ago, burrowing deep to find their ancient graves so that by 1775 coal was being used instead of charcoal. Iron making now easily outstripped the transport facilities available, i.e. the pack mule, and new methods of transportation were required. The Newport to Crumlin branch of the Monmouthshire Canal was opened in 1794 and linked to the works at Tredegar and Ebbw Vale by tram roads. The Borough was now wide open to exploitation on a massive scale, the port of Newport beckoned and the iron masters responded. The days of tranquillity were now just a fond memory.

Iron, iron, iron, iron for the railways and factories of the rapidly expanding British Empire, for the guns to fight Napoleon, or to fight the rebellious Americans, iron had become the industrial master with coal its servant. Soon the servant was to oust its master, and coal was to reign supreme, but for now iron was King, the area between Hirwaun and Blaenavon was to become the centre of the UK, and therefore the World’s iron-making industry. The Hirwaun Iron Works opened in 1757, the Dowlais Iron Works opened in 1759, and the Cyfarthfa Iron Works in 1769. This development rapidly continued with the construction of further works at Penydarren, Rhymney, Tredegar, Sirhowy, Ebbw Vale, Beaufort, Blaina, Nantyglo, Victoria, Clydach and Blaenavon. This area, little more than 18 miles long and one mile wide, supported fourteen great works that in varying degrees thrived until the trade for iron rails to the USA was stopped in the 1870s by the US Government.

In Blaenau-Gwent in 1796 there were three furnaces producing 3,927 tons of iron, by 1825 these figures had risen to twenty-four furnaces producing 61,940 tons of iron, and in 1840 there were twenty-seven furnaces producing 83,378 tons of iron.

As early as 1760 a Mr. Kettle had a small furnace at Sirhowy, and in 1778 Charles Henry Burgh leased land to Thomas Atkinson of Yorkshire, and late of Carolina, and his three partners; William Barrow, Bolton Hudson and John Sealey, who were “tea men and grocers of Threadneedle Street, London”, with a contract for forty years at an annual rate of £134. They were to “build so many furnaces, forges, foundries, mills, engines, storehouses and buildings that were necessary for the placing and keeping of iron ore, coal and charcoal and for the making and manufacturing of iron, with full liberty to make weirs and impound the water of the Sirhowy or any other brooks.” This was the first coke-fired furnace to be built in Monmouthshire. Early production was between 4 to 6 tons of pig iron a week it is employing 50 men by the 1790s. Following the failure of the works it was taken over by Richard Fothergill and Matthew Monkhouse in 1794 who installed a second furnace and a steam engine in 1797 and increased production to 100 tons per month, employing 50 men in the 1790s. By 1817 three furnaces were producing 2,000 tons of iron. They acquired a small iron works at Llanelly Hill and the limestone workings at Trefil which they connected by Tramroad to Sirhowy and later to Crumlin and the head of the Monmouthshire Canal, the latter part costing £30,000 to construct. The cast iron rails for these roads were made at Sirhowy and were the first rails to be made in Wales.

The lease expired in 1818 and a dispute over renewal arose between Fothergill and the lease owners who were now the Ebbw Vale works owners; Harford, Partridge & Co. Fothergill refused to pay the new sum of £2,500 per annum and either removed or destroyed all the equipment at the Works. A lawsuit ensued in which Fothergill had to hand over £6,000 in compensation. The Sirhowy Iron Works were then worked in conjunction with the Ebbw Vale Works and by 1840 four furnaces were in production giving an annual production of 7,000 tons. From then on, the Sirhowy Works were gradually absorbed into the Ebbw Vale Works.

In 1799 the owners of the Sirhowy Works, Richard Fothergill and Matthew Monkhouse joined forces with Samuel Homfray, William Thompson and William Forman with a capital of £30,000 to start the Tredegar Iron Works. It was built on land owned by Sir Charles Morgan with an annual rent of £300 for the first five years and then £500 per year for the rest of the 99-year lease. They were granted a lease “of all the coals and mines under Bedwellty Commons and the lands bound on the north by Nantybwch, on the east by the Sirhowy River, on the south by Pont-y-Gwaith yr Harn, and on the west by the part of Bedwellty Common adjoining the River Sirhowy.” They were given the right to construct a Tramroad down the valley to join the canal at Crumlin provided they used Lord Tredegar’s wharf at Newport and hired his boats for any iron to be sent to Bristol. Any necessary sand, timber or coal could be purchased from him. £40,000 was invested in the Works with two furnaces being put into blast by 1803 each producing 35 to 50 tons of pig iron a week. The puddling and rolling mills were in operation by 1807 when output was 4,000 tons of iron. The No.4 Furnace came on blast in 1809 and the No.5 Furnace in 1817 raising the production of iron to 10,000 tons a year. The Company then decided to develop the finished product and started the manufacture of large bars and rods.

Richard Fothergill retired in 1818 (he died in 1821) and his son Rowland took charge, in 1829 he introduced a steam locomotive into the works. Designed by George Stephenson and named Britannia it made two journeys a week to Newport carrying a load of 80 tons at speeds of up to 6 miles per hour. In 1830 the Works had 5 furnaces and produced 18,514 tons of iron. The demand was so high for the iron rails made at Tredegar that they adopted Neilson’s 1828 patent for using hot blast instead of cold air in the furnace therefore increasing production. By 1840 these works had shipped 363,822 tons of iron down the Monmouthshire canal, the peak year being 1838 when 15,526 tons of iron was transported down the canal. It wasn’t until 1883 that the Tredegar Works converted to steel making and by that time the company was basically a coal-producing one, the importance of the works had become secondary. The first method for moving the iron products to the customer was tram roads running to the Crumlin Branch of the Monmouthshire Canal. The Aberbeeg Tramroad ran to Nantyglo, the Beaufort Tramroad served Ebbw Vale and the Sirhowy Tramroad operated to the Tredegar area. They were provided for in the Monmouthshire Canal Act of Parliament which stated “railways, wagon ways or stone roads to Blaenavon, Trosnant, Blaendare, Ebbw Vale, Sirhowy, Aberbeeg and Nantyglo” to provide “an easy and commodious communication into divers Iron Works, Lime Stone Quarries, Woods of Timber Trees, and Collieries in the neighbourhood of Pontnewynydd and Crumlin Bridge.” This canal was eleven miles long to Newport it had 31 locks which raised the canal up by 358 feet. It opened in 1797 and used barges 60 feet long which carried a load of 25 tons. They took a whole day to travel the length of the canal. Amongst the shareholders for the canal were the Duke of Beaufort, Samuel Glover, the Harfords, and Sir Charles Morgan. They had been empowered to raise a capital of £120,000 with a share value of £100 each and an option to raise another £60,000, although the final cost was expected to be £108,000. The project was so popular that shares had risen to £450 by 1793. In total between 1802 and 1840, the canal shipped 1,388,269 tons of iron from the Iron Works of Blaenau Gwent.

The canal was not the ideal solution to the transportation problems, it became short of water in the summer and could be frozen in the winter, it just couldn’t cope with the demand for its services and a backlog often jammed the wharf at Crumlin. The tramways/railways solved these problems, one of the first public services in South Wales ran between the Sirhowy Furnace and Cwmfelinfach as early as 1805, with the Monmouthshire Canal Company’s tram roads carrying passengers from 1822. The Newport to Crumlin tramline was opened in 1829 and linked the tram roads from Blaina and Ebbw Vale directly to Newport. The Act of Parliament of 1845 saw the transformation of Monmouthshire lines from tram roads to railways, this meant the end for mixed methods of haulage, i.e., horses and steam locomotives from now on it was steam locomotives only. The Western Valley line (Newport to Blaina) was opened to passengers in June 1850, it took 105 minutes to travel the full distance, with the passenger service from Newport to Ebbw Vale commencing in 1852. The Sirhowy Tramroad was converted to a railway in 1860 with its name changing from the Sirhowy Tramroad Company to the Sirhowy Railway Company. A new standard gauge line was constructed with diversions being made at Tredegar, Argoed and Blackwood to avoid the main shopping centres The rapid influx of workers into Ebbw Vale, Tredegar, Nantyglo and Blaina brought about a housing shortage. During the period 1801 to 1841, the population of the Tredegar area increased from 619 to 22,417, the largest rate of increase in the UK It needed upwards of 200 men were required to work one blast furnace, with the iron masters constructing terraces and terraces of cottages to accommodate their workers. A report of 1847 states that a typical cottage rarely has more than one room which is used for both living in and sleeping. “A large dresser and shelves usually form the partition between the two.” The water supply would be from the nearest stream and the toilet would be a hole in the ground. There was little or no sanitation and these conditions regularly caused outbreaks of plague, with severe cholera epidemics in 1832 and 1848. Living and working conditions were appalling, between 1821 and 1841 for every 1,000 children baptized 479 under the age of five years died. Yet despite this, the Tredegar Town Centre was well planned out, and the Tredegar Iron Company arranged free education for the children of its workers.

