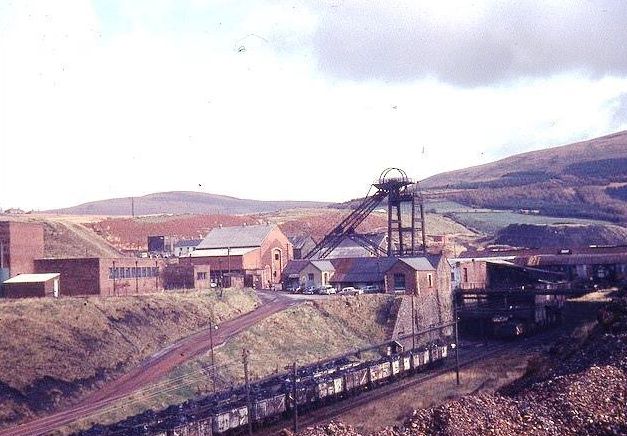

Caerau, Llynfi Valley (SS 8659 9455)

Caerau, Llynfi Valley (SS 8659 9455)

This colliery was bounded by Nantewlaith Colliery to the north, Avon Colliery to the east and Coegnant Colliery to the south. It was sunk by North’s Navigation Collieries (1899) Limited which had been formed from the ashes of the Llynvi, Tondu and Ogmore Coal and Iron Company by Colonel J.T. North and partners in 1899 with a capital of £450,000. Under the guidance of Colonel North and the mining engineer T. Forster Brown, the Company acquired further mineral leases in the Llynfi and Ogmore Valleys and amongst others sunk Caerau Colliery, finally holding mineral leases for 10,000 acres.

Generally, Caerau coals were classed as type 203 Coking Steam Coals, weak to medium caking, low volatile, low ash and sulphur content, and usually used for steam raising, foundry or blast furnace coke.

By 1913 the Company controlled the largest pits in the Maesteg area in Caerau, Coegnant, Maesteg Deep and St.John’s and employed 5,150 men.

In 1916 the Company came under the control of Lord Rhondda, although it retained its name and expanded in 1920 when it bought Celtic Collieries Limited. By 1922 almost £3,000,000 had been paid out in dividends to shareholders.

In 1935 the Company employed 4,104 men producing one million tons of coal in the following pits; Caerau, Coegnant, Maesteg Deep and St. John’s, the Company also owned 50 recovery, and 60 non-recovery coke ovens.

Along with Lord Rhondda’s other holdings, this Company was merged into Welsh Associated Collieries in 1929, which itself was merged into Powell Duffryn Associated Collieries in 1935.

The two steam coal pits of this colliery were sunk between 1889 and 1893. The No.1 or North Pit (downcast ventilation shaft) was sunk to a depth of 1,066 feet 6 inches, the winding engine for this pit was built by Messrs. Thornwell & Warham and had 34-inch diameter cylinders with a stroke of 5 feet 6 inches. The drum was cylindrical in shape and had a diameter of 16 feet. The No.2 or South Pit (upcast) was sunk to a depth of 1,052 feet 7 inches. Both pits were 20 feet in diameter, with the sinking’s costing £180,000.

The No.3 Pit was sunk in 1909 to the Caedavid bottom coal seam which it struck at a depth of 517 feet. It served as the house coal pit for the colliery.

Pre nationalisation the South Pit was capable of winding 1,600 tons of coal per eight-hour shift, the electrical haulages in both pits consisted of two 500 h.p. and three 300 h.p. engines plus compressed air haulages near the coalfaces. There was a “ring main” system of electrical supply with power stations at Caerau, Coegnant and St.John’s collieries linked together.

Early ventilation was by a Walker Indestructible fan which was 24 feet in diameter and 8 feet wide and was installed in 1897.

In March 1894, the director’s report for the company stated that:

The new shafts at Caerauhave been sunk to the Six-Foot seam of steam coal, and a number of drivages through the shaft pillar have been completed. A face of coal has been opened on the eastern side of the pillar which proves of excellent section and quality. The company is now raising about 1,000 tons per week, and anticipate that, with the additional machinery about to be erected, the output will be increased to about 2,000 tons per week within the next twelve months.

