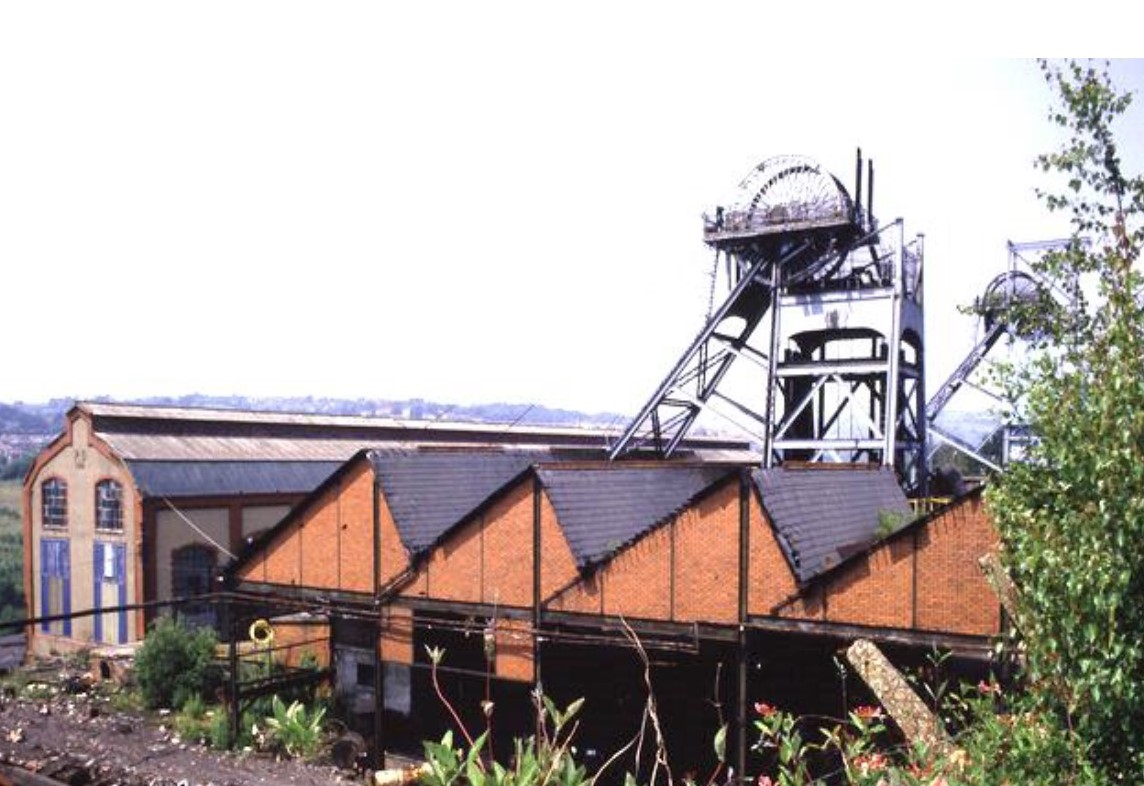

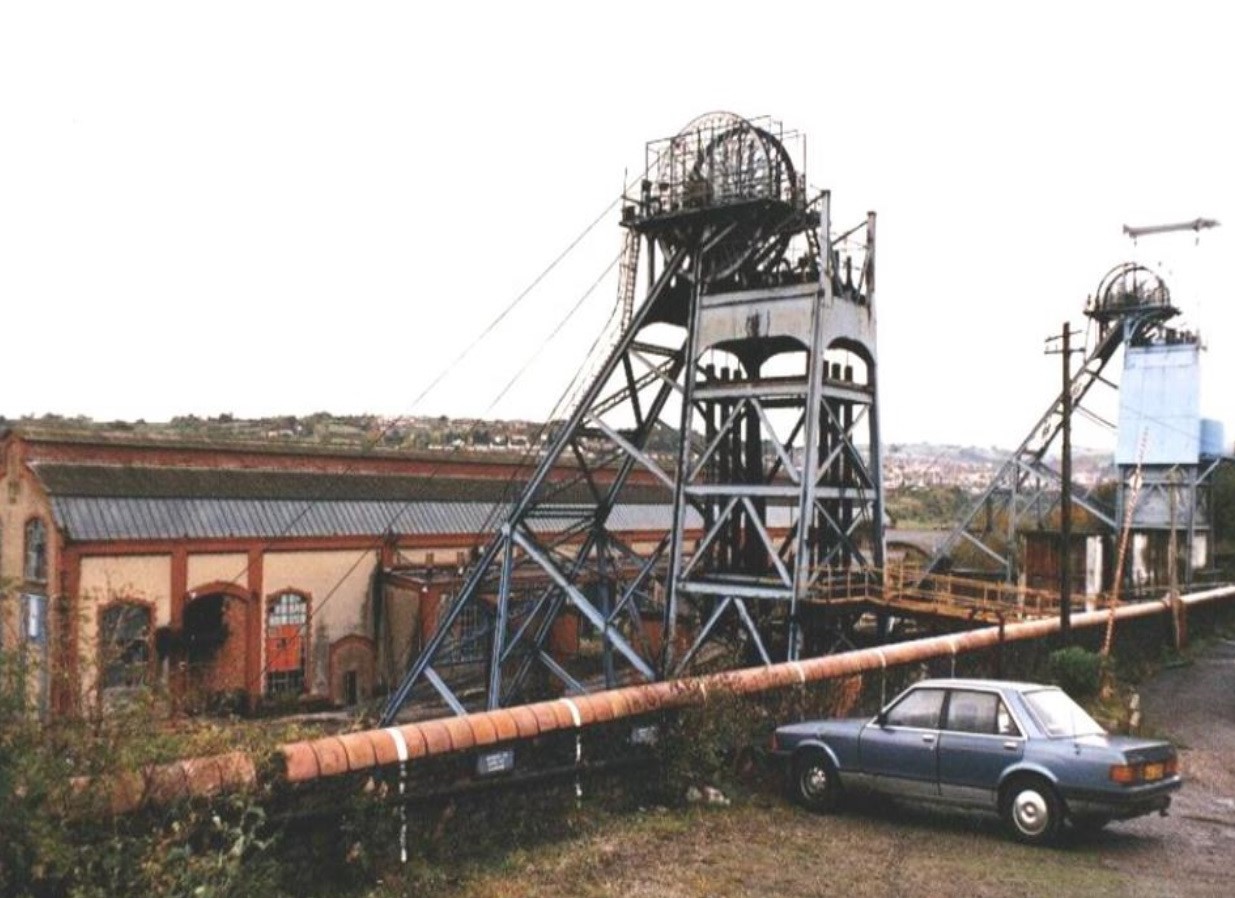

BRITANNIA COLLIERY

Pengam, Rhymney Valley (national grid reference 15789801)

NEW COLLIERY AT PENGAM – Important colliery developments are being carried out by the Powell Duffryn and Rhymney Iron and Coal Companies in the Rhymney valley, which bids fair to become a second Rhondda. Owing to the sinking of new pits Bargoed has been transformed in a few years from an obscure village to a town of 20,000 inhabitants. The next few years will witness the linking up of Bargoed with Pengam and Fleur-de-Lis, and the population within an area of three square miles will not be far short of 40,000 within five years.

The Powell Duffryn Steam Coal Company completed the Bargoed Colliery in 1901, and are now engaged in the sinking of Britannia pit, about a mile below the Bargoed Colliery and between the Gilfach and Pengam (Rhymney Iron Company’s) pits. Preparations for the Britannia Colliery were made in June 1910, and already the shafts have been sunk to a depth of 400 yards. It is anticipated that by Christmas the shafts will have attained a depth of 520 yards and that the total depth of 730 yards will be reached by May. The taking extends over several thousand acres, and the colliery will be one of the finest and best equipped in the country.