This was literally the melting pot, fights between the races were common, there was no social security, no dole money little hope. Yet still they poured into the area looking for a better future. Life was barely tolerable when work was plenty, but when trade slackened it was pitiful. Some of the masters tried to help; Fothergill and Monkhouse of the Sirhowy Iron Works would provide a communal kitchen when work was slack but most were indifferent to the suffering. Women were forced into prostitution, children begged in the streets along with the maimed of the works, men turned to thieving or became violent drunks. Yet out of this chaos came a determination to better themselves, and the workers began to organise themselves and unite in some of the bitterest social confrontations that these islands have ever seen. Smelters, puddlers and forge men were the elite and often commanded a house, a fire and drink, skilled men were put on piece work or time worked plus bonuses, with finermen and hammermen serving long apprenticeships, but the labourer were paid by the day. Payment was around 2/6d a day in 1796 but due to the French Revolution and the fear of war, a furnace keeper could earn between 22/6d to 27/- by 1805. Good times or bad, you had to have your wits about you working in the Iron Works as poor old William Walter found out in 1829. The Monmouthshire Merlin newspaper reported in December of 1829:

“whilst in the act of emptying his barrow of mine (iron ore) into the kiln below, fell into it and although his fellow workers were on the spot they could afford him no assistance as the clinker broke that was on the surface where he fell when he was instantly completely hidden by burning materials. On Saturday some of his calcined bones were taken out of the kiln.”

The young women who toiled in the works had other dangers to worry about, very often they were thought to be the playthings of the masters, in nearby Blaenavon immorality in the coal mines between men and women by 1850 had become so widespread that the manager tried to stop women and girls working in them (the fact that they had been banned from working underground in 1842 hardly mattered) a riot ensued and the poor man only just escaped with his life. From then on official company policy appears to have been that it was impossible, due to the many entrances to the levels, to prevent women from entering the mines and helping their men folk. The dragger girls that worked in the levels were no doubt viewed with less affection. They were harnessed in straps and chained, along the lines of horses, and worked on all fours in the dark and damp and low and frightening tunnels for up to sixteen hours a day. Many of these girls were killed in one instance in 1830 an eight year old girl died underground alongside her father and five others when the level that they were working in was flooded. The weekly wage for a 12 or 14 hour day during 1830 to 1839 for children and women in our area were: up to 7 years of age 7.5 to 10p. 7 to 10 years of age, 12.5p to 17.5p. 10 to 12 years of age, 17.5p to 22.5p. 12 to 15 years of age, 22.5p to 35p. 16 to 21 years of age, 35p to 55p. Dragger girls were paid 17.5p to 32.5p. Women were paid 60p to 72.5p. Male miners earned between 90p and £1.05p. Wages were a little better within the Iron Works: Labourers would receive between 57.5p to 72.5p Furnacemen received between £1.25 and £1.35, Roller men, £1.50 to £1.60, Carpenters, 90p to £1.05, while Masons received between 90p and £1.05 a week. It took until 1842 and the Children’s Employment Commission to produce a Mines Act that banned women, and children under ten years of age from working underground. Not that made any difference both continued to work for at least a decade after the Act until a method of enforcement was introduced. This Commission carried out a thorough investigation and reported that children often started work as early as age six years, either opening ventilation doors in the mines or as limestone breakers or lookers-on in the iron works. The poor wages of that time often compelled men to supplement their pay by bringing their wives and children into the levels with them, all too often the owners would coerce the man into using his family by either making it a condition of employment or allotting extra trams to be filled by that man. The younger boys were employed opening and closing ventilation doors to allow the passage of the dragger girls, often the mother or sister, to pass through. As early as the age of nine or ten he would progress to a collier. For both the hours of work would be from around 4am to 9pm during weekdays, with in some places the Saturday shift starting at midnight. Many died or were maimed through accidents brought about by fatigue or negligence. In 1860 an enlightened Government banned children from under 12 years of age from working underground.

The remoteness of the Iron Works and mines of this area meant that there were very few shops except those that were provided by the owners. With the exception of Tredegar most owners refused to allow small merchants to open shops on their land, there were difficulties in trans-porting goods over the rough terrain that were the valleys, and the lack of Banks in the new districts created a shortage of money, all this added together gave the Iron Masters a virtual monopoly on goods and created the hated Truck System. The Iron Masters paid out the wages on a monthly basis, in arrears, which meant that the workers were always in debt, they could go to the company store and receive an advance on their wages in the form of goods and settle up on payday, invariably with the result that their wages did not cover the cost of the goods received which were around 20% to 30% dearer than in other shops. This system thereby tied the worker to the company until the debt was paid, making him a virtual slave. As the Works and the population of the area grew the Masters paid out in their own currency which in many cases could only be redeemed in the company shop (the exception again being Tredegar). Understandably this version of serfdom was hated by the workers and the first time that troops were brought into the area was in 1800 when the workers of neighbouring Penydarren looted their Truck Shop. They were also a regular target of the Scotch Cattle who would raid the shops and destroy the records.

In 1829 a report into the Paying of Workmen’s Wages in Goods stated that “the practice was common in the hills of Monmouthshire, and that payment was sometimes made in ale so that other tradesmen, e.g. shoemakers, were unable to obtain payment.” In 1832 the Anti Truck Act prohibited the payment in certain trades of wages in goods or otherwise than in current coin of realm. The truck system was still reported to be in action in Ebbw Vale as late as 1871. At Tredegar, the company shop never had a monopoly, and the company currency, including the famous 1812 Token Penny was accepted in all trading establishments. Even Sir Charles Morgan of the Tredegar family was totally against the truck system. The year of Our Lord 1800, was a bad one, besides the rioting in Penydarren, the poor harvests had created a shortage of food in the area, at Beaufort two hundred people held up pack horses carrying barley and the local population rioted out of control for an hour. In the same year, many bread shops in the locality were systematically looted, and work came to a halt in the Iron Works due to a trade recession. It was also the beginning of a long and turbulent period in our history; the workers and their families were living in filth, working in filth and generally treated as filth were now becoming united and organised and started to fight back. The property clause of that time debarred most of these people from electing members of Parliament, the Courts were controlled by the Gentry and the Iron Masters, and the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800 banned associations of workmen in attempting to raise wages, reduce hours, or otherwise improve conditions.