On the 20th of June 1894, during a strike and lock-out, blacklegs were brought in to work at this pit. On that day, the strikers and supporters, about a thousand of them, surrounded the houses of the strike-breakers, dragged them out, dressed them in all sorts of clothing, then tied them together and marched them to Maesteg Town Hall where they agreed not to go back to work.

On April 10th 1896, work had just started following the pit being closed for several months “through a misunderstanding” with the men.It was reported that they could produce 400 tons a day at that time, increasing to 1,000 tons by the end of the year. Further capital would then be required to reach the maximum production figure of 2,000 tons a day.

In 1896 there was also a No.2 Level owned by this company which employed 2 men underground and 1 man on the surface, while the South Pit employed 450 men underground and 83 men on the surface.

In 1900 Charles Thomas was only thirteen years of age and W.G. Mitchell was only twelve years of age when run over and killed by trams. Both were employed as door boys and were just two of the many who died at this pit.

The manager in 1893 was James Tamblyn, in 1896 it was J.T. Salathiel, in 1899/12 it was Jenkin Jones and the manager of the No.1 Pit in 1916. In 1915 the manager was David Evans.

In 1910 output of coal was down to 46,801 tons of coal for the year, due to abnormal geological conditions. The selling price of coal was 10s 8d per ton which was a penny less than it took to produce in some districts of the mine.

The No.3 Pit employed 329 men in 1916 when it was managed by J. Martyn and 200 men in 1919 when it was managed by E. James. This pit met with little success and again only produced 40,000 tons of coal in 1920, it was closed in 1925.

During this period, the men working at Caerau were members of the South Wales Miners federation’s, Maesteg District, along with Avon Ocean, Caerau, Coegnant, Maesteg Deep, Maesteg Merthyr, Llangynwyd Garth, Bryn, Cefn-y-Bryn, Cwmdu, Tondu Artisans, Bryn Mercantile, Cwmduffryn, Cwmgwyneu, Glenhafod, Llynfi Sundries.

Caerau Colliery cannot be divorced from the turbulent events of the mining industry in South Wales, so I have set out below the major industrial disputes of the Caerau era.

THE SLIDING SCALE AGREEMENT FOR WAGES

The deep depression in the iron trade throughout the world around 1870 forced the great ironworks of South Wales to either close or drastically reduce output. This in turn made the ironmasters look for new ways to make a profit.

As the majority was already owners of coal mines primarily used to fuel their works they now turned this production of coal into the already highly competitive coal market. The recent boom in iron production had forced the mine owners to pay relatively high wages to attract workers into the pits, their efforts to cut costs to those of the ironmasters so that they could remain competitive, coupled with the new government legislation which permitted the organisation of labour resulted in four years of tussles which in itself led to the Sliding Scale Agreement of 1875.

In February of 1871 the coal owners demanded a 10% reduction in wages, the main representatives of the miners in South Wales at that time, the Amalgamated Association of Miners, countered with a demand for a 10% rise in wages. The result of this difference in opinions was a twelve-week long strike that gave only a slight increase in wages A further effect of this dispute was that it was partly responsible for the formation of the coal owners own ‘trade union’ in the shape of the Monmouthshire and South Wales Coal Owners Association. This Association (or South Wales Coal Trust) banged the negotiating table again in January of 1872 and demanded another 10% reduction in wages for the miners. The Amalgamated Association of Miners again called for a withdrawal of labour but the strike rapidly collapsed and the men returned to work on the owner’s terms.

In 1874 the price of coal fell from 22/- (£1.10) per ton to 12/- (6Op) per ton and the coal owners again asked for a 10% reduction in wages which then would be brought down to 4/4.5d (22p) per day. On the First of January 1875, the miners withdrew their labour and started a five month period of strikes and lock-outs by the owners. In April of that year, the owners increased the demand for a reduction of 15%. On the 31st of May, the miners were forced to return to work having accepted a 12.5% reduction in their wages. It was from this date that it was agreed that wages should be regulated by a sliding scale according to the selling price of coal. With some amendments, this system continued in practice until the Conciliation Board was formed in 1902.

Following the strikes and lock-outs of 1875, the Amalgamated Association of Miners became bankrupt and was dissolved.

