Treharris (Grid Reference 10089738)

Treharris is a small but fast-increasing district, about ten minutes’ walk from Quaker’s Yard Station, and just above the busy hive of industry known as Quaker’s Yard village. The principal industrial authority in the immediate district is Harris’s Navigation Colliery; hundreds of hands are now employed sinking the shafts for coal and a depth of 410 yards has already been achieved but it is reported that the steam coal known to be embedded beneath them will be arrived at – an estimated depth of 750 yards. To meet present and prospective requirements – for there is no commercial hotel properly situated within a radius of many miles of the vicinity, Mr. D. E, Jones, contractor, Treharris, recently decided upon building a hotel at an estimated cost of £4,100. Land for that purpose was leased from Harris’s Navigation Company, who contemplate building within the next two years from 250 to 500 houses in the locality-and on Friday, amid Clapping and round of cheers from a numerous assembly of workmen, the first sod was cut by Miss Martha Jane Jones (Mr. Jones’s daughter). and the architect, Mr. William Davis, of Merthyr. The work of building the hotel will rapidly proceed with and will be finished by next August at furthest.

The sinking of this colliery commenced in February 1873 and was completed to the Nine-Feet seam in May 1878. Two shafts were sunk, 60 yards apart, and with a diameter of 18 feet, the downcast ventilation shaft to a depth of 760 yards, which was 200 yards deeper than any other pit in the South Wales Coalfield to that date, and the third deepest pit in Great Britain. The upcast ventilation shaft was 695 yards deep. The No.1 (South Pit) was the downcast ventilation shaft, and the No.2 (North Pit) was the upcast ventilation shaft. To try and compensate for the depth of the shafts double decked carriages were installed in the No.1 Pit. Each deck carried two trams. The winding engine for the No.1 Pit had a 54-inch-wide cylinder with a seven-foot stroke and a spiral drum that ranged from 18 feet to 32 feet in fourteen coils. The cages were 12 feet long and 4 feet 2 inches wide and carried four trams on two decks. Both decks were loaded/unloaded simultaneously. It could complete a wind in less than a minute. The winding engine for the No.2 Pit had two horizontal cylinders each 3 feet 6 inches in diameter and with a six feet stroke. The winding drum was cylindrical and 18 feet in diameter. The headgear was 81 feet 6 inches high with the winding wheels being 20 feet in diameter.

The sinking of this colliery commenced in February 1873 and was completed to the Nine-Feet seam in May 1878. Two shafts were sunk, 60 yards apart, and with a diameter of 18 feet, the downcast ventilation shaft to a depth of 760 yards, which was 200 yards deeper than any other pit in the South Wales Coalfield to that date, and the third deepest pit in Great Britain. The upcast ventilation shaft was 695 yards deep. The No.1 (South Pit) was the downcast ventilation shaft, and the No.2 (North Pit) was the upcast ventilation shaft. To try and compensate for the depth of the shafts double decked carriages were installed in the No.1 Pit. Each deck carried two trams. The winding engine for the No.1 Pit had a 54-inch-wide cylinder with a seven-foot stroke and a spiral drum that ranged from 18 feet to 32 feet in fourteen coils. The cages were 12 feet long and 4 feet 2 inches wide and carried four trams on two decks. Both decks were loaded/unloaded simultaneously. It could complete a wind in less than a minute. The winding engine for the No.2 Pit had two horizontal cylinders each 3 feet 6 inches in diameter and with a six feet stroke. The winding drum was cylindrical and 18 feet in diameter. The headgear was 81 feet 6 inches high with the winding wheels being 20 feet in diameter.

The surface ventilation fan was 14 feet 3 inches in diameter and produced 230,000 cubic feet of air per minute. Sinking costs came to £300,000 with 168 men employed during the sinking, with seven of these being killed during these operations. It is claimed that the company ran out of money towards the end of the sinking and that the men worked at first reduced, and then no pay for a time.

On the 15th of July 1878 Henry Woodyatt, a 29-year-old sinker was killed by falling off a water barrel whilst descending the shaft.

The pumping engine for the South Pit had a 100-inch diameter cylinder with an eleven-foot stroke. It took eight stages to pump to the surface and delivered 435 gallons of water a minute. At the south pit bottom, the empty trams were forced out of the cage by the full ones. A creeper chain would then take the empty trams to where a journey (train) was made up, the journey was then taken away by haulage engine either to the west level (which was 1,452 yards away) or the upper district. Each journey going to the pit bottom consisted of 34 trams with each tram holding one ton of lump coal. In the north pit single-deck cages held two trams, they were also forced out by the full ones and taken by haulage engine to the north-heading district. The journeys averaged 18 trams and travelled for 1,870 yards. There were also 143 horses working at the colliery.