Large volumes of water have been encountered, no less than 100,000 gallons an hour having been dealt with by the pumps ranging from 500 to 800 h.p. The whole of the plant is operated electrically, the power is supplied from Penallta and from the gas engine station at Bargoed Colliery. There are two winding engines, each with its own Ligner set., The power is supplied at a pressure of 10,000 volts…each Ligner set has two starting dynamos, which will operate two winding motors on each winding engine when the plant is in operation winding coal. The Ligner wheels each weigh 33 tons and run at a maximum speed of 500 r.p.m.

This mine was sunk in 1911 in the heyday of both the South Wales Coalfield and the Powell Duffryn Steam Coal Company, which was a member of the Monmouthshire and South Wales Coal Owners Association. Britannia Colliery followed the sinking of the two other Powell Duffryn super pits in the Rhymney Valley; Bargoed Colliery in 1896 and Penallta Colliery in 1906.

This mine was sunk in 1911 in the heyday of both the South Wales Coalfield and the Powell Duffryn Steam Coal Company, which was a member of the Monmouthshire and South Wales Coal Owners Association. Britannia Colliery followed the sinking of the two other Powell Duffryn super pits in the Rhymney Valley; Bargoed Colliery in 1896 and Penallta Colliery in 1906.

It was bounded by Oakdale Navigation Colliery to the east, and the Pengam fault to the west and had a working area of around 4.5 square miles. Drawing on their vast experience in the planning and development of coal mines, Powell Duffryn set out the surface of the pit on the most efficient lines possible and installed the most modern winding techniques. It was located 1¼ miles south of Bargoed Colliery and 3 miles from Penallta Colliery.