Brutalized by the living and working conditions, and treated as disposable commodities by the rich and powerful they had only one recourse to justice. They Rioted. In 1802 the Ironmasters Association was formed (their Union wasn’t banned) with the aim of holding quarterly meetings to discuss the price of iron, and no doubt other matters. Riots broke out again in 1810 due to a shortage of bread and in 1816 there was another slump in the iron trade, the masters posted notices that wages would once again be reduced, and short-time working was introduced. The fact that striking was illegal and could result in transportation to the other side of the World was ignored by the workers at the Tredegar Iron Works, every man, woman and child, downed tools, the workers at the Sirhowy Iron Works soon joined them and the first strike was on. They decided to march to Merthyr Tydfil to seek the support of the Dowlais, Penydarren, Plymouth and Cyfarthfa workers. Pre-warned by Samuel Homfray the owner of the Tredegar Works, the owner of the Dowlais Works, John Guest manned Dowlais House with men armed with pikes and guns. The marchers were in a good mood as they marched unwittingly into the guns of Dowlais House, several men fell wounded, and one died later that day. The crowd surged past Dowlais House and onto the Works where they were greeted as heroes. The Dowlais workers joined them, then the Penydarren workers, followed by the workers at Cyfarthfa and the Plymouth Works. All the great works of Merthyr had stopped production. The following morning this army of strikers returned to Tredegar and besieged the company shop to demand bread and cheese which was hurriedly handed over to them. They then marched to Beaufort and Ebbw Vale, down to Newbridge and Abercarn and Crumlin, and back up to Nantyglo and Blaenavon. Everywhere the result was the same, everyone downed tools. Soldiers were sent into the area but everything remained quiet, one week turned into two, and still the strike held, hardships were nothing new to these people, they worked for next to nothing and had learned to live on next to nothing. A meeting was called between some of the local magistrates and the strikers’ representatives at Bassaleg. The magistrates reported back to the owners and the notices were withdrawn. The workers had won. They had won the right to wait for the crack of timber in that dark mine that heralded a roof fall and their mutilation or death, they had won the right to return to the furnace and the splatter of white-hot searing metal on their skins, they had won the right to wait until the masters were ready for revenge. Resentment over the hated truck shop culminated in major demonstrations in 1831, the discontent simmered on into 1831 when besides this the workers heard that the Reform Bill had been passed in Parliament and that wages were to be reduced. Merthyr Tydfil simply erupted; there were 9,000 workers in the four main works alone, and together with the miners then took control of the Town the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders tried to restore the Iron masters peace shooting dead approximately 26 rioters and injured another 70 outside of the Castle Hotel yet still the insurrection continued, the following morning more soldiers delivering ammunition from Brecon were driven back and the Swansea Yeomanry on approaching the Town were disarmed and routed. It finally took 800 soldiers and four days to restore a semblance of order. Twenty-eight workmen were sent for trial, with two; Lewis Lewis (Lewis the Huntsman) and Richard Lewis (Dic Penderyn) were sentenced to death. Lewis Lewis was reprieved but the 23 year old collier, Richard Lewis who was accused (probably falsely) of wounding a soldier was hanged at Cardiff Goal in August 1831 still protesting his innocence.

In 1832 the Iron Masters posted notices stating that no one belonging to a Union Club (Benevolent Club) would be employed at any of the works from then on and that they would close the works down if they were not disbanded. More disturbances ensued and once again the military was called in. After seven weeks of strikes, the men were starved back to work. The workers being defeated in open battle unwittingly resorted to similar tactics employed by the Silurians of this land in that long-gone era of sparkling streams and green valleys. They resorted to hit-and-run tactics operated by a clandestine organisation called the Scotch Cattle.

Even to this day little is known about the Scotch cattle or even the origins of the name, such was the secrecy surrounding this 19th century urban guerrilla group. It claimed in 1834 to have 9,000 members in and around the “Iron Belt” of the north and as far south as Blackwood/Crumlin/Pontypool. Not known for their subtle approach, they completely dominated the Borough during the 1830s and early 1840s. Notices such as this posted at the Tredegar Iron Works went a great way to convince the workforce to toe the Scotch Cattle line.

Take Notice.

The Poor Workmen of Tredegar to prepare yourself with Musquets, Pistols, Pikes, Spears

and all kinds of Weapons to join the Nattion and put down like torrent all Kings, Regents,

Tyrants, of all description and banish out of the Country, every traitor to this Common

Cause and to bewry famine and distress in the same grave.”

The Cattle were formed into herds of approximately 200 to 300 members, each herd covering a particular area and headed by a leader called a Bull. There is no evidence of a central leadership but the co-ordination between the herds was so effective that there must have been some sort of control. Their meetings and “visits” were noisy affairs and were accompanied by drums, horns and the firing of guns in an attempt (mostly successful) to intimidate and terrify their opponents or victims. Members used to turn their coats or wear animal skins, black their faces and visit miscreants outside of their own area to avoid detection. It was originally formed to protect the rights of colliers, and to control the number of colliers to within their close-knit circle, it expanded to encompass all injustices to the working classes in the Iron Belt. Towards the end of its existence, some claimed that it had degenerated into nothing more than a band of thugs and thieves. Its origins were in the Welsh section of the communities, notices were in the Welsh language, and meetings were also held in Welsh, within the latter days English interpreters were allowed. It was also racist in attitude towards the Irish immigrants who tended to work for lower wages and therefore, they claimed, undermined the solidarity of the workers. Strike-breakers or people who worked for lower wages and poorer conditions were its main targets, although the Cattle were not averse to intimidating company agents, landlords, bailiffs, toll keepers, shopkeepers, or destroying tram roads or company property. In fact, they would attack anything or anyone who represented authority. Before a visit they always gave a written warning to give the person a chance to fall in line with the rest of the workers, with the aim of the visit to terrify and pillage, the furniture in the house would be completely wrecked, and the windows and doors smashed, only with the most recalcitrant of persons was violence offered, although accidental injuries and even death occurred. They seem first to have appeared in 1822 during a thirteen-week strike of that year when they ripped up miles of Tramroad between Crumlin and Abertillery and burned wagons and canal barges. Despite being guarded by the Chepstow Yeomanry and the Scots Greys a horse-drawn coal train was attacked in the Ebbw Valley and thirty wagons were damaged. Two members, Josiah Lewis of Nantyglo and Harri Lewis of Ebbw Vale, were gaoled for rioting over this incident. The power of the Cattle grew tremendously until in 1834 it was reported that Law and Order had completely broken down between Dowlais and Blaenavon. In that year a ringleader was captured in Pontypool and promptly freed by a mob. Often owners were afraid to prosecute in case of retaliatory actions and disputes were called off on the promise of the release of captured Cattle members. They were very adept at enforcing solidarity during strike actions as in January of 1830 when a depression in the iron industry forced the price of coal down from 50 pence per ton to 40 pence per ton. The owners posted notices to drop wages and half of the Welsh furnaces were shut down. By March of that year, all of the Monmouthshire colliers (including those not directly employed by the Iron Masters) were on strike for a wage of 50 pence per week and the abolition of the Truck System. At a mass meeting at Croespenmaen just to the south of the Borough, the owners agreed to the strikers’ terms and the strike ended. In 1832 the owners of the Blaina, Nantyglo and Coalbrook Vale Works lowered wages by 5% and violent strikes broke out again, the managers’ house was stoned, strike-breakers were attacked and a red bulls head was painted on the doors of their houses. In February over 200 herd members attacked two cottages, broke the windows, smashed the furniture and beat the men of those households, in April the herd visited a Nantyglo worker’s home in Abersychan and wrecked his house. The military was brought in and a sum of £15 was posted as a reward for information on the Cattle. Although £15 was a magnificent sum for those times there was not one taker. It is interesting to note that the officer in charge of the troops reported that the blame for the discontent was the abuse of the Truck System by the owners. The violence and intimidation continued through that turbulent time in our history, in 1833 at Blaina, a strike-breaker, although supposedly protected by the military had his legs broken in his own home in front of his family. The miners at Risca had agreed to work for reduced wages but changed their minds after being visited by the Herd. In July 1834 Thomas Rees a shopkeeper at the Rock near Blackwood had his ledgers ripped up by the Cattle, in January of 1835 he was visited again and this time he was beaten and his belongings destroyed. Two of the Cattle were this time recognised by a servant of Rees’ and were condemned to death this sentence was later commuted to transportation. Edward Morgan was not so lucky, again in 1835, and again following an incident in Blackwood when a woman died, he was hanged at Monmouth Goal for murder. From 1835 a combination of an increase in the iron trade, the formation of trades unions and the rise of Chartism brought about the end of the activities of the Scotch Cattle, although sporadic flare-ups appear to have continued until around 1858.

