Pontypridd, Taff Vale.

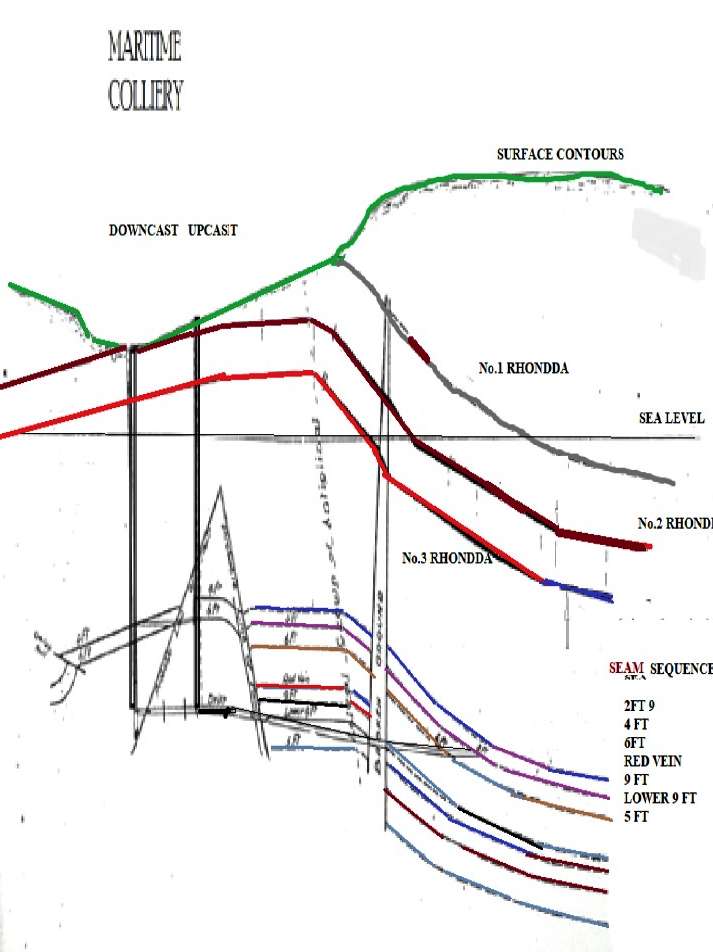

This pit, which has also been called Marine Rhondda and Rhondda Junction, was sunk by John Edmunds in 1837 to the No.3 Rhondda seam which it found at a depth of 60 yards. Originally winding was done by the water balance method. This was the common method of winding in the shallow pits of the early nineteenth century. Probably over 100 pits near the rim of the Coalfield worked this method, The system was worked by filling a container of water that was fixed under the carriage with the empty tram in it on the surface. The container under the carriage on the pit bottom with the full tram in it was left empty. The operator would then release a brake and the combined weight of the water, carriage and tram would be sufficient to raise the full tram of coal from the pit bottom to the surface. Once the empty tram had reached pit bottom the water was drained off, and either ran out through a drainage adit or pumped back to the surface. Another empty tram would replace the full one on the surface and the process repeated. Ponds were constructed at the surface of the mine to feed the tanks. This system was popular in south Wales until the 1870s when steam winding rendered it outmoded. It was not until the 1860s that the use of steam winding came into general use in the South Wales Coalfield.

This pit, which has also been called Marine Rhondda and Rhondda Junction, was sunk by John Edmunds in 1837 to the No.3 Rhondda seam which it found at a depth of 60 yards. Originally winding was done by the water balance method. This was the common method of winding in the shallow pits of the early nineteenth century. Probably over 100 pits near the rim of the Coalfield worked this method, The system was worked by filling a container of water that was fixed under the carriage with the empty tram in it on the surface. The container under the carriage on the pit bottom with the full tram in it was left empty. The operator would then release a brake and the combined weight of the water, carriage and tram would be sufficient to raise the full tram of coal from the pit bottom to the surface. Once the empty tram had reached pit bottom the water was drained off, and either ran out through a drainage adit or pumped back to the surface. Another empty tram would replace the full one on the surface and the process repeated. Ponds were constructed at the surface of the mine to feed the tanks. This system was popular in south Wales until the 1870s when steam winding rendered it outmoded. It was not until the 1860s that the use of steam winding came into general use in the South Wales Coalfield.