This pit was originally called Harris’ Navigation Colliery after the principal shareholder, F.W. Harris, who also gave his name to the village of Treharris. The other shareholders were Messrs, Webster, Hill, Hackett, and Judkins, the mineral lease was for a period of 99 years and for an area of 3,500 acres. In 1878 there were two managers listed for the colliery, Messrs, Brown and Adams. In 1884 the manager was John Price and in 1893 it was J.P. Gibbon.

1st July 1879:

COAL WINNING AT THE HARRIS NAVIGATION COLLIERY.

Yesterday one of the most important mining operations which have ever been undertaken in South Wales was brought to a successful issue, by the coal being won at the Harris Navigation Colliery, near Quaker’s Yard. The great depth at which it was believed the coal existed the length of time which the sinking operations have occupied – and the difficulties which have had to be overcome – all contributed to invest this colliery with a special interest and curiosity amongst those concerned in mining matters. The announcement of the coal having at length been won will be a matter of satisfaction to many besides those more immediately concerned. The celebrated Four-feet Seam of coal has been struck at the enormous depth of 698 yards – or more than double the average depth of local collieries. The vein proves to be 5 feet 10 inches thick, and it is found to possess all those fine qualities which have rendered the four-feet vein worked in the adjoining properties of Messrs Nixon, Taylor, and Cory, so exceptionally prized for steam navigation purposes.

The geological conditions are also of the most satisfactory character, and the other conditions are such as to in every respect fulfil the highest anticipations of the promoters of the company. The sinking operations have been proceeding vigorously for nearly seven years. Two pits are being sunk, each of unusual size – being 17 feet in diameter. The coal has been struck in the south pit, which is about 70 yards distant from the north pit and is somewhat more advanced than the latter pit. Some little time will necessarily elapse before the workings will permit of any considerable output of coal, but it is anticipated that a large daily output will be secured within four or five months. and that before long the colliery will be capable of an output of about 2,000 tons per day. The colliery has an area of no less than 3,000 acres. The area is almost square in form, and about two miles from east to west by two and a half miles from north to south.

Three railways run over the property, viz., the Taff Vale, Great Western, and Taff Bargoed lines. The colliery is not only advantageously placed as regards nearness to the port of Cardiff, but it is also in an excellent position for railway communication with Liverpool. Amongst other features of the sinking, we may state that upwards of 200 yards of Pennant rock had to be pierced, and another matter of interest has been the working of a very large Cornish pumping engine, with a cylinder ??? inches, it being the largest pumping engine in South Wales. The management of the company has been in the hands of Messrs Dixon and Harris, of 81 Gracechurch Street, London, the latter-named gentleman (Mr F. W. Harris) being chairman of the company. The local management has been in the hands of Mr Jones, who is personally largely interested in the undertaking. The sinking and engineering arrangements, which have been so successfully carried out, have been in the entire charge of Messrs Brown and Adams, Cardiff – the resident mechanical engineer being Mr W. Beith.

In January 1891 the Deep Navigation Collieries Company took the Rhymney Railway Company to court claiming that they had been overcharged by £13,000 in respect of taking their coals to Cardiff and Penarth docks, while the company was still called Harris’ Navigation Coal Company Limited. That was only part of the problem for the company and soon financial problems crippled Harris’ Navigation Company and Deep Navigation Colliery was purchased by the Ocean Coal Company in 1893 and renamed Deep Navigation.

The following article appeared in the Western Mail on Friday, June, 2nd, 1893:

IMPORTANT COLLIERY AMALGAMATION IN SOUTH WALES. ACQUIREMENT OF THE DEEP NAVIGATION PITS BY THE OCEAN COMPANY.

The directors of the Ocean Coal Company (Limited) and of the Deep Navigation Collieries (Limited) have concluded an arrangement, subject to the adjustment of various incidental matters, under which the active management of the latter company’s undertaking will shortly be assumed by the Ocean Company upon terms which are regarded as mutually advantageous… The Deep Navigation Colliery is situated in the vicinity of Treharris, and is the deepest in the South Wales Coalfield, having been sunk to a depth of 760 yards. This colliery also enjoys the distinction of being worked by the largest pair of winding engines in the district. The coal raised at the Deep Navigation Pits for the year ending 1891, was 446,310 tons.

Little do we realise now that the dangers of coal mining linger on far after the coal has been brought up the pit. The following is an example of what can, and did, happen much later on. On the 12th of October 1894, the steamer Explorer took on 600 tons of Deep Navigation coal while berthed at Liverpool docks. The hatches were then closed. The following morning the stevedores boarded the ship with naked lights and exploded the gas being given off from the coal. Five men were killed and two others were seriously injured.

The colliery employed 1,513 men underground and 333 men on the surface in 1896 with the manager being J.P. Gibbon. The rateable value for the colliery at that time was quoted to be £17,667.