The People’s Charter was drafted by William Lovett of London and published on the 8th of May 1838. The Charter called for universal manhood suffrage (voting), equal electoral districts, annual parliaments, vote by secret ballot, the abolition of the property rule for MP’s, and payment for MP’s. The first Chartist petition was presented to Parliament on the 14th of June 1839 and consisted of 1.5 million signatures. Parliament rejected this petition by 237 votes to 48 votes and sparked off a wave of strikes and riots throughout the United Kingdom. In May of 1842 a second petition was presented to Parliament which consisted of 3,315,000 signatures, but it was rejected by 287 votes to 49 votes. Further strikes occurred and more leaders were arrested. The movement continued to agitate until 1848 and then faded into history. In 1839 there were 400 active Chartists in Newport mainly in the newly emerging middle class. Their leader was John Frost, a former magistrate and Mayor of Newport, who had thrown all his energy into the Chartist cause. He was joined in that January by Henry Vincent of London, Vincent had been sent down by the London Workingmen’s Association and was very often accompanied on his travels around the valleys by Doctor William Price of cremation fame, and the movement in Monmouthshire began to spread into the industrialised valleys. By February of that year, the valleys were afire with hope that at last a way had been found to get out of their miserable lifestyle. Branches or Lodges were formed in Blackwood, Pontllanfraith, Tredegar, Ebbw Vale, Beaufort, Blaina, Brynmawr, Dukestown, Abersychan and Llanhilleth, with an active membership estimated to have been 20,000. In April of that year, massive rallies were held throughout Monmouthshire, and 8,000 attended a meeting at Newport even though it had been declared illegal. By May the authorities were really worried, 15,000 names had been collected for the National Petition from Merthyr and Blackwood alone, and further attempts were made to ban meetings with troops being based at Newport, Abergavenny and Monmouth. A dozen soldiers deserted and were converted to the Chartist’s cause. The authorities issued arrest warrants for the leaders including Vincent who was arrested in London and brought back to Newport. His arrest caused a wave of disturbances at Newport and further demonstrations at Hirwaun, Pontypool and Nantyglo. Henry Vincent was sentenced to one year in prison, William Edwards got nine months, and John Dickenson and William Townsend both received six months in goal. John Frost was not arrested and continued to make plans for a massive demonstration and march planned for November 1839. Whether this march on Newport was planned to be an uprising or just a peaceful protest is unclear, some of the Chartists stated it was the beginning of the revolution, others said it was not. Some eminent historians say it was, others say it was not. It is clear that many of the marchers, perhaps the majority, didn’t know what the hell was going on, and many were forced to join in. It is also known that in October pike-heads and guns were made in secret in preparation for the events to come. Vincent is also known to have talked about an uprising and the Republic of Wales.

This momentous march on Newport commenced on Sunday, November 3rd 1839 with a column from Blackwood headed by Frost and including men not only from the Blackwood area but from Tredegar and Rhymney as well. A column headed by Zephaniah Williams consisting of the men of Sirhowy, Ebbw Vale and Nantyglo marched down the Ebbw Valley, (Zephaniah Williams used to be the mineral agent to the Sirhowy Iron Works, and as such lived a relatively comfortable life, he gave this up for the Chartist Movement and became the Innkeeper at the Royal Oak Inn at Nantyglo) and a column from Pontypool headed by William Jones came down the Afan Lwyd Valley. It is estimated that in total there were 5,000 men involved. Frost started off at 7pm and took part of his column to Newbridge and down the Ebbw Valley, the rest of the Blackwood men proceeded down the Sirhowy Valley. The Nantyglo and Ebbw Vale men met at 6pm but had to wait until 9 pm for the Sirhowy contingent. The Pontypool men left at about 10 pm firstly shutting down the works in the area and generally terrorising anyone who hadn’t joined. The contingents of Frost and Williams met and rested at Risca and the Welsh oak and set off again at 7 am the following morning. The Pontypool contingent never arrived at Newport, instead, they waited outside of the Town. Why is unclear, some believed they were held in reserve, and others believed that they were waiting to see which way the wind was blowing before joining in. Whatever the reason, when they heard that the demonstration had ended in disaster they broke up and fled.

Meanwhile, at Newport, a company of seventy troops under Captain Richard Stack had been billeted in a workhouse. On hearing of the supposed insurrection, the Mayor and his councillors had ensconced at the Westgate Hotel in the middle of the Town and called up 60 special constables to protect them. A detachment of soldiers consisting of two sergeants and 28 privates under the command of Lieutenant Grey was dispatched from the workhouse to join them. At 9.20 pm the Chartists marched down Commercial Road and headed for the Westgate Hotel. It appears that as the crowd pressed near to the Hotel a special constable tried to grab a pike from one of the Chartists and a general scuffle broke out. Shots were fired, from what side is not known, and the front rank of the Chartists attacked the Hotel and forced their way into the lobby. Several of the Specials then panicked and ran and the situation deteriorated rapidly. The soldiers opened fire on the crowd outside and forced them back, they then opened fire on the Chartists in the lobby and drove them out of the Hotel. Altogether the violence lasted 25 minutes and resulted in several soldiers being injured and even the Mayor had gunshot wounds. On the Chartist’s side 22 were killed, including one of the soldiers who had deserted, and fifty were injured.

The uprising, revolution, insurrection, demonstration or whatever one wants to call it was over, most of the Chartists returned home whilst the leaders went into hiding. A reward of £100 was posted for the capture of the leaders. Twenty-nine were captured and committed for trial. Twenty-one were charged with high treason at the trial which started at Monmouth on the last day of 1839. On the 16th of January 1840 eight of these were found guilty, including Frost, Williams and Jones, and were sentenced to the civilised punishment of; being drawn on a hurdle to the place of execution, hanged until they were dead, their heads to be severed from their bodies, and the bodied divided into quarters which were then to be at the disposal of Her Majesty the Queen. Three weeks later these sentences were commuted to transportation for life and on the 30th of June 1840 they were shipped off to Tasmania. Although they were pardoned in 1854 only John Frost returned to this Country. John Frost returned just in time to see the decline of the iron-making industry and with it the movement of industrial emphasis from iron to coal, from the northern outcrop towns to the new boom towns such as Abertillery. In 1856 Henry Bessemer discovered a way to convert iron to steel relatively cheaply and brought to an end the ‘glory’ days of the old Iron Works of our area. There was a reticence amongst some owners to invest in the new method, and the companies who failed to do so soon closed. The record of 970,727 tons of iron made in south Wales from 164 furnaces in 1857 was never to be repeated. In the 1870’s the trade of iron rails to the USA ceased, followed by a vast reduction in the home market as the new railway lines were being completed or being converted to steel rails. In the 1880’s the shipbuilders converted to steel and another market was lost. Coupled with this the South Wales ores contained a high amount of phosphorus and were unsuitable for steelmaking. This necessitated the importation of foreign ores, which in itself made sense to move the works nearer to the coastline. There had always been a small amount of foreign ore used, in the 1850’s there were around 240,637 tons of ore imported to an annual use of one million tons of local ore. By 1900 there were 1,300,000 tons of ore imported from Spain alone, with more coming from Sweden, Norway, Russia, Greece and Algiers. The total import of foreign ores in 1903 was; through Cardiff Docks, 804,000 tons, through Newport Docks, 346,000 tons, through Swansea Docks, 196,000 tons. By the beginning of the 20th Century, the decline was complete, the Dowlais Company had moved to Cardiff, and the others had shut down or now concentrated mainly on coal mining, all bar Ebbw Vale.

The Tredegar Works were re-organised in 1873 and renamed the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company, this new company abandoned steel production on a large scale retaining the mills for their own use and concentrated on coal mining. In 1882 the Works rolled its first steel rails, but in 1901 all steel production ceased. The Beaufort Works closed in November 1873, the Nantyglo Works closed in March 1874, and the Blaina Works converted to tin production in 1889.