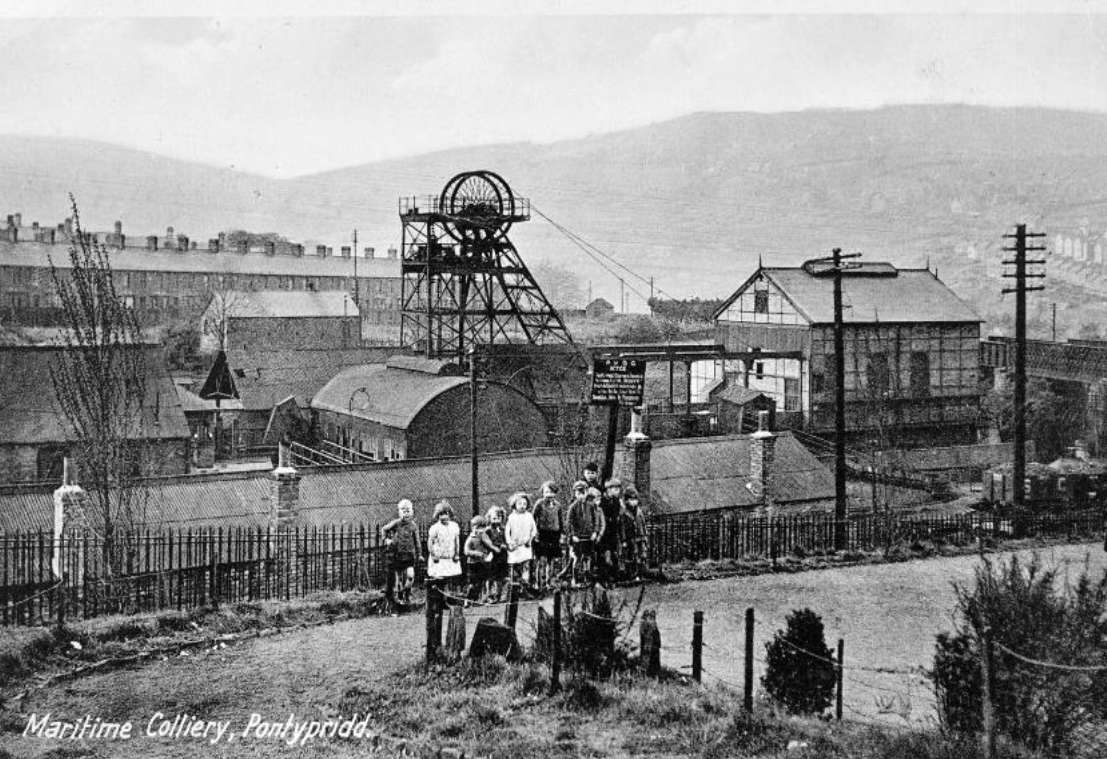

Maritime Colliery was served by the Taff Vale Railway and it had a sidings capacity of, 74 full wagons, 204 empty wagons, and 91 other wagons.

In January 1879, Pontypridd Magistrates heard that the manager of the colliery had allowed gunpowder to be used at the mine within three months of gas being found there which was in contravention of the Coal Mines Regulations. The manager was fined £10, and the fireman £3.

In August 1882 the Weekly Mail reported that the Crawshay Brothers were interested in the colliery. The newspaper continued to state that the colliery was on one of the finest mineral takes in the Rhondda Valleys and the known seams were the Nos.1,2, & 3 Rhondda’s. Abergorky, Two-Feet-Nine, Four-Feet, Six-Feet, Yard, Nine-Feet, Dirty Vein, Gadlys and Lower-Four-Feet. The present company had secured the coal under the following farms; Gelliwion (housecoal only), Penrhiw, Llwynypia, Tirarlwydd and Pencoedcae, with a portion of the takings from Coedcaedu, Penbwch and Gellidraw farms.

The colliery continued to explain that a great fault ran down the Gellywion Valley and that there were two collieries, the Newbridge Rhondda and the Rhondda Junction. The Rhondda Junction Colliery was the lowest in the valley of the two, with the valley being split by the fault. It seems to have been sunk in the north-east corner of the fault and that is why results have been disappointing. The shaft was 284 yards deep.