In 1890 two deaths at this colliery stand out, those of Edwards Williams a colliers boy who was trapped under a fall and died on the 17th of March, and that of John Evans a door boy who was killed on the 26th of June. Edward was 14 years of age and John was 12 years of age when he died. Not all fatalities were confined to underground, or to employees. The Western Mail newspaper on the 12thof September 1889 reported:

On Tuesday evening, at a quarter past ten o’clock, William Smith, aged nine years, the son of a collier, was found drowned in a pond which supplies the Deep Navigation Colliery with water. Deceased had gone with another boy to gather blackberries by the side of the pond, and was last seen alive at two o’clock in the afternoon.

In October 1889, when the Welsh Sunday Closing Act, (this Act eventually came into force and closed all pubs to the west of Offa’s Dyke) was being debated, John Price, who was the manager of DN claimed that; “…out of about 1,300 men employed there 200 would be absent on Monday mornings. Some of the men would not come to work until Wednesday or Thursday – until they had finished every farthing that they had.”

The year 1900 was a particularly bad one for the young at this colliery:

- 28th April, W.J. Huggett aged 15 years fell out of the shaft carriage and was killed.

- 12th June, T. Herbert aged 14 years and a door boy was run over by trams and killed.

- 21st July, John Saunders also a door boy was also run over and killed.

- 13th August, Joseph Jones aged 17 years and a collier died under a fall of roof.

- 8th February, George Hartaged 40 years and a haulier was run over by trams and killed.

- 11th November 1902, five men were killed and two injured when a pipe fell onto the shaft carriage that they were travelling in.

- 25th June 1914, both John Jones aged 37 years and John Thomas aged 55 years died under the same fall of roof.

In 1905 there were 150 horses employed underground to haul the trams of coal to the main roadways where the journeys of coal were brought to the pit bottom by compressed air haulages. Each journey consisted of 34 loaded trams. There were 1,800 men at the pit in 1913 the manager at that time was William Jenkins. An advert for the company at that time stated:

Ocean (Merthyr) Steam Coal Proprietors: The Ocean Coal Co. Ltd., 11 Bute Crescent, Cardiff. Output: 9,500 tons per Day. This coal is unrivalled for Steam Navigation and Railway purposes. It is well known in all the Markets of the world for Economy in Consumption, Purity & Durability. It is largely and in many cases exclusively used by the Principal Steam Navigation Companies at Home and Abroad. Ocean (Merthyr) Steam Coal solely, was used by the Cunard Company Steamers Mauretania and Lusitania in creating a Record for the most Rapid Atlantic Passages. The Ocean Company supply the requirements of the English Admiralty for trial trips, for the use of the Royal yachts and other special purposes. The Ocean Coal Company Limited, have the largest unworked area of the celebrated Four Feet Seam of Coal in South Wales.

In 1915 the Business Statistics Company, in its book called ‘South Wales Coal and Iron Companies’ reported that the Company was called the Ocean Coal and Wilsons Limited and this company…

was registered in March 1908, to acquire and hold all or any of the shares of the Ocean Coal Company Ltd, and Wilson, Sons & Co, Ltd, and any Company in which either of such Companies has or have any interest. The Ocean Coal Co, work 9 collieries…the normal annual output of the Collieries is about 2,500,000 tons of coal. Wilson, Sons & Co, has Coal Depots…In addition to their regular business of Coal Merchants and Steamship Agent, the Company owns engineering shops and foundries at Pernambuco, Dakar, Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and has executed many important engineering contracts.

The book continued to state that the assets of the combined company were £4,886,982 with profits of £301,266 available for distribution. The board of directors was; David Davies, Chairman, A.E. Bowen, William Jenkins, Edward Jones, Thomas Evans, Henry Webb, Alfred Harley, E.E.M. Hett and F.J. Yarrow. The manager in 1908/16 was W. Phillips and in 1918/27 it was L. Lewis. The first pit-head baths in the South Wales Coalfield were constructed at Deep Navigation in 1916 (they were replaced by new baths in 1933), and in 1921 a power station was opened to feed both this colliery and Lady Windsor Colliery. The power station was closed in 1960.

In July 1915, the South Wales Coalfield came under the Munitions of War Act after an Area Conference called for a new wage agreement. Following a five-day strike the Government concedes the main demands. In November the South Wales Coalfield is brought under State control. Following the end of World War One, The Sankey Commission of 1919 recommended the nationalisation of the mines on a permanent basis, but the Government decided to take no action.

In December 1919 the 2,000 South Wales Miners Federation members at this pit passed a resolution protesting against the anti-nationalisation resolution that had recently been passed in the local Conservative clubs and declared themselves in favour of nationalisation.

In 1925 the colliery encountered a geological fault in the Six-Feet seam workings which dropped the seam by 43 feet. While driving down to find the seam they found a fossilized tree trunk that was still vertical and measured fifteen feet long by 33 inches in diameter at the bottom tapering to 10 inches at the top. It was donated to the National Museum of Wales. In 1930 the manager was D.G. Richards.