The Sliding Scale Association was led on the coal owners side by W.T. Lewis (later Lord Merthyr), and on the workmen’s side by William Abraham (Mabon). The standard wage was to be calculated at 5% above the wages paid in 1869, from then on wages were to be adjusted at six-monthly periods and to be regulated by the net selling price of coal, i.e. a change in the net selling price of coal at the ports of one shilling per ton was to involve a change of 7.5% in the standard wage. Revisions were made in 1880, 1882, 1890 and 1898. During the first four years of working wages reduced firstly by 7.5%, and then by 10%, it wasn’t until 1882 that wages reached the 1869 levels.

The Fourth Sliding Scale Agreement was signed on the 15th of January 1890 and stated that standard wage rates on which future advances or reductions were to be made would be based on wages paid in December 1879, i.e. a reduction in the basis for calculation, they were to be equivalent to a standard net selling price of coal of between 7/lOd a ton and under 8/- a ton. The selling price was to be ascertained by two accountants, one appointed by either side, in a quarterly audit. For each rise or fall of one shilling per ton, wages were to rise or fall by 10%.

Under this agreement wages rose to 57% of standard by mid-1891 prompting the owners to give six months notice to cut the rate from 10% to 8.75% Wages then tumbled to 10% above standard level by July 1893, they rose again to 30% in May 1894, and then fell back down to 10% in July 1893. The Agreement was now despised by the workmen with its heavy bias towards the owners who would demand a reduction in the ratio every time there was a rapid increase in the price of coal and would enjoy a three-month ‘honeymoon’ before wage rises were given. In 1897 the workman demanded a 10% rise on the minimum and were refused, in September 1897 a conference of the colliers that were under the Sliding Scale voted by 41,880 votes to 12,178 votes to give notice to end it. Negotiations with the owners failed, and at the beginning of April the men came out for the 10% rise. The owners’ refused to negotiate and rebuffed the Government by refusing conciliation, so by the beginning of September the men were forced to return to work on the owners’ terms.

On the First of September 1898 a new Sliding Scale Agreement was signed, part of which abolished the long-established holiday called Mabon’s Day, forcing the agreement to last until January 1903, and basing wages on 17.5% above the 1879 standard.

The outbreak of the First Boer War rapidly increased the demand for coal and both coal prices and wages increased, wages rose to 78.75% above standard, but by mid 1902 had dropped back to 48.75%. On the First of July 1902, the workmen gave the requisite six-months notice to end the Sliding Scale Agreement

1893 – The British coal owners call for a 10% reduction in wages. As South Wales was tied to the Sliding Scale Agreement it continued to work throughout the 15-week strike covering August to November. The Miners Federation of Great Britain then tried to close the South Wales Coalfield through a strike of the hauliers. The hauliers marched from pit to pit in an attempt to close them this led to pitched battles between the hauliers and the other miners and resulted in the military being brought in.

- 1898 – The miner’s demand for a 10% increase in wages was defeated after a four-month lock-out. The failure of this strike was the main reason why the local district unions decided to amalgamate and form the South Wales Miners Federation.

- 1899 – The SWMF affiliates to the MFGB.

- 1903 – The Sliding Scale Agreement was replaced by the Conciliation Board Agreement.

- 1911 – In this year the following men were involved in industrial disputes. Ogmore Vale, 719 men involved from January to August. Neath Valley, 833 men were involved from February to October. Rhondda Valley, 5,800 men involved from 14th to 17th October.

- 1912 – Throughout Great Britain, one million men were involved from 26th February to 15th April in a strike for a National Minimum Wage – the strike was successful.

- 1913 – In this year the following were involved in industrial disputes. South Wales 50,000 men involved from 2nd to 8th May.

- 1915 – In July the South Wales Coalfield comes under the Munitions of War Act after an Area Conference called for a new wage agreement. Following a five day strike, the Government concedes the main demands. In November the South Wales Coalfield is brought under State control.

In this year the following were involved in industrial disputes South Wales 60,000 men involved from 1st to 3rd July. South Wales 200,000 men involved from 15th to 21st July.

In South Wales, 10,000 men were involved from 25th August to 1st September and 20,000 men were involved on the 1st of September.

- 1917 – South Wales, 2.600 men involved in a strike from 1st to 3rd November.