Early coal and ironstone mining in the County simply consisted of scraping off the topsoil and removing the ores, they then resorted to building dams near the top of hills until a certain amount of water had been amassed, this was then allowed to flood down the hill and by doing so removed all the topsoil to expose both the coal and ironstone veins. This method was known as ‘Racing’ in English or ‘Rassa’ in Welsh and is how Rassau just to the north of Ebbw Vale obtained its name. As these outcrop workings became exhausted or insufficient for the demands of the Works it became necessary to dig deeper into the ground. Firstly levels (slants, drifts, adits) were opened up following the coal seams as they went deeper and deeper into the earth. These levels could only go so far as then ventilation and flooding difficulties made them impossible to work. Shallow pits were then sunk, probably well over one hundred between Tredegar and Brynmawr using the water balance method of winding. This system worked by filling a container of water that was fixed under the carriage on the surface of the mine, the operator would then release a brake and the combined weight of the carriage and the water would be sufficient to raise the carriage full of coal from pit bottom to the surface. Once the empty carriage had reached the pit bottom the water was drained off, and either run off through a drainage tunnel or pumped up back to the surface and the process repeated. This system of coal winding continued until the 1870s when it was replaced by steam winding, although the last one worked up until 1904. The water balance gear from the Brynpwllog Pit, which was between Rhymney and Tredegar is at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. The first pit sunk in the Tredegar area it was the Dukes Pit, which was 100 feet deep and sunk in 1806. In all the old Tredegar Iron Company sunk a series of pits numbered from No.1 (Bryn Bach) to the last of the series the No.12 (David Jervis’) which was sunk in 1840. When the No.7 (Mountain) pit was sunk in 1840 to a depth of 630 feet, it was the deepest water balance pit in the country, and therefore probably in the World. There were others such as the Ash Tree Pit, Water Wheel Pit, and Upper Ty Trist which was sunk in 1841. None of these pits reached the 20th century most of them being filled in 1897. In greater abundance were the levels which ranged from Cwm Rhos which was driven c1802, and on through Jack Edwards’, Nant-y-Bwch, Forge, Hard, Shop, Tramroad, and many more. The output of coal from these levels was so prolific that by 1818 it exceeded the needs of the Tredegar Works. In the Sirhowy area, the pits ranged from the No.1 or Company Pit to the No.9 or Mathusalem Jones’ Pit, as well as Richard Lewis’ Pit and the Engine Pit which was sunk in 1830 to a depth of 107 yards and later became the first pit in south Wales to use steam to wind coal. All the rest were water balance pits and were sunk around the 1840 mark to feed the Sirhowy Iron Works. They ranged between 35 yards (No.3) to 63 yards (No.1) in depth. The only one of these pits to work into the 20th Century was the No.9 or First Class Pit which later became Graham’s Navigation Colliery until closure in 1924.

Most of these early mines were opened and worked on the Contractor System this meant that an agreement was made between the iron masters and a small group of miners to work the coal and/or, ironstone in a particular area. The owners would provide the capital and lease out the mine and the contractors had to find the equipment and manpower to work it. They would then agree to produce a stipulated amount of coal/ironstone at a fixed price to be delivered to the ironworks. Payment for this work would be made quarterly.

By the mid-18th Century, the demand for coal was rocketing; steamships were becoming popular and needed coal for their boilers, as did the locomotives of the newly expanding railway system of the U.K. In 1850 the last tax (20 pence per ton) on exported coal was repealed, and new markets appeared from all over the World. In 1851 a Royal Navy report recommended Welsh steam coals to the Navy and another huge market opened up. In 1809 there had been 210,000 tons of coal exported through Newport Docks, a figure that only marginally increased to 256,795 tons of coal in 1823. Yet in 1830 Newport was only beaten by the Tyne and Wear ports in terms of coal exports. In 1847 this figure had increased to 617,177 tons of coal. Exports continued to rise dramatically to 3,495,795 tons in 1888 and to a peak of 5,928,060 tons of coal exported through Newport Docks in 1913. By this time the South Wales Coalfield was the premier coal exporter in the World, and the Bristol Channel was the busiest waterway in the World. It seemed that everyone wanted South Wales coal. The Tredegar Iron and Coal Company and the Ebbw Vale Steel, Iron and Coal Company were quick to adapt to the new markets, albeit in different ways, while the other iron companies of the northern outcrop within the Borough faded away into obscurity or remained small concerns.