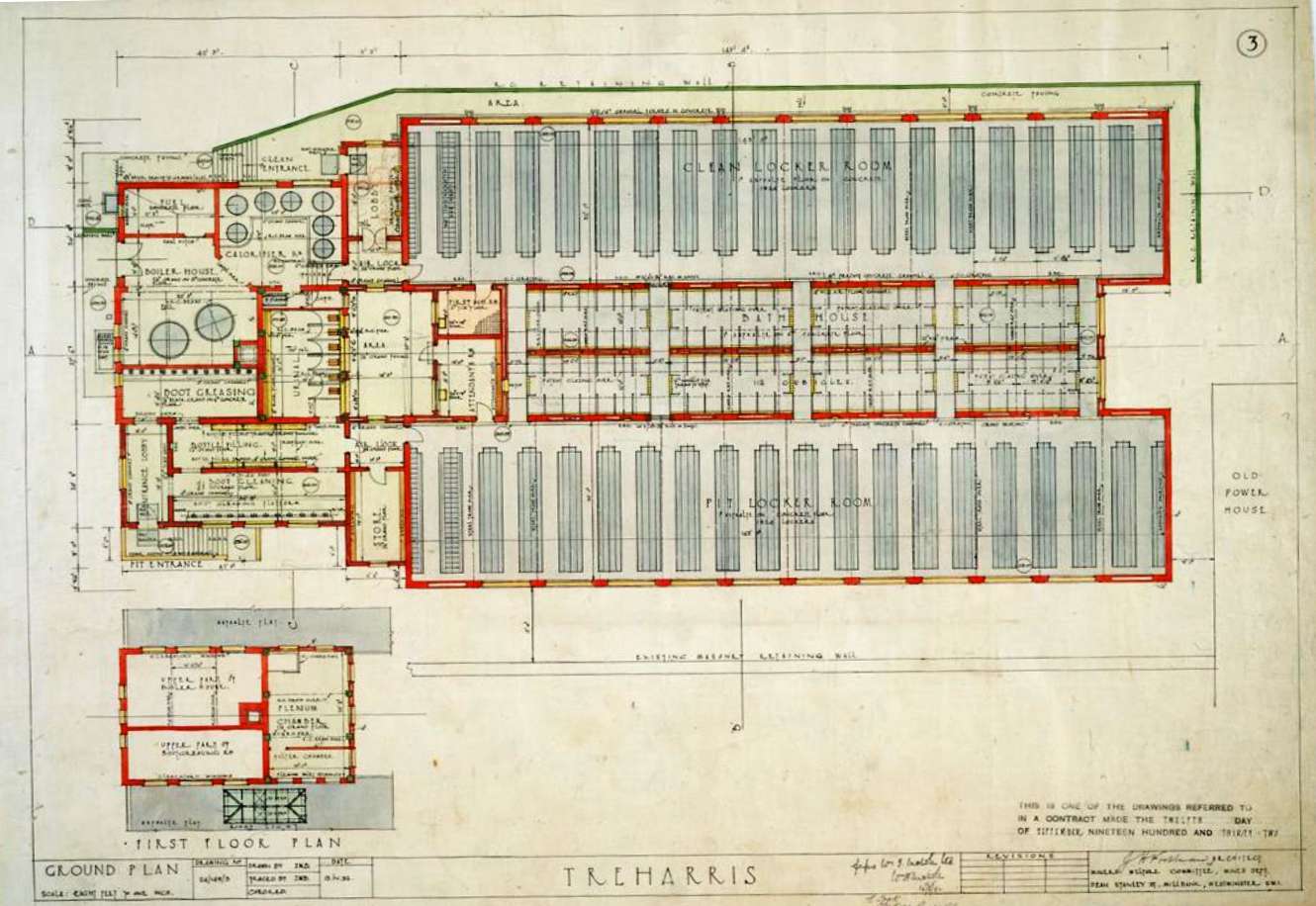

New baths, constructed by Messrs Nicholls & Nicholls of Gloucester, were officially opened on 1st November 1933 by Mr Thomas Evans OBE of Pentyrch, a director of Ocean Coal. The new baths provided accommodation at that time for 1,824 men, who were provided each with two lockers, one for clean and the other for dirty clothes. A report at the time said, “This is a great improvement on the old baths, where clean and dirty clothes hung together on chains in the main hall.” It continued “The whole building is electrically lit, there is also an up-to-date lavatory accommodation and a marvellous machine which cleans the men’s boots by electricity.” The reconstructed baths in 1933 were the 18th in Wales and the 21st in the whole country. Ocean Coal had at that time provided baths at Risca, Wattstown, Lady Windsor, Garw, Nantymeol and Nine Mile Point collieries. Councillor Enoch Morrell. At the same opening ceremony said, “he was pleased to see so many ladies present.” The baths meant a lot to them. They stood for cleaner homes and a higher standard of life.