In February 1883 they hit the Aberdare Lower Four-Feet seam which had a thickness of 6 feet 4 inches. To celebrate, the manager, Morgan Thomas, held a dinner at the Colliers Delight at Pontypridd for 120 workmen that went down a treat. What didn’t go down a treat was that in April 1886 the company sacked most of their older workmen, and on top of this ordered them to leave their homes which were owned by the company. This created a lot of ill feelings, not only with the Maritime workmen but throughout Pontypridd. However, the men to be sacked were not intimidated that easily and wore the notices on their hats. Without any comment from the owners it was assumed, and all those dismissed were Welsh, that the owners were trying to bring in cheaper ‘foreign’ workers.

In February 1883 they hit the Aberdare Lower Four-Feet seam which had a thickness of 6 feet 4 inches. To celebrate, the manager, Morgan Thomas, held a dinner at the Colliers Delight at Pontypridd for 120 workmen that went down a treat. What didn’t go down a treat was that in April 1886 the company sacked most of their older workmen, and on top of this ordered them to leave their homes which were owned by the company. This created a lot of ill feelings, not only with the Maritime workmen but throughout Pontypridd. However, the men to be sacked were not intimidated that easily and wore the notices on their hats. Without any comment from the owners it was assumed, and all those dismissed were Welsh, that the owners were trying to bring in cheaper ‘foreign’ workers.

In June 1888 an oil lamp at the top of the pit fell over and ignited some tram oil, the flames spread rapidly until the whole wooden covering of the pit top was on fire. Thousands of people joined in to try and put the fire out, but they could do little to stop the smoke going down the shaft and ruining the underground ventilation. The fan had to be stopped until the smoke cleared. The local authority and police soon brought the fire under control with the aid of the Cardiff Fire Brigade. The 55 men underground were brought up safely some hours later. The fire occurred on the Thursday and work resumed on the following Monday.

In the Colliery Guardian dated the 17th May 1889 an advert asked for tenders:

For deepening two shafts at Pontypridd about 100 yards and 60 yards respectively for the Maritime Coal Company Limited, Pontypridd.

In September 1892 the pit was shut down suddenly without giving the men their required one month’s notice, or paying them their outstanding wages. In November 1892 things started to brighten up for the men who had been employed at the colliery prior to its closure. Rumours abounded that a new company was being formed to run it, this seemed to be backed up by horses being taken back down and underground repairs being carried out. During this period the men were in near destitution, depending upon relief payments where they qualified, and donations from other miners, for example, in that week the Plasycoed (Pontypool) Colliery workmen donated £5, as did the Tylorstown and Standard Colliery workmen, the Wattstown Colliery workmen donated £10 and Mr. Ignatius Williams of Pontypridd gave £3.3s. On the 24th of March 1893, a winding-up order was issued for the Maritime Coal Company. It didn’t last for long though, the leaseholders of the pit, the Rhondda Junction Welsh Coal Company, issued notices to the officials and men that their services would not be required after the one-month notice.

After a year of lying idle, in June 1894, Maritime was purchased by the Great Western Colliery Company. Due to the geologically faulted area around the shafts at Maritime the Great Western Company intended not to work the coal through Maritime but to extend the workings into the Maritime take which would be a bitter disappointment to the workmen hoping to seek employment there.

In 1893 a Waddle type ventilating fan was installed, it was 30 feet in diameter. Waddle fans were built by the Waddle Engineering and Fan Company Limited of Llanelli. The fans were most common in their local area of South Wales, but they were also widely used in other mining areas in England.

By January 1894 the old owners, the Rhondda Junction Company, were unable to find the money to pay the rates on the colliery at the end of their tenure, therefore the local authority called in the Official Receiver. The receiver reported that the company’s assets were covered by debentures and other mortgages, and the sale of the company’s property had not raised enough money to discharge its debts, therefore there was little likelihood of ordinary creditors being paid.