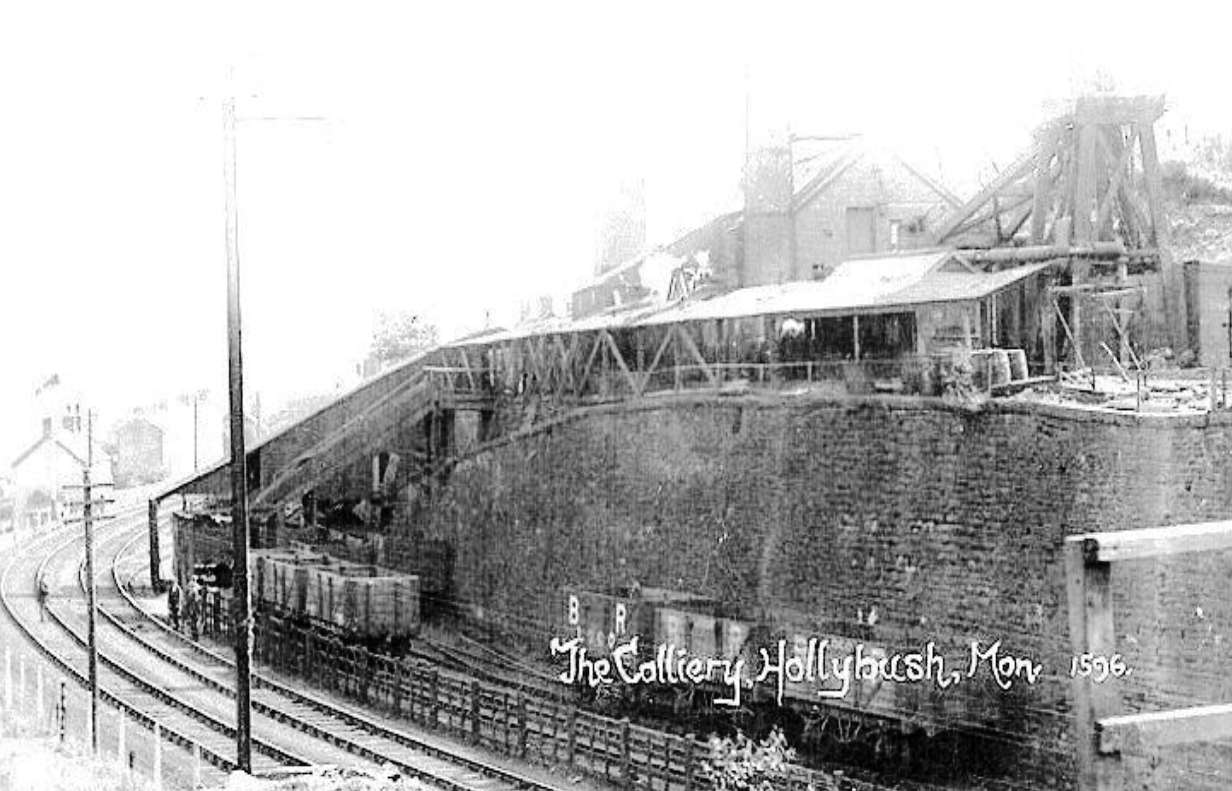

The Tredegar Iron Company was turned into the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company in 1873 and concentrated on coal mining as its main business. Unlike the Ebbw Vale it remained in its own valley (with the exception of McLaren Colliery in the Rhymney Valley) and adopted a more cautionary way of expansion. An interesting trait of this company was that it named most of its sinkings after the directors of the company, viz, Markham, Wyllie, Pochin, McLaren and Whitworth. The first major sinking of the new company was still in the Tredegar area at Whitworth Colliery which first produced coal in 1876 this was closely followed by Pochin Colliery a little further down the Sirhowy Valley. Coal production had reached 745,445 tons annually by 1885 and rose to 898,493 tons of coal in 1895. McLaren Colliery was then sunk in 1897 and linked to Bedwellty Colliery. In 1903 this company controlled the mineral rights of 4,600 acres, mostly in the Tredegar area but after one hundred years of intensive mining, all the best seams had been exhausted. In 1906 the TIC acquired the mineral rights to Lord Tredegar’s lands further down the valley between Hollybush and Ynysddu and opened up major collieries and model villages at Wyllie, Markham and Oakdale. Wyllie Colliery was the last deep mine to have been sunk in Monmouthshire it first produced coal in 1926. In 1923 the company employed 11,745 men producing 2,947,328 tons of coal, with a wage bill of £1,544,683.00. The trade depressions of the late 1920s and early 1930s affected the company and by 1935 production of coal was down to 1,900,000 tons with manpower being halved to 5,900 men. Prior to Nationalisation matters had improved slightly for the company with coal production in 1945 standing at 2,343,000 tons with 6,524 men employed but by now mostly outside of Tredegar in the collieries to the south of the Sirhowy Valley. There was now only one major colliery working in the Tredegar/ Sirhowy area – Ty Trist with a little to the south of the Town, Bedwellty Pits and then Pochin Colliery.

The Tredegar Iron Company was turned into the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company in 1873 and concentrated on coal mining as its main business. Unlike the Ebbw Vale it remained in its own valley (with the exception of McLaren Colliery in the Rhymney Valley) and adopted a more cautionary way of expansion. An interesting trait of this company was that it named most of its sinkings after the directors of the company, viz, Markham, Wyllie, Pochin, McLaren and Whitworth. The first major sinking of the new company was still in the Tredegar area at Whitworth Colliery which first produced coal in 1876 this was closely followed by Pochin Colliery a little further down the Sirhowy Valley. Coal production had reached 745,445 tons annually by 1885 and rose to 898,493 tons of coal in 1895. McLaren Colliery was then sunk in 1897 and linked to Bedwellty Colliery. In 1903 this company controlled the mineral rights of 4,600 acres, mostly in the Tredegar area but after one hundred years of intensive mining, all the best seams had been exhausted. In 1906 the TIC acquired the mineral rights to Lord Tredegar’s lands further down the valley between Hollybush and Ynysddu and opened up major collieries and model villages at Wyllie, Markham and Oakdale. Wyllie Colliery was the last deep mine to have been sunk in Monmouthshire it first produced coal in 1926. In 1923 the company employed 11,745 men producing 2,947,328 tons of coal, with a wage bill of £1,544,683.00. The trade depressions of the late 1920s and early 1930s affected the company and by 1935 production of coal was down to 1,900,000 tons with manpower being halved to 5,900 men. Prior to Nationalisation matters had improved slightly for the company with coal production in 1945 standing at 2,343,000 tons with 6,524 men employed but by now mostly outside of Tredegar in the collieries to the south of the Sirhowy Valley. There was now only one major colliery working in the Tredegar/ Sirhowy area – Ty Trist with a little to the south of the Town, Bedwellty Pits and then Pochin Colliery.

Following the collapse of the Chartist Movement in the late 1840s a gradual pick-up in trade quietened things down for a while, times were still tough, and living conditions were still primitive. The owners of the mines and works still controlled the area and still treated the workers with contempt as can be shown in 1857 when a miner was killed at the Pantyfforest Colliery at Beaufort. The Mines Inspectorate prosecuted the owners but the magistrates dismissed the case. Three of the magistrates were mine owners and the other one was a clergyman. In the 1870s the iron works were closing and their owners were looking for new ways of making a profit, as the vast majority were already owners of coal mines they now turned their coal production into the highly competitive coal export market, prime examples of this were the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company, and the Ebbw Vale Steel, Iron and Coal Company. The recent boom in the iron industry had forced the colliery owners to pay relatively high wages to compete with the wages of the Iron Works. They now had to cut costs in the face of this new competition they also had to contend with new legislation which permitted labour to organise itself. In February of 1871, the owners demanded a 10% reduction in wages, the main representative of the South Wales miners at that time, the Amalgamated Association of Miners, countered with a demand for a 10% increase in wages. The result was a twelve-week-long strike that gave only a slight increase in wages. In January of 1872, the owners demanded yet again a cut in wages of 10%, this time the proposed strike rapidly collapsed, and the men accepted the owner’s terms. In 1874 the price of coal fell from 22/- (£1.10) per ton to 12/- (60p) per ton and the owners again asked for a 10% reduction in wages which then would be brought down to 4/4d (22p) per day. On the 1st of January 1875, the miners withdrew their labour and started a five month period of strikes and lock-outs. In April the owners increased the demand for a reduction in wages to 15% and on the 31st of May 1875, the miners went back to work with a 12.5% reduction in wages. During this period there was no united trades union movement in the Coalfield, the largest union, the Amalgamated Association of Miners went bankrupt following the 1875 strike, at that time it had 42,161 members in the Coalfield. In the Blaenau Gwent area, the trade union movement was fragmented with numerous small unions in operation; the Ebbw Vale and Sirhowy Colliery Workmen had 3,500 members, the Monmouthshire and South Wales District Miners had 6,059 members throughout south Wales, the Hauliers and Wage men of South Wales and Monmouthshire had 5,500 members, while the Monmouthshire Western Valley Miners had 500 members. Thomas Richards of Tredegar who was to become the first General Secretary of the South Wales Miners Federation formed the Ebbw Vale Miners Association in 1884. Following this four year period of disruption, it was then agreed that wages should be regulated by a sliding scale according to the selling price of coal. With some amendments, this system continued in practice until the Conciliation Board was formed in 1902. During its first four years of operation wages were firstly reduced by 7.5% and then by 10% it wasn’t until 1882 that wages reached the levels enjoyed in 1869. The agreement was revised in 1890, and wages rose by 57%of the standard by mid 1891which prompted the owners to give notice to lower the rate from 10% to 8.75%, wages then tumbled, rose, and fell back down again. This system was now despised by the workmen with its bias towards the owners so that they did not have to give a rise in pay until three months after a rise in the price of coal but could immediately cut wages if there was a reduction in the price of coal. In September 1897 the miners went out on strike for a 10% pay rise but were defeated and it wasn’t until 1902 that the Sliding Scale Agreement was finally abolished.

While all this was going on in 1893 the British Colliery Owners called for a 10% reduction in wages, as south Wales was tied to the Sliding Scale Agreement it continued to work through the fifteen-week strike between August and November. The Miners Federation of Great Britain then tried to close down the Coalfield by a strike of hauliers. These hauliers marched from pit to pit in an attempt to close them down, this led to pitched battles between the opposing factions and resulted in the military being called in, on the 12th of August 1893 a mob of 4,000 strikers attacked the Graig Fawr and Victoria collieries resulting in the 2nd Devonshire Regiment being billeted at Ebbw Vale and Blaenavon. On the 17th of August, 2,000 working miners fought the strikers on the hillsides above Ebbw Vale and put them to flight. The workmen suffered another defeat in 1898, and this was enough to bring the seven district unions now in South Wales together to form the South Wales Miners Federation, this Union continued to represent the miners of South Wales until 1945 when its members voted to become the South Wales Area of the National Union of Mineworkers. It started off with 60,000 members rising to a peak of 197,668 members in 1920, the troubles of the 1920s seriously affected membership and it dropped to 72,981 in 1927. In 1940 it had climbed back to 120,575 members, and in 1942 it became the first union on the UK to obtain a closed shop with every working miner becoming a member.