New baths, constructed by Messrs Nicholls & Nicholls of Gloucester, were officially opened on 1st November 1933 by Mr Thomas Evans OBE of Pentyrch, a director of Ocean Coal. The new baths provided accommodation at that time for 1,824 men, who were provided each with two lockers, one for clean and the other for dirty clothes. A report at the time said, “This is a great improvement on the old baths, where clean and dirty clothes hung together on chains in the main hall.” It continued “The whole building is electrically lit, there is also an up-to-date lavatory accommodation and a marvellous machine which cleans the men’s boots by electricity.” The reconstructed baths in 1933 were the 18th in Wales and the 21st in the whole country. Ocean Coal had at that time provided baths at Risca, Wattstown, Lady Windsor, Garw, Nantymeol and Nine Mile Point collieries. Councillor Enoch Morrell. At the same opening ceremony said, “he was pleased to see so many ladies present.” The baths meant a lot to them. They stood for cleaner homes and a higher standard of life.

In 1934 the Ocean Coal Company Limited was based at 11 Bute Crescent, Cardiff with the directors being Lord Davies, Sir H. Webb, W.P, Thomas, E. Emrys Jones, A.E. Yarrow, A.J. Cruikshank and T. Evans. The company secretary was M.A. Anderson. At that time this company operated nine collieries that employed 7,921 miners who produced 2,750,000 tons of coal.

In 1935 the pit employed 363 men on the surface and 1,875 men underground working the Four-Feet and Nine-Feet steam coal seams. The manager was still D.G. Richards while C.A. Harlow was manager in 1938 and 1943/5 when this pit employed 1,473 men working underground in the Four-Feet, Six-Feet, Nine-Feet and No.4 seams. In January 1942 Comrade Savkov the chairman of the German invaded Don Basin Coalfield of the USSR made a two-hour underground visit along with the mayor of Merthyr, the MP S.O. Davies and trades union officials. By that time the Ocean Company had merged with United National to form the Ocean and United National Collieries Limited.

Doug Evans told Glo Magazine about his experiences:

“I started work in June 1933 at the age of fourteen. The pit was working three days a week at this time and my wages were 2s 5d a day. My brother Eric had got work for me with the fella working in the next stall to him – a man called Hopkin Farr.

The week before I started I had to go over to the pit to meet Hopkin and the overman of the district. Basically as long as you were fit they were willing to take you on. I had to go to the timekeepers and sign on, giving details of my parents, where I lived, my doctor, and the hospital that I came under. Then I had to go down to the lamp room and they gave me a lamp check. If you lost your lamp check it’d cost you, they’d charge half a crown – a day’s wages! The lamp room then noted down the district that I was working in, and Hopkin had to sign that he would be responsible for me.

We were usually over the pit by 6 am. On the day shift, the first bond, or cage, was at 6 am. The colliery hooter used to blow at 6am, at 6.15 am and again at 6.25 am. If you hadn’t got your lamp by 6.25 you would have to go home, and you wouldn’t get paid. The pit hooter was called the ‘old cow’ because it sounded just like one. When we got into the cage us boys were put into the centre with the men standing on either side of us. When you went down in the cage it would take your breath away. When you reached pit bottom most of the night shift were waiting to come up. They never wasted any time winding as they only had half an hour to get all the men down.

The man that you were working with had an electric lamp, but all the boys had oil lamps. So there was a flame lamp in every stall. All the men were capable of telling how much gas there was by using the oil lamp. You had to take care of your lamp as that was your lifeline.

You weren’t allowed to walk the main roadway where the haulage ropes were working and where the coal was taken out, if you got caught on the mains you got the sack. So you had to go down through the air doors and into the return. You were walking then with the warm air that had ventilated all the districts coming towards you before it went up No.2 Pit. So you’d walk along the return airway until you come to your district. Horses used to fetch the trams of coal out of the district to double partings where there were empty trams on one side and full trams on the other. That’s where the haulage started. From there the rope haulage took them back to pit bottom. The individual stalls were each about six feet wide and were driven off tunnels that were called headings. The seam of coal itself was made up of what we called bottom coal, which was the bigger coal, and a top coal which was the smaller coal. Hopkin had a big mandrel for the bottom coal. It gave him more leverage, there were slips in the bottom coal. He knew where these slips were and he could get his mandrel in them to ease them out. Sometimes you had to break this bottom coal to lift it into the tram, it was so big. And then for the top coal, he had a small pick.

Then you had to shovel it all into the dram, but only when there was nobody about as you weren’t supposed to use a shovel! The Powell Duffryn Company insisted that you filled the dram with a curling box to ensure that there was no stone in it – stone that had come off the rippings ‘the rock above the coal seam’. When the overman and the fireman were about the word would pass up the face so you had to use the curling box (a large metal scoop with handles). You had to scrape it in with your hands, lift the curling box and put it in the dram. When they were gone we would use the shovel again. But Hopkin was a clean collier. He would always clear the rippings away to the gob before he started pulling down the coal so that there was no stone about.