- 1919 – The Sankey Commission recommends the Nationalisation of Mines but the Government takes no action. The seven-hour day is introduced. South Wales/Midlands/Yorkshire there were 100,000 men involved in strike action between the 24th to 29th of March

- 1920 – Great Britain, 1,100,000 men were involved in strike action from 16th October to 1st November.

THE 1921 LOCK-OUT

In February of 1921, a worldwide trade depression had hit the mainly exporting South Wales Coalfield particularly bad with 80,000 miners laid off. The mines were still under State control following the war, and as a result, the miners were enjoying their highest wages in history at 21 shillings and 6.75 pence per shift, due to the agreement of 1920 which gave an output bonus of 3/6d per shift.

The Government then surprised and horrified the miners by stating that they were bringing forward the end of state control of the mines to the end of March. The owners then immediately announced that there would be a drastic cut in wages. On the 16th of March, they issued notices to all workmen (including pumpsman) that all contracts of services would end on the 31st of March.

On Friday the First of April 1921 over 1 million miners nationally were locked out of the mines until they worked on the owners’ terms. As the contract notices included the pumps men they also stayed out of work (much to the distress of the owners and government) and the pits were left to flood. The government then proclaimed a State of Emergency and troops were moved into the coalfields. The government refused to allow negotiations to continue unless the pumpmen worked so they were allowed to return on the 9th of April. This changed the whole position of the dispute, from a state of panic the owners and the government now had control of the situation, due to the slump in trade the demand for coal had reduced, and the pits were now safe for re-opening when required. Negotiations broke down on the 12th of April, and on the 14th of April, the Railway and Transport Unions withdrew their threat of support strike action.

Despite all this, the miners refused to accept the owner’s terms and continued to remain out of work, in June a ballot of all miners still rejected the owner’s terms, hi South Wales by 110,616 votes to 40,909 votes, and Nationally by 435,614 votes to 180,724 votes. The National Executive Committee of the Miners Federation of Great Britain literally ignored this result and carried negotiations which resulted in a disastrous settlement for the miners. Following backstage plotting their recommendations were accepted by area conferences, South Wales voted 112 to 109, and the men returned to work defeated. In South Wales, miners’ wages per shift dropped to under half by October 1922 at nine shillings and five and a half pence. The MFGB justified their actions in the following terms in their recommendation leaflet dated 28th June 1921:

Your Executive Committee has today provisionally agreed to terms of a wages settlement with the Government and the owners. These terms are brought to your notice herewith with the object of getting them ratified, so that a general resumption of work may take place on Monday next. The important and responsible step of taking power as a Committee to negotiate a wages settlement, even after the last ballot vote, was the result of our certain knowledge that the National Wages Board, with the National Profits Pool, could not be secured by a continuation of the struggle, we took upon ourselves the freedom to negotiate a wages settlement. This wages settlement which is now before you represents the maximum that can be secured in the present circumstances.

Up to now, the unity of the men has been magnificent, whole districts which had nothing to gain in the form of wages have stood loyally by the other districts whose wage reductions would have been of the most drastic character. This loyalty and unity will have been maintained to the end of the dispute, despite the great odds against us, if a general resumption of work takes place on Monday next. We therefore strongly urge you, with the knowledge of the seriousness of the situation, to accept this agreement, which we have provisionally agreed to today, and authorise your Committee to sign the terms by Friday next.

THE 1926 GENERAL STRIKE AND LOCK-OUT

The reason for this strike can be encapsulated in the slogan ‘not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day.’ Yet again the coal owners demanded concessions from the miners. The miners refused to accept the owner’s terms, and on the 30th of April 1926 the lock-out notices expired and the pits stopped. Amongst much confusion and dithering the General Council of the Trades Union Congress approved of the strike and a General Strike of all the workers of the U.K. was called from the 4th of May. The state of confusion, the lack of compromise from the government who totally supported the owners, coupled with the government propaganda that it was really a ‘red revolution’ caused the General Strike to collapse on the 12th of May 1926.

The British miners, and especially the South Wales Miners Federation, shrugged off this inconvenience and continued to struggle alone. In the valleys of South Wales civil authority virtually ceased to have any effect as the striking miners and their families took control of every aspect of their lives. This was the time of the soup kitchens, the presence of such meaning was far more than just the provision of food, they epitomised the community spirit of the valleys.