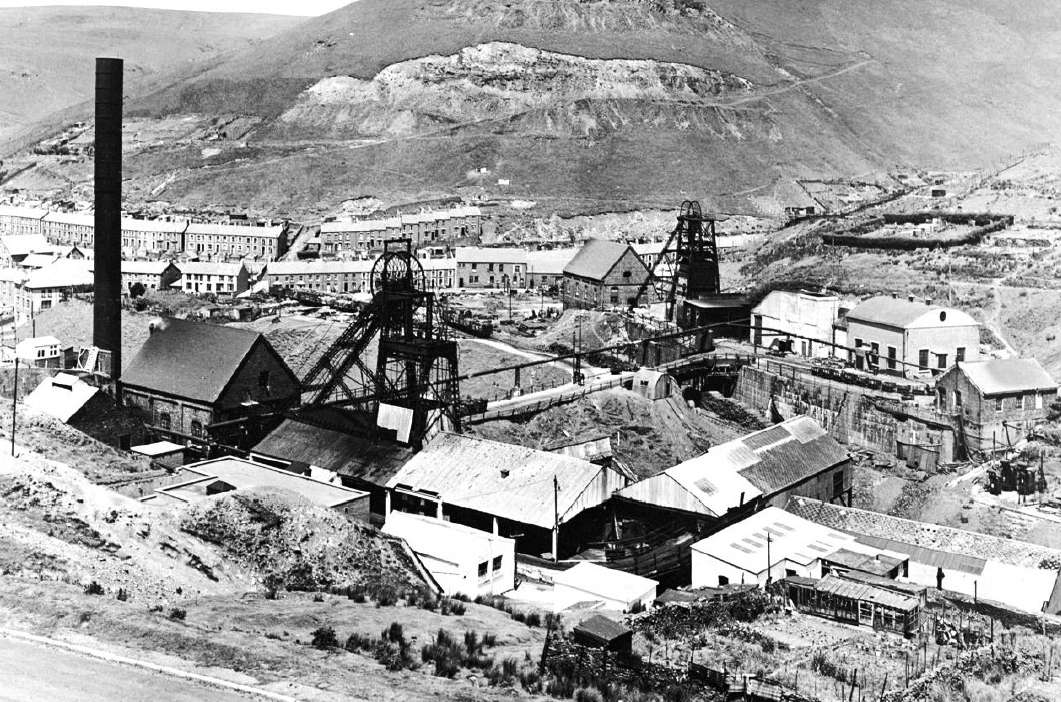

In 1896 the manager was W.M. Jones and by 1897 this colliery was again lying idle. In 1904 it was decided to deepen and enlarge the shafts to the steam coal seams of the Lower and Middle Coal Measures to a depth of 390 yards and expose an estimated 12,000,000 tons of coal. Work on the downcast shaft started on the 15th of October 1904 and it was deepened by 108 yards by the 15th of April 1905. The shaft was now 18 feet in diameter and had been completed at a rate of 4.4 yards per week. The work on the 12 foot diameter upcast shaft started on the 21st of November 1904 and following extensive repairs it was completed to a depth of 111 yards by the 3rd of June 1905, at a rate of 4 yards per week. A connecting drift between the two pits was made just above the Six-Feet seam in disturbed and faulted ground. Advance on the connection averaged 6.6 yards per week but was stopped altogether for eleven weeks waiting for a blower of gas to disperse. The link-up was made on the 18th of November 1905. The main drift into the coal was 18 feet wide at the floor, 15 feet wide at the roof and 10 feet six inches high. It was equipped with a double road endless rope haulage.

In the February 1906 report of the Great Western Company, they stated that Maritime Colliery had been stopped to enable the shafts to be deepened, and the winding shaft to be enlarged. They had reached the steam coal seams and were driving into them.

In 1908 the manager was W.J. Davies. In 1913 it was back in full production and employed 843 men. The manager was still W.J. Davies. He was still there in 1927. This company was a member of the Monmouthshire and South Wales Coal Owners Association. Maritime Colliery was the first pit in the South Wales Coalfield to have by-product coke ovens.

On the 6th of August 1920, there was a very lucky escape for Henry Salter an overman at Maritime, and for Robert Thomas a fireman. As the law demanded the workings had to be inspected before the men were allowed down. Messrs. Salter and Thomas were the ones designated to carry out this task. Unknown to them there had been a roof fall in the one district that had blocked the flow of air and allowed methane (firedamp) gas to accumulate. As they walked into the foul air they collapsed unconscious. When they failed to return at their normal time a search party was sent down the pit and found them just in time to save their lives. Another pre-shift inspection carried out by another overman, Thomas Evans, on the 10th of September 1924 resulted in him collapsing and dying.