The trams had to be bedded and then raced up to about two feet over the rim. You put the small coal inside, you had to keep the big lumps for the top. Powell Duffryn only paid for the colliers for lump coal. The rest would go to the washery and be sold after all. I didn’t know these things at the time. As you got older the colliers would tell you these things, we’d foil five or six drams of coal a shift each holding a little more than a ton.

Sometimes they’d fetch you a load of stone to put into the gob. The man you were working for would get paid sixpence for unloading one of those. Sometimes it was the only way that you would get an empty dram to fill. Sometimes you had to unload three or four of these drams a day. The stone came from the headings on the main level, where they had to take so much of the roof away over the seam of coal to get enough height for the horses. We used to have to bore the shotfiring holes with a ‘butterfly’ hand boring drill. Hopkin would be doing that in his spare time when he was waiting for drams. Then the fireman would ask if the holes were bored and he would put his stick in them to see if the depth was right. The shotsman would then come to fire and blow this roof down with explosives on the afternoon shift.

When you came into work the next day there was all this muck to clear away into the gob before you could start on the coal. The big stones were kept for the walls on both sides of the roadway – the pack as they called it. The walls had to be good on the roadsides as a support to the roof. And of course, you were advancing all the time so the tram rails into the stall had to be constantly lengthened. The collier and his assistant had to do all this.”

On Nationalisation of the Nation’s coal mines in 1947, Deep Navigation Colliery was placed in the National Coal Board’s, South Western Division’s, No.4 (Aberdare) Area, Group No.4, and at that time employed 282 men on the surface and 1,215 men underground working the Four-Feet, Six-Feet, Nine-Feet and No.4 seams. The manager in 1947/9 was H. Jarman and the under-managers S. Morgan & G.J. Jones. This colliery possessed its own coal preparation plant (washery) and was a depot for an NCB wagon repair workshop and road transport.

In 1949 the South Pit was closed as a production shaft to enable re-fitting of the guide rails and pit-bottom. This mammoth task was completed on Christmas Eve after eleven months of day and night work. 800 men had been transferred from the pit while the work was carried out, but the North Pit, during that period, produced 120,000 tons more than the whole pit did in 1947. In January 1950, the Coal magazine relayed an interesting story that dated back to the beginnings of the pit:

STORY OF A SHILLING

Behind the recent presentation of a shilling each to 120 aged Treharris miners lies the story of the generosity of two former colliery managers. The Deep Navigation Pits at Treharris were sunk in 1869, by Mr. Frederick Harris, a well-known Quaker, after whom the town was named. Later, a public hall was erected there, mainly by the workmen and officials taking up shares of £1 each, a number of which were held by Mr. William Stewart, and Mr. Forster Brown, two former managers at the colliery.

When they died, they each directed in their wills, that the interest on these shares should be divided annually among retired miners who had worked at the colliery when it was owned by Mr. Harris. The custom of distributing the interest, which amounts to £6 per annum, has continued for the past fifty years.

By 1954 only the Six-Feet and Nine-Feet seams were being worked and manpower had dropped to 190 men on the surface and 1,071 men underground, the manager was now W.J. Strong and the under-managers G. Jones & W. Burke. No one could suggest at the Merthyr inquest on the 19th of April 1955, on a 59-year-old underground engine driver why he left his workplace at the Deep Navigation Colliery, Treharris. The man, William David Williams, of Carpenters Cottages, Graig, Treharris, was found yards from the engine-house lying in the road with a fractured leg after two journeys of trams collided. He died a fortnight after being admitted to hospital. A verdict of accidental death was recorded.

In 1955 out of a total manpower at this colliery of 1,212 men, 599 of them worked at the coalfaces, this figure dropped during the latter 1950s to 553 men on the coalfaces in 1956, and 497 men on the coalfaces in 1958. To cover the shortage of manpower in 1956 major developments were carried out by contractors. The colliery management even went so far as to approach Merthyr Tydfil Council with a view to providing extra housing for the proposed expansion of manpower in the “long life pit.” The council agreed to build 70 houses near the colliery.

Sadly, there was no future for Lewis Evan Edwards, aged 52 years, of Bedlinog Terrace, Bedlinog, who collapsed and died at this colliery on the 17th of January 1956, or for Earnest Parker of Perrott Street, Treharris who was run over by a journey of trams on the 8th of March 1956 and died in hospital a few days later.

In 1961 this colliery was still in the No.4 Area’s, No.4 Group along with Merthyr Vale, Taff Merthyr and Trelewis Drift collieries. The total manpower for the Group was 3,398 men, while total coal production for that year was 1,042,000 tons, the highest group total in the Coalfield. The Group Manager was H.G. Evans the Area Manager was T. Wright and the colliery manager was V.D. Savage. Mr. Savage was still there in 1971.