Eight weeks on, and the SWMF could proudly inform the Miners Federation of Great Britain that the strike was solid in South Wales with the exception of twenty men developing Taff Merthyr Colliery. Things were really tough by August when most of the Rhondda was reported to be on a diet of bread and bully beef, yet the miners remained defiant, treating the Bishops proposals for a settlement with contempt. It was in the last eight weeks of the strike that the frustrations began to surface, eighteen major clashes with the police occurred, mainly while they were escorting ‘blacklegs’ back to work. A decision in October by the SWMF to withdraw all safety men working in the pits caused further police reinforcements to be brought into the valleys, and therefore to increase the tension.

On November 23/24th, the South Wales Executive Committee met the Owners but failed to agree on terms. On November 29th a ballot of the south Wales miners voted in favour of a settlement, and on the 1st December 1926, the miners returned to work on the Owners terms. Defeated.

At least some returned to work, activists and many lodge officials were refused work, and other strikers at pits such as Meiros, Raglan, Wern Tarw, Lanelay and Bryncae found that their places had been filled by blackleg labour.

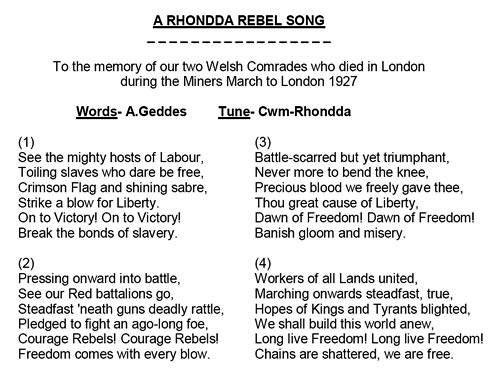

1927 – The first Welsh hunger marches to London. The first hunger march from Wales to London took place in 1927 as a protest against the Ministry of Health who were refusing or limiting relief notes to unemployed miners and their families. It was also a demonstration against the Government’s new Unemployment Bill.

Red Sunday in Rhondda Valley

During a demonstration on 18 September 1927 — ‘Red Sunday in Rhondda Valley’ — A. J. Cook, the miners’ leader at the time, called for a march to London on 8 November (when Parliament re-opened). Every South Wales Miners’ Federation (SWMF) lodge (colliery union branch) chose members to march, and each marcher would carry a miner’s safety lamp.

By November the march had lost the support of the SWMF. However, it was still supported by A. J. Cook, S. O. Davies (later MP for Merthyr), the SWMF Rhondda section and the Communist Party.

On 8 November 1927, 270 men eventually marched in spite of hostility from the trades unions, press and government. They did, however, gain support from Trades Councils in every town and village they passed through (which included Pontypridd, Newport, Bristol, Bath, Chippenham and Swindon).

Soldiers in a Workers Army

The 270 marchers came from the Rhondda Valleys, Caerau, Aberdare, Merthyr, Pontypridd, Tonyrefail, Ogmore Valley, Gilfach Goch, Nantyglo and Blaina. Two miners died on the march – Arthur Howe from Trealaw in a traffic accident and John Supple of Tonyrefail who died after catching pneumonia during the rally in Trafalgar Square.

In his last letter to his wife Mr Supple had written — ‘Don’t worry about me. Think of me as a soldier in the Workers’ Army. Remember that I have marched for you and others in want.’

‘Fascists’ harassment and Armed Escorts

From the beginning, the march was frequently referred to as a ‘workers’ army’. The marchers had been organized on military lines, divided into detachments and companies. During the march there was alleged harassment by ‘Fascists’, causing the organizers to be met by an armed escort of 100 members of the Labour League of Ex-Servicemen at Chiswick.

From the beginning, the march was frequently referred to as a ‘workers’ army’. The marchers had been organized on military lines, divided into detachments and companies. During the march there was alleged harassment by ‘Fascists’, causing the organizers to be met by an armed escort of 100 members of the Labour League of Ex-Servicemen at Chiswick.