Maritime Colliery came under Government control early in the First World War in an attempt to secure coal supplies to the armed forces, along with the rest of the Coalfield the colliers at Maritime earned the highest wages in their history during this time, but it wasn’t to last; In February of 1921 there was a world-wide trade recession which caused 80,000 miners to be laid off and to the surprise of everyone the government announced that it was bringing the date of de-controlling the mines forward to March 1921. The owners were back in control of the collieries again and on the 16th of March gave the men notice that they intended to end all contracts on the 31st of March, on the 1st of April all miners in the United Kingdom (1,100,000) were locked out of their workplaces until they accepted the owners reduced terms. The government declared a state of emergency and troops were moved into the coalfields. On the First of May 1921, the men returned to work defeated, and some would say betrayed by the leadership of the Miners Federation of Great Britain and by October of that year wages in the South Wales Coalfield had dropped to under half of what they were in February. The owners continued to push for more concessions from the miners, not only reducing wages but also extending working hours and abolishing long-established customs. There was a major concern at Pontypridd that men were illegally working the levels around Maritime and selling the coal to companies for £3 per ton. The unions were annoyed that none of this coal was given to the soup kitchens and wanted the practice stopped. The magistrates ordered the police to destroy the entrances to the workings. The union was also annoyed that the cost of the military and extra police around Pontypridd came to £8,000 a week, a sum that could be spent on the soup kitchens.

July 1921 was hot and sunny and Thomas Stanfield was broke, so he went around the café’s and shops of Pontypridd claiming that he was a policeman at Maritime Colliery who had lost his wallet. He obtained cigarettes and half a pound of pork from the Station Café, at Gazzi’s he borrowed 30 shillings, and at the Fox and Hounds, he borrowed £2. In all thirteen other similar offences were admitted. He received four months of hard labour.

On the 26th of May 1923, twenty bleary-eyed men stepped onto the cage for their 400 yard drop to pit bottom. Halfway down a guide rope unravelled and wrapped around the cage making it unmoveable. It took the whole shift to get those men back to safety. The 14th of November 1923 was the date of the inquest on the body of George Henry Vaughn aged 61 years. Mr. Vaughn was a pipe fitter at the Maritime Colliery and was repairing a pipe on an underground roadway when he fell under a journey of trams and was crushed to death. The man controlling the travel of the journey had failed to warn him that it was coming. David Jones was not so lucky on the 24th of July 1925 when a collapse of the roof in his workplace (stall) killed the 48 year old collier. A newspaper article in March 1924 highlighted the incompetence of the local council. Maritime’s coal solely supplied Pontypridd with its lighting and heating requirements, and although the colliery sold the coal at an equivalent of 9 pence per 1000 cubic feet, and the council sold it for 6 shillings per 1,000 cubic feet, the council still lost money on the deal.

In 1926 the colliery owners once again demanded concessions from the miners and on the 30th of April locked the miners out of their workplaces until they conceded to their demands. The Trades Union Council called a General Strike in support of the miners which started on the 4th of May, however for various reasons, most of them political, the strike collapsed on the 12th of May and the miners carried on alone, for eight weeks on and the strike remained solid in south Wales, apart from 20 men working at Taff Merthyr but on the 1st of December 1926 the men were forced by starvation back to work, that is the ones allowed back, most of the activists were black listed and it would be many, many years before they would find employment again. One man who was re-employed, Edwin Jones, aged 22 years, decided to seal another man’s wages. He was caught and on the 29th of September 1927 received two months of hard labour for his troubles. Indicative of those times and the hardening attitudes of the owners was that in October 1927 they refused to give the banksmen (the men at the top of the shaft who loaded/unloaded the trams and let on/off the men) any mealtime in an eight-hour shift.