In the peak period for production in the Coalfield, 1913, the Tredegar Valley District had 8,253 members in 12 Lodges. In 1912 there was yet another strike, this time for a minimum wage of four shillings and sixpence a day, not an exorbitant request considering that the miners in the area worked an average of 54 hours 52 minutes underground each week producing an average of 310 tons of coal a year, the death rate was 1.86 men per 1,000 men working.

Despite all these disputes, this was the boom time for the South Wales Coalfield, and none benefited more than the Landlords. The town of Tredegar didn’t exist until the founding of the Iron Works in 1800 it was then named after the home of the local landlord Sir Charles Morgan. The Morgan family dominated the social and political life of the area, the family continuously holding a Parliamentary Seat for 250 years until they were finally ousted in 1906. Llewellyn ap Morgan had supported the Glyndwr revolt in 1402 and as a result lost his home, this and a larger estate was recovered by Sir John ap Morgan when he supported Henry VII’s claim to the throne, he also became sheriff for the area. Throughout the ages, they continued to build up their estates most of it purchased from the Earl of Pembroke. Amongst the colourful ancestors of this family is Thomas Morgan who acted as an agent to Mary Queen of Scots, it was an intercepted letter from Morgan that resulted in Mary’s execution. Sir Henry Morgan was a one-time pirate and Governor of Jamaica. Sir Charles Morgan was born in 1760, was an MP for 49 years, was captured at Yorktown during the American War of Independence and was the grandfather of the first Lord Tredegar. Captain the Hon. Godfrey Morgan (later Viscount Tredegar) took part in the Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimea War, his charger Sir Briggs is buried in the gardens of Tredegar House at Newport and has its own headstone. He was born in 1831 and died in 1913. In 1912 it was estimated that the estate was receiving £1,000 a day in coal royalties. He was replaced by his nephew, Courtney Charles Morgan, Lord Tredegar, who was forced to cut the running costs of his estates, increase rents and sell of the Breconshire part of his holdings in an attempt to balance his books. During a Parliamentary Investigation held into mineral royalties in 1919, he gave evidence stating that his estates ” in which there are minerals in situate in the Counties of Monmouth, Glamorgan and Brecon, the approximate area of my estates in the above three counties is 32,000 acres in Monmouthshire, 7,000 acres in Glamorganshire, and 43,000 acres in Breconshire, most of this consists of waste or common lands of the Lordship of Brecon. Of these areas only about 12,500 acres in Monmouthshire, 2,500 acres in Glamorganshire and 3,800 acres in Breconshire contain coal. The average annual income received by me in respect of royalties and dead rents on coal for the six years ending December 1918 was 3,564,500 tons with an average royalty in that period of one-thousandth of a penny less than five pence per Imperial Ton. Questions have been asked about my Tredegar Park Railway (known as the Golden Mile) “He then went on to say that he received £19,000 per year from tolls on this railway – it had cost £40,000 to construct. Sir Robert Salisbury owned property just to the south of Tredegar and received £30,000 to £40,000 per year in mining royalties. He became so rich that he opened his own bank in Newport and built Llanwern Mansion. The land around Ebbw Vale was owned by the Beaufort Family of Badminton fame. This family originated from William Herbert who had supported Henry VII and went on to become the Worcester’s and then the Beaufort’s. Along with the Morgan’s they controlled the political life of Monmouthshire and for 250 years of the two MP’s for Monmouthshire were a Morgan and the other a Beaufort. In 1918 the County was divided into six seats including Abertillery and Ebbw Vale, but it was at Pontypool that Labour won its first Parliamentary seat, and it wasn’t until 1919 that the Labour Party won a majority on the Monmouthshire County Council.

In 1915 during the First World War, the Runciman Award gave the miners six shifts for working five but it excluded many surface workers such as the stokers, and yet again the miners of Llanhilleth, Six Bells, Cwmtillery, Roseheyworth and Tillery came out on strike until this payment was made to all mine workers. In February of 1921 another World wide trade depression affected the Coalfield particularly badly with 80,000 miners being laid off. The miners were still under state control following the war and as a result, were enjoying the highest wages in their history at 21 shillings 6.75 pence per shift. Government control ended in March and the owners announced that there would be a drastic cut in wages. On Friday the 1st of April 1921 over one million miners were locked out of their workplaces until they agreed to the new terms. Troops were again sent into the Coalfield, with 250 naval ratings being based at Abertillery. The Miners Federation of Great Britain accepted the owner’s terms in June although the miners in South Wales were still opposed to them. By October of that year, the miners wages had dropped to around half of what they were to nine shillings and five and a half pence per shift. Trade depressions were now becoming all too familiar to the hard-pressed miners. It was the same old story in 1926 when yet again the owners demanded a cut in wages, plus an increase in the hours worked. On the 30th of April 1926, the notices expired, with on the 4th of May a General Strike of all the workers in the UK being called in support of the miners, this collapsed after one week leaving the miners to fight on alone. The strike was fairly quiet within the area until the last eight weeks when there were eighteen major clashes between the strikers and police protecting the working miners. On the 29th of November 1926, a ballot of all the miners in the UK accepted the owner’s terms and the men returned to work on the First of December 1926. This reduction in wages and increase in working hours did little to restore the fortunes of British industry, and as we entered the 1930’s we entered a time of utter despair and grinding poverty for the Tredegar and for south Wales. Newport Docks had exported 6,769,493 tons of coal in 1923 but by 1936 this had dropped to2,555,713 tons of coal, and by 1947 total exports for the whole of the Coalfield came to 1,210,000 tons of coal. More than any other area of the UK the South Wales Coalfield depended on the export trade, the first decline in this trade was in 1921, there was a revival in 1923 due to a strike of miners in the USA, but the times were changing, oil was rapidly replacing coal in the ships and railways of the World, the Versailles Reparation Treaty replaced some markets with German coal, and other European nations such as Poland were subsidising the coal exports in order to gain currency. On top of this, the USA was replacing Wales in the South American markets, and in 1925 the British Government returned to the Gold Standard which made exports dearer. The result of all this was that the price of South Wales coal dropped from 36/6d per ton in 1921 to 22/6d in 1925, the proceeds from exports also dropped during this time from £50 million to £37 million. Unemployment in Tredegar was 34.2% of the working population in 1932 as the pits began to close through lack of demand for coal, and if you thought that was bad, by 1934 the unemployment level for Blaina was 80%, and in Abertillery it was 85%, with the Monmouthshire County Council’s Health Department stating that 80% of the children in the area were “physically incapacitated in one degree or another and that only 10% were in normal health.” For the whole of Monmouthshire part of the Coalfield in 1931 there were 8,988 workers unemployed out of a total workforce of 39,253, in 1932 the unemployed figure had almost doubled to 16,252 while the total workforce had dropped to 37,031. The total workforce continued to drop, it was 35,410 in 1934 and 33,974 in 1935, but by 1935 the worst was over and the unemployed figure had also dropped to 9,313. Between April 1931 and June 1933, 10,191 people 2.5% of the population left Monmouthshire to seek work elsewhere, followed by another 2.75% during the next two years. The poor law system at Tredegar collapsed under its debts and had to be rescued by the Government. The whole of this area was categorised as a distressed area and was only saved economically by the threat of, and the outbreak of the Second World War. The Second World War was over, the Nation now had to face up to a new challenge – that of recovery. The Great War leader Winstone Churchill lost the general election to Clement Atlee’s Labour Party and its promises of a welfare state, National Health Service and the nationalisation of the coal mines, steel works and railways. Amazingly this Government fulfilled its promises and the Nation’s mines were Nationalised and brought under National Coal Board control in 1947. (The only exceptions were the very small mines employing less than twelve men underground).