The ‘Workers’ Army’ senior ‘officer’, Wal Hannington, later wrote in a pamphlet entitled ‘The March of the Miners: How we Smashed the Opposition’: ‘… these men are lighting a lamp stronger and more powerful than that which they are carrying. They are lighting a lamp that reveals the tortuous path the toilers have had to follow, and which lights up the road of struggle for the battle with the forces of reaction and the conquest of power by the workers’.

The pamphlet includes ‘A Rhondda Rebel Song’ echoing James Connolly’s ‘A Rebel Song’ which, along with ‘March Song of the Red Army’ and ‘The Red Army March’, was sung by the marchers.

- 1930 – The second hunger march to London. SWMF falls to its lowest membership in the inter wars period at 62,089 members.

- 1931 – A strike against the Schillar Award involved 14,000 miners from the 1st to the 17th of January.

- 1932 – The third Welsh hunger march to London.

- 1933 – A strike in the anthracite section of the Coalfield involves 15,000 men from the 14th to the 19th of August. 1935 – Strikes against the new unemployed regulations and non-unionism. 14,500 men on strike between the 30th of September and the 9th of October and 55,000 on strike between the 14th and the 25th of October.

- 1936 – More non-unionism disturbances at Taff Merthyr Colliery. The fourth and largest Welsh Hunger March to London.

- 1938 – 9,700 men on strike on the 11th of July

- 1939 – 5,880 men involved in strike action between the 23rd and 25th of January.

- 1942 – 8,500 miners on strike between the 27th of May and the 6th of June. During February and March a spate of unofficial strikes broke out in the Coalfield against the advice of the Executive Council of the Federation. The strikes were partly due to discontent over the Porter Award on house coal and the minimum wage, and partly due to other factors including perhaps war-weariness. On the 6th of March 10,000 men were on strike in the Monmouthshire District, with the strike rapidly moving westwards so that by the 8th of March, 150 pits were idle and 85,000 men on strike. 500,000 tons of coal was lost in a week of anarchy. The result of this action was that in future all agreements were to last for four years. The National Union of Mineworkers is formed.

- 1946 – Arthur Horner elected as General Secretary of the NUM.

- 1947 – Nationalisation of the Coal Industry.

- 1951 – 12,000 miners out on strike between the 7th and 29th of June.

- 1952 – 6,000 miners strike between the 30th of April and the 9th of May and 22,000 strike between the 18th and 22nd of August.

- 1953 – The first South Wales Miners Gala.

- 1959 – The beginning of the massive closure programme. Will Paynter elected General Secretary of the NUM.

- 1969 – A growing resurgence of militarism following the mass closures of the late 1950s and 1960s led to unofficial disputes over surface-men wages and pit closures.

- 1972 – The 1972 strike was the first total strike of all miners since 1926. Miners’ wages had slipped from nearly the top of the industrial wages league to fourteenth place. To redress this slide a resolution was passed in the NUM Conference of July 1971 demanding a wage of £26 for surface workers, £28 for underground workers and£35 for coalface workers. An overtime ban commenced on the 31st of October within December a ballot voting 145,482 to l0l,9l0 for a strike. 65.5% of the south Wales miners who voted supported the strike call. During the 1972 miner’s strike for increased wages, the Caerau NUM Lodge gained the disapproval of the NUM by withdrawing the safety men from the pit. On the first of January the strike commenced and by February industry had been placed on a three day week. On the 28th of February, the miners returned to work victorious.

- 1974 – Again the miners found themselves sliding down the wages league. 93.5% of the South Wales miners who w supported strike action over the claim for a wage of £35 for surface workers, £40 for underground workers and £45 for coalface workers. The trusted procedure of an overtime ban front the 1st of November led to an all-out strike from the 9th of February which lasted for four weeks. Again a state of emergency was called, a three day week implemented, and finally, a General Election was called for the 28th of February.

Bad times had certainly hit the Coalfield, in 1921, 271,161 miners had produced 46,249,000 tons of coal, 20.1% of the U.K.’s total, by 1939 there were only 128,774 men at work producing 35,269,000 tons of coal, 15.2% of the U.K.’s. total. In 1931 unemployed within the Coalfield stood at 36% rising to an incredible 47% in 1932, in the period 1933, 1934, 1935 the figures remained devastatingly high at 42%, 44% and 34% respectively, indeed they could have been much higher except for the relative prosperity of the anthracite section of the Coalfield, and for workmen leaving the area to seek work elsewhere – almost 22,000 men in the period 1931 to 1935.