This pit was the first in south Wales to be all electrically powered, with Powell Duffryn claiming that it was the first in the world to be all electric, and had no steam boilers. It was fed from Bargoed and Penallta Collieries by Powell Duffryn’s own grid which by 1916 had linked up to the Middle Duffryn power station nine miles away in the Cynon Valley.

It had five power lines servicing it from three different sources of power. The gas surplus from the coke ovens at Bargoed, the exhaust steam from the winders at Penallta and later on from the Middle Duffryn power station near Mountain Ash, It was also one of the first not to employ horses underground, all haulage work was done by conveyors or haulage engines. This wasn’t due to any concern about horses working underground, but to do with the shortage of horses created by the First World War.

The winding engines were designed to wind six tons of coal per minute. The drum was conical ranging from 14 feet to 22 feet with two 2,000 hp motors, with one being able to cope if the other failed. There were double-decked carriages in both shafts. Two shafts were sunk; the North Pit to a depth of 2,181 feet 3 inches, and the No.2 Pit to a depth of 2,202 feet to the Lower Nine-Feet seam.

The shafts were 21 feet in diameter with the South Pit being the downcast ventilation shaft and having rail guides for the carriage to travel on and the North Pit being the upcast ventilation shaft. It had rope guides for the carriage to travel on.

The sinking of the shafts started in February 1911 and was completed in September 1913 to a depth of 730 yards. It then took until August 1914 to complete the lodge rooms for pumping water up the pit, to make the pit bottoms and to drive out to open coalfaces. The pit bottoms were subject to a lot of pressure and it was decided to use 22 feet arches with three feet thick concrete blocks which had three feet of reinforced concrete with steel behind them. The floor was made of eight feet thick concrete.

The first of the steam coal seams, the Two-Feet-Nine or Elled was struck in September 1913. In January 1914 it started to develop the Red Vein which had a thickness of 48 to 54 inches.

On the 26th of August 1914 an inquest reported:

TIMBERMAN FATALLY CRUSHED.

Mr. W. R. Dauncey (deputy-coroner) held inquest at, Aberbargoed on Tuesday into the death Patrick Whitty (40), timberman. of Bryngwyn-etreet, Fleur-de-lis, who received fatal injuries at the Britannia Colliery, Pengam, on Saturday. The evidence showed that deceased was engaged in taking out part wall to make room for a girder when a fall of stone occurred, which almost completely buried him. Whitty was alive when extricated, and removed hospital, where he died next day. A verdict of “Accidental death was returned.

The Colliery Guardian dated the 20th of February 1915 reported that “raising coal has now commenced… at present about 200 men are employed and it is expected that number will gradually increase to 2,000.”

Another newspaper article in 1915 gave a glowing report for the future of the area:

WHAT PRIVATE ENTERPRISE: HAS ACCOMPLISHED.

With the population of the Valley steadily increasing—it is now about 100,000 —the housing question is admittedly a pressing one, and while local authorities are urged by the State not to embark upon an expenditure that can be deferred, it is gratifying to note that the erection of houses for the working classes is not by any means at a standstill. This is due to private enterprise. Most of the housing schemes were embarked upon previous to the outbreak of the war, and while the present crisis may slightly retard their progress they are now so far advanced that before long there will be less than three or four new villages in the valley. The greatest developments are taking place in the area of the Gelligaer Urban District Council, where schemes are in progress for the erection of over 1.500 houses.

The recent sinking of the Britannia Colliery at Pengam by the Powell Duffryn Company has been responsible for a considerable increase in the population in this vicinity, which will grow much more as the working of the colliery develops. cope with this increase the Welsh Garden Cities (Limited) have nearly completed what is known as Garden Village, comprising about 500 houses. This village is just out of the Gelligaer area, and comes in the Bedwellty Parish, being situated equidistant from Pengam, Blackwood, and Aberbargoed. It is being carried out on garden city lines, the houses being semi-detached. pro’ vision is made for shops, and schools the village is in the course of erection. In the immediate vicinity, on the road from Bedwellty to Pengam. sixty houses have also been erected by the District Council. The houses are rented as soon as they are completed. Britannia Hotel, to be erected here, applied for at the last licensing session but was considered premature. Again, to cope with the increase in population, caused by the development the Britannia Colliery, houses are being erected for the Powell Duffryn Company on the Tir-y-beth Estate between Pengam and Hengoed, and almost touching Fleur-de-Lis. This will be known as the Village, and, in conjunction with this scheme, the Gelligaer District Council are constructing a new main road from Pengam to Hengoed, which will be made through the new village. The houses will occupy about thirty acres of land and about fifty of the dwellings are completed. hotel licence here was considered premature. A third village that will come will occupy about 25 acres on the Cascade Estate. Pengam, bordering on the north side of the road from Gelligaer to Pengam. The Powell Duffryn Company have erected here houses, the site is ideal one. and slopes the south.