This Nationalisation of the Nation’s coal mines had a long history, as early as 1884 miners’ leaders had advocated it, and in 1893 the TUC accepted nationalisation as part of its policy. During the 1914 – 18 War the South Wales Miners came out on strike for wage increases, when another strike seemed possible in 1916 the Government took control of the South Wales Coalfield. This was followed in 1917 by the Government taking over the whole of the industry until 1921. In 1942 the Government again assumed operational control of the coal mines. The Coal Industry Nationalisation Bill was introduced to Parliament in 1945, it passed into Law in 1946 and on the First of January 1947, the NCB took control of the industry on the nation’s behalf. Overnight it became the Nation’s biggest single employer of labour with almost 800,000 workers, 110,000 of these working in the South Wales Coalfield. South Wales came under the control of the South Western District which was one of nine Divisions. The first Divisional Director was Lieutenant General Sir A. Goodwin-Austen. He controlled almost 220 collieries and more than 100 licensed mines in south Wales, the Forest of Dean, Bristol and Somerset. The thirteen collieries of Blaenau Gwent were part of the No.6 (Monmouthshire) Area with its Area General Manager, H. McVicar based at Abercarn. The export markets, the very lifeblood of the Coalfield had virtually disappeared, but new markets were now replacing them and coal was urgently needed to re-establish British industry and to combat the bitterly cold winters of the late 1940s. The industry now accounted for 21% of South Wales Coal production followed by electricity generation which accounted for 19% of production, domestic demand stood at 14% of the total, coking coals accounted for 12%, the railways now only accounted for 10% of production, others 10%, gas manufacture 3%, and internal use and the miners and widows concessionary coal accounted for the other 11%. Locally the Ebbw Vale Steel Works had been reopened in 1939 with Government help by Richard Thomas & Company with a new hot strip and cold reduction plant that was the first continuous wide strip mill outside of the USA. In 1946, 107,625 South Wales miners produced 20,950,000 tons of coal but by 1950 following NCB’s investment into the mines 102,000 miners produced 24,314,000 tons of coal, giving a profit of £1 for every ton of coal produced. The miners themselves were also benefiting, in 1938 the average wage per shift in the South Wales Coalfield was 10 shillings and 11 pence (60p) by 1952 this had risen to 38 shillings and 4 pence (£1.91) per shift. The closure of Ty Trist Colliery in 1959 was the end of coal mining in the Tredegar Town area with only Pochin Colliery left to mine the northern Sirhowy Valley. Then came the massive closure programme of the 1960’s to comply with the reduction in the demand for coal which resulted in the closure of Pochin Colliery in 1964 and the end of deep mining in Tredegar.

THE TREDEGAR IRON AND COAL COMPANY

The original Tredegar Iron Company was formed in 1799 by Samuel Homfray, Richard Fothergill and Matthew Monkhouse with a lease from Sir Charles Morgan for 3,000 acres to run over 99 years at a rental of two shillings and sixpence per acre per year. Their earliest coal workings were levels driven into the outcropping seams, with the first pit, Dukes Pit, being sunk in 1806. Their second pit was the No.1 or Bryn Bach which was sunk in 1818 and was followed by the No.2 Pit in 1820. When the No.7 or Mountain Pit was sunk in 1841 to a depth of 630 feet it became the deepest water balance pit in the world. The Tredegar Iron Company went on to sink a total of at least twelve pits and scores of levels.

The Tredegar Iron and Coal Company was formed in 1873 out of the old Tredegar Iron Company by Isaac Lowthian Bell, William Menelaus, Henry Davis Pochin, William Newmarch, Sidney Carr Glyn, Benjamin Whitworth and Edward Williams, who were later joined by James Wyllie and Charles Markham. The new company then concentrated on coal production reducing iron, and later steel making for their own use. The last steel made at Tredegar was in 1901. An interesting trait of the new company was to name its sinkings after its directors, i.e., Whitworth, Pochin, Markham, Wyllie and McLaren, the major exception was Oakdale Navigation. The first major sinking of the T.I.C. was Whitworth Colliery which first produced coal in 1876, this was closely followed by Pochin Colliery where sinking started in 1876. By 1878 the company operated: Ash Tree, Bedwellty pits, Bedwellty levels, Darran levels, Tredegar pits Nos. 1,3,6,7 & 8, Patches, Ty Trist, and Whitworth pit and drift. Coal production had reached 745,445 tons in 1885 increasing further to 898,493 tons by 1895. In 1896 the company operated; the Bedwellty levels, Bedwellty Pits, Pochin, Ty Trist, Whitworth Drift and Whitworth Pits employing 3,092 men. McLaren Colliery was sunk in 1897 and was the only Tredegar Iron and Coal Company pit to operate outside of the Sirhowy Valley. In 1903 the company controlled the mineral rights to 4,600 acres, but by this time most of the workings in the Tredegar area were becoming exhausted and in 1906 the company acquired the mineral rights for Lord Tredegar’s lands further down the valley between Hollybush and Ynysddu. Subsidiary companies were formed to control the new sinkings, with the Oakdale Navigation Colliery Company operating Oakdale Navigation and Waterloo which first produced coal in 1912.

The Markham Coal Company sunk Markham’s Navigation in 1913, and it was originally intended for the Tredegar (Southern) Collieries Limited to sink a third colliery at Gelligroes around the same time, but a combination of severe flooding during the sinking and the First World War delayed this until the Wyllie Colliery was sunk in 1925 at a new site. Wylie was the last deep mine to be sunk in Monmouthshire. In the three cases, the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company built ‘model’ villages to accommodate the workers of the new pits. During the period between 1873 and 1923 annual output of the company’s pits increased from 600,000 tons of coal to 2,947,328 tons, with in 1923 the company employing 11,745 men with an annual wage bill of £1,544,683. 8,000 tons of coal a week from the company was exported through Newport Docks. The depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s affected the company badly and by 1935 output was down to 1,900,000 tons and manpower halved to 5,900. The Board of Directors at that time consisted of; Chairman, The Rt.Hon. Lord Aberconway. Directors, Colonel Sir Edward Johnson-Ferguson, Evan Williams, N.J. McNeil, W.D. Woolley (General Manager), H.O. Monkley, Secretary. The headquarters of the company was at Fenchurch Street in London and the company ran the following pits; Ty Trist, Bedwellty, Pochin, McLaren, Wylie, Oakdale, Waterloo and Markham. By 1945 matters had improved somewhat and annual output stood at 2,343,000 tons of coal with 6,524 men employed.

Along with the Nation’s other major colliery concerns, the mining interests of the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company were Nationalised in 1947 and came under the control of the National Coal Board. On Nationalisation the Board of Directors consisted of; Lord, the Rt. Hon. P.C. Aberconway of Bodnant, North Wales who was chairman, W.D. Woolley of Tredegar who was Deputy Chairman and Managing Director, Daniel Morgan who was the General Manager and a board of Col. Sir Johnson-Ferguson of Dumfriesshire, Charles M McLaren of London and Sir Holberry Mensforth of Hazlemere, Bucks. Pochin Colliery employed 739 men working underground and 167 men on the surface while Ty Trist employed 428 men working underground and 139 on the surface.

In June 1953 an extraordinary meeting of the shareholders of this company agreed to winding up the company voluntarily appointing Mr. Alexander Grieve as the liquidator. The company’s subsidiaries were also liquidated.

Henry Davis Pochin was born in Leicestershire in 1824 and became an industrial chemist. In the mid 1860s along with other Manchester businessmen, he formed various companies involved in coal, iron and steel. He was also elected MP for Stafford in 1868. Pochin Colliery was named in honour of his daughter, Laura who married Charles McLaren who became Lord Aberconway. He died in 1895.

Charles Benjamin Bright Mclaren was born in Edinburgh in May 1850 and was educated at Heidelberg, Bonn and Edinburgh Universities. In 1877 he married Henry Pochin’s daughter Laura, and they had four children. He later became a lawyer and a politician. In 1902 he became Sir Charles McLaren, Baronet of Bodnant and in 1911 he was made Baron Aberconway. Following the death of his father-in-law (Pochin above) he became heavily involved in the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company becoming chairman. He died in January 1934 with his son Henry becoming the Second Baron and chairman of the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company. He died in 1959.

Information supplied by Ray Lawrence and used here with his permission.

Return to previous page