In the early 1960s, the NCB invested £500,000 to re-organise the colliery, with part of this work being the installation of 1,540hp electric winders. The winding drum was of the bi-cylindrical, conical type. It could handle 40 men or 7 tonnes of materials per wind. Three underground bunkers with capacities of 100/200 and 400 tons were installed underground to speed up the conveyor system.

In the mid-1970s the NCB announced their intentions with regards to the collieries feeding power stations. They intended to concentrate production at three main units, one of them being the Taff Merthyr/Deep Navigation /Merthyr Vale Concentration Scheme. The reserves at Merthyr Vale were suitable for phurnacite production, and those at Taff Merthyr were suitable for power stations. With Deep Navigation, the western part of its take was suitable for phurnacite and the eastern part of the take for power stations. It was then proposed to wind only at Merthyr Vale and Taff Merthyr dividing the two types of coal between them. It was intended to retain DN for manriding and materials. If the scheme had been completed it would have cost £9.2 million and produced an annual output of coal of 930,000 tons between the three pits, with an output per manshift of 2.5 tonnes.

In 1976 the Crown Prince of Japan, Akihito, later to become Emperor of Japan, made an underground visit to this pit. A distinctly different visitor to Comrade Savkov of the USSR way back in 1942.

By 1978 there were ten miles of roadways in use including 5 miles of high-speed belt type conveyors. Output per manshift was 9.5 tons at the coalface and 2.3 tons overall for the colliery. 70% of Deep Navigation’s output was going to Aberthaw Power Station with the other 30% for general industrial usage. The NCB struck a medal to celebrate the centenary of this pit in 1979 and held an open day which attracted 2,000 visitors. The highlight was a ride to pit bottom.

By 1978 there were ten miles of roadways in use including 5 miles of high-speed belt type conveyors. Output per manshift was 9.5 tons at the coalface and 2.3 tons overall for the colliery. 70% of Deep Navigation’s output was going to Aberthaw Power Station with the other 30% for general industrial usage. The NCB struck a medal to celebrate the centenary of this pit in 1979 and held an open day which attracted 2,000 visitors. The highlight was a ride to pit bottom.

In December 1980, an outbreak of legionnaires disease caused 150 of the men to have blood samples taken with one man hospitalised.

This colliery had now hit a purple patch with Deep Navigation attaining its best ever annual profit at £2.6 million, and in May 1981 breaking its productivity record when the output for the week was 9,750 tonnes with 780 men.

In 1982 a new canteen was constructed at a cost of £93,000. In 1972/80 the manager was R. Elliot.

In 1983 this colliery was making a profit of £5.90 on each tonne of coal it produced. It had a manpower of 772. In 1977 the NUM Lodge Secretary was L. Jones, and in 1981 and 1984 it was B. Jones.

Another grand visitor was at the colliery on the 3rd of October 1983, Ian MacGregor was the chairman of the NCB, and took the opportunity to urge the miners to accept the offered pay rise, in case of circumstances may change ‘his generosity.’ He refused to comment on the future of the South Wales Coalfield but did state that there was no hope for the investment figures proposed by the NUM. He spent 2½ hours underground travelling on a new manriding system that had cost £250,000.

In March 1983, the NUM held a national ballot on whether to take strike action over pit closures, 68% of the South Wales membership voted for strike action, but overall in the UK’s pits only 39% voted that way and a national strike was abandoned. This was the vote that was later to cause a lot of confusion and bitterness at the start of the big strike.

By August 1990 British Coal announced that Deep Navigation was above target and safe from closure. They didn’t say for how long though, and Deep Navigation Colliery was closed by British Coal on the 29th of March 1991.

Based on the Nine-Feet seam this colliery’s coals were classed as type 201B and 202 Dry Steam Coking Coals, usually non-caking, low volatile, with a low ash content of around 5%, and a low sulphur content of Between 0.6% to 1.5%. Over the years its uses varied from steam raising in boilers for ships, locomotives, power stations, central heating etc., to foundry and blast furnace coke.

Some of the early fatalities at this pit:

- 26/71889 Timothy Davies, aged 22, collier, fall of the roof

- 8/1/1890 Samuel Double, aged 27, rider, run over by trams

- 8/1/1890 Edward Williams, aged 14, collier boy, fall of the roof

- 13/6/1890 Albert Miller, aged 14, labourer, run over by trams

- 26/6/1890 John Evans, aged 12, door boy, run over by trams

- 22/10/1890 William Goodwin, aged 22, collier, run over by trams

- 31/10/1890 Evan Davies, aged 36, labourer, crushed by wagons

- 9/4/1891 William Twaits, aged 24, haulier, fall of the roof

- 9/8/1892 George Chapman, aged 19, haulier, crushed by trams

- 17/8/1892 Edmund Morgan, aged 47, repairer, haulage accident

- 14/10/1892 John Owen, aged 37, haulier, strain

- 18/10/1892 Thomas Edwards, aged 24, collier, fell out of the cage

- 31/10/1892 Evan Jones, aged 49, pitman, struck by a stone

- 25/7/1893 Thomas Jones, aged 64, engineman, machinery

- 29/7/1893 Emanuel Jacob, collier, strain

- 29/9/1893 William Burrows, aged 36, labourer, fall of the roof

- 19/3/1894 Daniel Price, aged 20, repairer, caught in machinery

- 25/5/1894 George Owen, aged 48, collier, fall of the roof

- 3/9/1894 Morgan Davies, aged 24, assistant pitman. Fell off cage

- 15/9/1894 Thomas Davies, aged 53, repairer, fall of the roof.