The Rhondda/Port Talbot registration area was particularly badly hit during this period with unemployment peaking at 60% in 1932. It was only re-armament and the threat of another war with Germany that brought about a huge demand for coal again. On the 15th of January 1934 this pit re opened after two years of inactivity. At that time it employed 219 men on the surface and 1,326 men underground. The manager at that time was David Evans while D.M. Rees was the manager in 1937. The manager in 1943/5 was A.P. Pomeroy and the colliery employed 485 men working in the Red, Six Feet and Lower New seams and 101 men working on the surface of the mine.

Along with the rest of the Nation’s major coal mines, Caerau was Nationalised in 1947. The National Coal Board placed the pit in the South Western Divisions No.2 (Tondu) Area, Maesteg Group, at that time it employed 505 men underground and 133 men on the surface working the Red, Lower New, Upper New and Harvey seams. The manager was E.M. Thomas who was still there in 1950.

In May 1952, the technical staff at Caerau Colliery broke the National record for changing the drum shaft on the winding engine drum. This job normally takes between seven and ten days, but at Caerau it was completed in 53 hours!

In April 1953, six miners were engaged in clearing a roof fall for six hours unaware that another fall, half a mile from them, and on the way to pit-bottom had blocked their only way out. For five hours, twenty-three rescuers toiled at the second fall before they were able to notify the trapped men about their situation. It took another seventeen hours before they could be brought to the surface. Food and drink was supplied to them by being pushed through a compressed air pipe that travelled into the district. The trapped men were; R. Evans, cutterman, R. Hicks & R. Williams, repairers, D. Gunn, assistant repairer and G. Emmitt and J. O. Howell, both colliers.

When opening a new pit-head baths and medical centre, which cost £75,000, on Saturday, 6thof March 1954, the chairman of the South Western Division of the NCB, D. M. Rees, warned; “If these welfare amenities are necessary I am not concerned with what they cost to provide, but the men in Caerau must sit down and take stock of the position and show that they are genuinely appreciative of what is being done for them, both by aiming at greater harmony and increased production.” Both he and the NUM were unhappy over the number of wildcat strikes and petty disputes in the district with Mr. Rees adding; “If this continues the board will be forced to take steps which will hurt only the people engaged in the industry in the long run.”

In 1954 the manager was B.O. Williams, and in 1955 out of the 825 men employed at this colliery, 419 of them worked at the coalfaces. The coalface figure dropped dramatically to 364 men in 1956, and further down to 353 men in 1958.

In September 1960, Caerau was working the Lower Five Feet seam with a section of coal of 54 inches. The coalface was undercut with a machine, but the NCB and the Union couldn’t agree to a payment for the colliers. The matter eventually landed up with the Umpires who were hand-picked to resolve issues such as this. The price list paid to the colliers was given as 2s.11d (15p) per square yard of coal filled onto the conveyor.

In 1969/72 the manager was L.S. Rees and in 1975/78 it was W.C. Nicholas. In 1969 it was working the Lower and Upper Nine-Feet seam. In February 1972 Caerau Colliery became the first colliery in the West Wales Area to come off the NCB’s Jeopardy (closure) list with its reward being the mechanisation of the coalfaces. The Lower Nine Feet seam was developed and the coalface was equipped with Anderton disc cutters and hydraulic roof supports.

Caerau Colliery was closed by the National Coal Board on the 26th of August 1977, due to exhaustion of the coal seams.

Some of the early fatalities at this colliery:

- 7/3/1890, Thomas Jones, aged 47, sinker, trolley fell down the shaft.

- 11/11/1893, William Davies, aged 15, collier boy, fall of roof.

- 11/12/1897, Robert James, aged 48, cogman, asphyxia.

- 12/1/1898, Evan Jenkins, aged 54, labourer, rupture.

- 12/9/1898, Henry Thomas, aged 48, assistant repairer, fall of roof.

- 6/10/1898, Isaac Evans, aged 28, collier, fall of roof.

- 27/7/1899, John Phillips, aged 22, hitcher, coal fell down shaft.

- 25/11/1910, D. J. Jones, aged 16, assistant collier, fall of roof.