On the First of April 1932, a 1,086 yard long tunnel was completed that linked this colliery to Cwm Colliery with Maritime’s coal being sent up the Cwm’s shafts. It was closed several times during the period 1930 to 1935 to due trade recessions but by 1935 employed 80 men on the surface and 640 men underground, with the manager being T. Powell. By this time the Great Western Colliery Company had come under the control of the Powell Duffryn Steam Coal Company Limited, who in April 1928 purchased all the shares of the Great Western Company which was then liquidated. This colliery had its own coal preparation plant, coke ovens ( a further six coke ovens were installed in 1934, and by product plant. In 1943 it was managed by H.M. Bradford and employed 325 men working underground in the Six-Feet and Five-Feet seams and 68 men working at the surface of the mine.

On Nationalisation in 1947 this colliery was placed in the National Coal Board’s, South Western Division’s, No.3 (Rhondda) Area, Group No.2, and at that time employed 66 men on the surface and 348 men underground working the Six-Feet, Nine-Feet and Upper-Five-Feet seams. The manager was still H.M. Bradford. The NCB reported that the colliery had two shafts; the downcast was 389 yards deep and 18 feet in diameter and used for men, materials and coal winding. The upcast ventilation shaft was 378 yards deep and 12 feet in diameter and used for ventilation only.

By 1954 the Upper-Five-Feet seam had been abandoned, and manpower stood at 82 men on the surface and 322 men underground. The manager was still Mr. Bradford. In 1955 out of the total colliery manpower of 338 men, 178 of them were working at the coalfaces, the coalface figure increased to 226 men in 1956, it was 220 men in 1957 and 187 men at the coalfaces in 1958. The coking plant was closed on the 20th of November 1957. In 1961 this colliery was still in the No.3 Area’s, No.2 Group along with Cwm and Coedely collieries. This Group had a total manpower of 2,922 men, while coal production for that year was 569,721 tons. The Group Manager was J.J. Lewis and the Area Manager was G. Blackmore.

The raising of coal was centralised at Cwm for the three pits with Britannic also planned to be brought into the scheme. Over 3,000 men were to be employed with output increasing from 4,500 tons per week to 6,500 tons per week. Two new roadways were driven from Maritime Colliery to Cwm Coedely to join the 1,000 yard roadway that was driven 20 years previous. The new washery and coke ovens at Cwm required a vast amount of water to operate so water was pumped out of two abandoned Rhondda mines and taken overland to Maritime where it was piped underground to Cwm and once again brought to the surface.

The 1950s continued to see a decline in the industry, partly due to the closure of uneconomic collieries, and partly due to the miners “voting with their feet” and seeking healthier, safer and better paid jobs in factories and elsewhere. In 1950, 102,000 miners produced 24,314,000 tons of coal in the Coalfield, by 1960 these figures were down to 84,000 miners producing 19,537,000 tons of coal. Relative wages of the miners were also losing ground, in 1952 the South Wales miner earned £1.92 per shift as compared to £2.08 on average for the U.K., by 1959 the South Wales average had risen to £2.78 but the U.K. average had gone up to £3.02. For the miners of South Wales, the 1960s are remembered as the era of pit closures. Not that pit closures had been accelerated, 76 pits closed between 1960 and 1970 in the Coalfield, exactly the same number that had been closed between 1947 and 1959, but because the number of collieries in operation was less, and that the closure programme was mainly carried out under a Labour Government, and under an NCB chairman, Sir Alf Robens, who at one time had designs on the Labour Party leadership, they appeared to be more severe than in the past.

In 1960, 118 collieries produced 19,537,000 tons of coal with the manpower at 84,000 by 1970 the 52 collieries left in operation produced 11,685,478 tons of coal with a workforce of 38,000. In 1960, in Monmouthshire there were 24 pits in operation employing 16,640 men, by the end of that decade 9 pits were left employing 3,943 men, in 1970 there were only three pits left in the Rhondda Valleys; Fernhill at the top of the Rhondda Fawr, Mardy at the top of the Rhondda Fach and Lewis Merthyr/Ty Mawr at the mouth of the Valley. This mass closure policy had the desired effect of improving the output per manshift at collieries; it went up from 20.6cwts in 1960 to 28 cwts in 1970, but failed in its attempts to stem the huge losses that the Division was running up. From the position of showing a small profit of £1.00 per ton in 1950, by 1960 the Division was showing a loss of £28.00 per ton, and by 1970, despite all the closures, losses were running at £41.00 per ton.