Some Statistics:

- 1886: Output: 343,000 tons.

- 1887: Output: 316,324 tons.

- 1889: Output: 408,058 tons.

- 1892: Output: 281,484 tons.

- 1893: Output: 301,590 tons.

- 1894: Output: 415,765 tons.

- 1895: Output: 436,813 tons.

- 1896: Manpower: 1,846. Output: 452,241 tons.

- 1897: Output: 596,000 tons.

- 1899: Manpower: 1,496.

- 1900: Manpower: 1,533.

- 1901: Manpower: 1,689.

- 1902: Manpower: 1,621. Output: 327,000 tons.

- 1903: Manpower: 1,653.

- 1905: Manpower: 1,781.

- 1908: Manpower: 1,765.

- 1909: Manpower: 1,767.

- 1910: Manpower: 1,894.

- 1911: Manpower: 1,913.

- 1912: Manpower: 1,913. Output: 321,282 tons.

- 1913: Manpower: 1,880.

- 1914: Manpower: 1,946.

- 1915: Manpower: 1,946.

- 1916: Manpower: 1,946.

- 1918: Manpower: 1,946. Output: 307,238 tons.

- 1919: Manpower: 1,946. Output: 315,410 tons.

- 1920: Manpower: 1,946.

- 1922: Manpower: 1,946.

- 1923: Manpower: 2,062.

- 1924: Manpower: 2,090.

- 1927: Manpower: 2,182.

- 1928: Manpower: 2,223.

- 1929: Manpower: 2,200.

- 1930: Manpower: 2,246.

- 1932: Manpower: 2,200.

- 1933: Manpower: 2,190.

- 1934: Manpower: 2,276.

- 1935: Manpower: 2,238.

- 1937: Manpower: 1,918.

- 1938: Manpower: 1,868.

- 1940: Manpower: 1,820.

- 1941: Manpower: 1,920.

- 1942: Manpower: 1,880.

- 1944: Manpower: 1,840.

- 1945: Manpower: 1,816.

- 1947: Manpower: 1,497.

- 1948: Manpower: 1,529. Output: 403,000 tons.

- 1949: Manpower: 1,187. Output: 294,358 tons.

- 1950: Manpower: 1,181. Output: 316,994 tons.

- 1951: Manpower: 1,204. Output: 343,354 tons.

- 1952: Manpower: 1,232. Output: 365,767 tons.

- 1953: Manpower: 1,228. Output: 380,829 tons.

- 1953: Manpower: 1,244. Output: 434,000 tons.

- 1954: Manpower: 1,221. Output: 390,276 tons.

- 1955: Manpower: 1,212. Output: 400,297 tons.

- 1956: Manpower: 1,269. Output: 342,387 tons.

- 1957: Manpower: 1,296. Output: 369,040 tons.

- 1958: Manpower: 1,232. Output: 364,808 tons.

- 1960: Manpower: 1,141. Output: 327,000 tons.

- 1961: Manpower: 1,097. Output: 285,497 tons.

- 1962: Manpower: 1,089. Output: 299,909 tons.

- 1963: Manpower: 1,067. Output: 307,376 tons.

- 1964: Manpower: 1,040. Output: 342,055 tons.

- 1965: Manpower: 974. Output: 374,387 tons.

- 1966: Manpower: 1,002. Output: 391,436 tons.

- 1967: Manpower: 961. Output: 388,141 tons.

- 1968: Manpower: 992. Output: 369,483 tons.

- 1969: Manpower: 911. Output: 317,062 tons.

- 1970: Manpower: 884. Output: 323,526 tons.

- 1971: Manpower: 834. Output: 256,179 tons.

- 1972: Manpower: 817. Output: 263,272 tons.

- 1973: Manpower: 714. Output: 197,244 tons.

- 1974: Manpower: 811. Output: 317,870 tons.

- 1975: Manpower: 789. Output: 379,202 tons.

- 1978: Manpower: 800. Output: 375,000 tons.

- 1979: Manpower: 774. Output: 343,000 tons.

- 1980: Manpower: 789. Output: 343,210 tons.

- 1981: Manpower: 667.

- 1991: Manpower: 766.

Information supplied by Ray Lawrence and used here with his permission.

Return to previous page