- 8/2/1911, Lewis Williams, aged 24, repairer, fall of roof.

- 10/4/1911, Llewellyn Lewis, aged 29, collier, fall of roof.

- 5/9/1911, David Jones, aged 36, repairer, fall of roof.

- 10/6/1912, Stephen Furlong, aged 62, surface labourer, crushed by trams.

- 10/12/1912, Robert J. Roberts, aged 20, all of roof.

- 3/6/1913, Ernest Burgess, aged 46, haulier, fall of roof.

- 1/7/1913, James Lawler, aged 15, assistant collier, fall of roof.

- 27/7/1913, Owen Williams, aged 36, repairer, fall of roof.

- 31/1/1914, Gwilym Duncan, aged 39, haulier, fall of roof.

- 20/3/1914, Edward Arthur Webb, aged 16, assistant collier, fall of roof.

- 21/10/1914, George Williams, aged 34, collier, fall of roof.

- 2/7/1925, W. Bowen, aged 70, fireman, run over by trams.

- 5/10/1925, Stephen Davies, aged 58, repairer, David Thomas, aged 46, overman, fall of roof.

- 15/7/1926, Samuel Rees, aged 39, master haulier, run over by trams.

- 22/4/1927, Samuel Lewis, aged 48, repairer, fall of roof.

- 2/3/1929, Edwin Thomas, aged 34, haulier, roof fall.

- 8/4/1929, Ivor Thomas, aged 19, assistant collier, fall of roof.

- 30/10/1929, George Tompkins, aged 31, master haulier, run over by trams.

Some Statistics:

- 1894: Output: 58,714 tons.

- 1899: Manpower: 862.

- 1900: Manpower: 1,095.

- 1901: Manpower: 1,182 Output; 333,907 tons.

- 1902: Manpower: 1,236.

- 1903: Manpower: 1,397.

- 1905: Manpower: 1,496.

- 1907: Manpower: 1,652.

- 1908: Manpower: 1,770.

- 1909: Manpower: 1,770.

- 1910: Manpower: 1,873.

- 1911: Manpower: 1,920.

- 1912: Manpower: 1,903.

- 1913: Manpower 1,988.

- 1915/6: Manpower: 1,988. No.3: 329.

- 1918: Manpower No.1: 1,839. No.3: 179.

- 1919: Manpower: No.1: 1,600. No.3: 200.

- 1920: Manpower: 1,600. No.3 Pit: 200. Output 299,473 tons. No.3: 40,004 tons.

- 1922: Manpower 1,850. No.3 Pit: 320.

- 1923: Manpower: 2,040. No.3: 342.

- 1924: Manpower: 2,026. No.3: 362 1927: Manpower: 1,875.

- 1928: Manpower: 1,266.

- 1929: Manpower: 1,600.

- 1930: Manpower: 1,545.

- 1932: Manpower: 1,600.

- 1934: Manpower 1,545.

- 1937: Manpower: 517.

- 1938: Manpower: 1,022.

- 1940: Manpower 560. Output: 141,773 tons.

- 1943: Manpower: 586.

- 1945: Manpower: 585.

- 1947: Manpower 638.

- 1948: Manpower: 652. Output: 110,000 tons.

- 1949: Manpower: 810. Output: 170,087 tons.

- 1950: Manpower: 816.

- 1953: Manpower: 869. Output: 175,000 tons.

- 1954: Manpower: 806. Output: 167,290 tons.

- 1955: Manpower: 827. Output: 159,688 tons.

- 1956: Manpower: 769. Output: 150,182 tons.

- 1957: Manpower: 765. Output: 140,499 tons.

- 1958: Manpower: 732. Output: 173,166 tons.

- 1960: Manpower: 684. Output: 160,201 tons.

- 1961: Manpower: 641. Output; 122,244 tons

- 1964: Manpower: 595.

- 1969: Manpower: 487.

- 1970: Manpower: 511.

- 1971: Manpower: 528.

- 1972: Manpower: 533.

- 1976: Manpower: 529.

This information has been provided by Ray Lawrence, from books he has written, which contain much more information, including many photographs, maps and plans. Please contact him at welshminingbooks@gmail.com for availability.

Return to previous page