The simple fact was that during the 1960s coal’s main customers were turning to other cheaper sources for their energy, mainly oil as can be illustrated by showing sales comparisons between 1960 and 1970; during that period orders from the power stations fell from 4,380,000 tons to 3,433,000 tons, the gas market disappeared altogether, the coke market dropped from 6,151,000 tons of coal to 5,089,000 tons, the railway market fell from 1,481,000 tons to a paltry 14,000 tons and industrial orders fell from 2,214,000 tons to 759,000 tons. It was only in the house coal market that there was a slight increase in sales from 2,541,000 tons to 2,598,000 tons of coal. in 1964, and the aura of uncertainty caused by the apparently random way that collieries were closed created a despondency amongst the men that caused them to leave the industry in droves, with the resultant closure of potentially profitable pits so that their manpower could be used to fill empty places at neighbouring pits.

Maritime Colliery failed to survive the closure programme and was closed by the National Coal Board on the 23rd of June 1961 to supply Cwm Colliery with manpower. Amongst other seams, this pit extensively worked the Middle and Upper Seven-Feet seam at a section of around 42 inches, and the Upper-Nine-Feet seam, locally known as the Six-Feet, was worked at a thickness of around 54 inches. Generally, this colliery’s coals were classed as type 301A prime coking coal and were used for foundry and blast furnace coke.

Some Statistics:

- 1889: Output: 120,767 tons.

- 1894: Output: 34,066 tons.

- 1896: Manpower: 328.

- 1899: Manpower: 368.

- 1900: Manpower: Pit: 275. Level: 174.

- 1901: Manpower: Pit: 348. Level: 241.

- 1902: Manpower: Pit: 374. Level: 223.

- 1905: Manpower: Pit: 102. Level: 380.

- 1907: Manpower: 235.

- 1908: Manpower: 456.

- 1909:Manpower: Pit: 456. Level: 381.

- 1910: Manpower: Pit: 695. Level: 93.

- 1913: Manpower: 843.

- 1915: Manpower: 830.

- 1916: Manpower: 830.

- 1918: Manpower: 956.

- 1919: Manpower: 950.

- 1920: Manpower: 1,106.

- 1925: Manpower: 1,280.

- 1927: Manpower: 1,275.

- 1928: Manpower: 1,382.

- 1930: Manpower: 1,423.

- 1931: Manpower: 943.

- 1932: Manpower: 733.

- 1933: Manpower: 695.

- 1934: Manpower: 465.

- 1935: Manpower: 720. Output: 200,000 tons.

- 1937: Manpower: 208.

- 1938: Manpower: 297.

- 1940: Manpower: 320.

- 1941: Manpower: 371.

- 1942: Manpower: 376.

- 1944: Manpower: 369.

- 1945: Manpower: 393.

- 1947: Manpower: 414.

- 1948: Manpower: 384. Output: 120,000 tons.

- 1950: Manpower: 365.

- 1953: Manpower: 381. Output: 119,200 tons.

- 1954: Manpower: 404. Output: 96,000 tons.

- 1955: Manpower: 338. Output: 78,167 tons.

- 1956: Manpower: 398. Output: 74,787 tons.

- 1957: Manpower: 413. Output: 85,738 tons.

- 1958: Manpower: 388. Output: 86,570 tons.

- 1959: Manpower: 412.

- 1960: Manpower: 357. Output: 82,842 tons.

For further information, please see the page on Cwm Colliery.

A series of levels worked the Forest Fach and No.2 Rhondda seams as part of Maritime Colliery. They employed 238 men in 1908. Located around national grid reference 068896, they produced steam, house, and coking coals as well as fireclay between 1898 and 1911. In 1905 the miners held a prayer meeting every morning 300 yards in from the mouth of the level.

- 1901: Manpower: 241.

- 1902: Manpower: 223.

- 1903: Manpower: 248.

- 1905: Manpower: 380.

- 1906: Manpower: 392.

- 1907: Manpower: 398.

- 1908: Manpower: 381.

- 1909: Manpower: 94.

- 1910: Manpower: 93.

Information supplied by Ray Lawrence and used here with his permission.