The summer of 1915 was full of little incidents at this pit:

- On the 30th of July, two trams fell back down the shaft, the other shaft was not available for winding so the men trapped underground had to walk 2.5 miles to the Bargoed shafts, then an electrical breakdown forced the company to lay off 1,000 men.

- On the 21st of August 1915, William Howells aged 17 years, and Henry Whitehead, aged 16, both colliers, decided to steal a pushbike which was chained up by the lamproom. The owner William Cox reported this to the police who caught Howells riding around on it. Howells reckoned that he bought it in Bedwas and Whitehead said that he bought it in Bargoed. They were fined 20 shillings each.

- Six sheep soon became the black sheep of the family when they strayed onto Britannia’s surface in May 1917. They were sold off by Powell Duffryn.

The word cowardice was bounced around in April 1916 when George Rutherford was accused of harbouring a deserter, his son, also George. George Junior signed on at Britannia as George Cannock but was spotted by an overman. The father when in court attested that he thought that the boy had been medically discharged from the Royal Irish Rifles. The court believed him and the case was dismissed.

On the 30th of April 1917:

CRUSHED BY CRANE. BHYMNEY VALLEY FOREMAN’S SPLENDID COURAGE.

Mr. James Evans, a foreman fitter the Britannia Colliery, Pengam, is lying badly burnt at the Cottage Hospital, Aberbargoed, the result of gallant devotion to duty in difficult circumstances. He was engaged in operations connected with moving a crane, weighing probably tons when a rope snapped twice in succession. Under all the attendant circumstances there was danger of explosion, and when the rope gave for the second time there was a rush for life on the part of the workmen who were engaged at that particular operation. But the brave fitter stood at the post of danger trying to avert what appeared inevitable, and all but escaped. Down crashed the crane, and the heroic foreman was pinned between the gigantic structure and a tram of burning ashes. Some time passed before was rescued, but even in his agony neither his courage nor his presence of mind deserted him. gave instructions as to what steps should be taken for his release, and these instructions greatly helped the rescue party. After being brought out of immediate danger was conveyed to the hospital. Mr. Evans lives detached house near Summerfield-terrace, Fleur-de-Lis, and is a brother-in-law of Councillor Edgar Davies, J.P., the leader of almost every patriotic and philanthropic effort that enterprising village. Mr. Evans has had experience as a marine engineer, and amid perils, sea acquired the presence of mind which, it believed, enabled him to save to lives of his fellow workmen at the colliery.

In 1918 there were 1,267 men working underground and 253 on the surface with the manager being W.E. Jayne. Mr. Jayne was noted for his sensible approach to industrial relations which paid off in that not one strike occurred during his tenure in 1918. Relations were not so rosy by February 1919 the South Wales Colliery Examiners Association members went on a week-end overtime ban following management’s refusal to implement a six-hour shift. In April of the following year when the company summarily dismissed a mechanic for joining the official’s union. All 2,000 men and officials went out on strike. This, according to the Daily Herald has created the strangest position in the history of the South Wales Coalfield where for the first time the officials, firemen and the Miners Federation act in unity.

On the 24th of February, a court case involved Britannia;

STARTLED BY WATCHMAN. WORKMAN’S DENIAL OF ASSAULT UNAVAILING AT BLACKWOOD.

An early morning incident on the railway line near the Britannia Colliery. Pengam. was detailed at Blackwood on Friday. when Lodwick Lest, (19), a blacksmith’s-striker, was annoyed for assaulting Tom James, watchman at the Britannia Colliery. Mr. W. Kenshole, Aberdare, was for the prosecution, defended by Mr. D. J. Treasure. Mr. Kenshole explained that owing to the danger to the men themselves of walking along the railway instead of along the road the company employed the complainant to keep the men off the line. The complainant stopped the defendant, who was walking along the line, but the defendant pushed by him. The watchman then followed him, and after he had ” clocked on ” again asked him for his name and address or his key number.

The defendant got in a fighting attitude and attacked the watchman with a heavy blow on the shoulder. In reply to Mr. Treasure. the witness denied that he was “officious and bumptious” in his manner. The defendant gave his version and said he was startled when the watchman jumped out on him first of all on the railway. He refused his name and address; until he “clocked on.” But gave the number of his key after “clocking on” to the complainant. who then caught him by the wrist and tried to pull him into the office. He refused to go into the office and pushed against the complainant. then went on to his work. No blow was struck at all. The defendant was fined 20 shillings.

The hardened attitude of Powell Duffryn towards the workmen can be shown when on the 19th of October 1921 some of the surface workers were not at their place of work when the pit hooter was blown to commence the shift. They were sent home and for good measure, the rest of the men were sent home as well. The men claimed that the hooter had deliberately blown earlier than it should have been.

The hardened attitude of Powell Duffryn towards the workmen can be shown when on the 19th of October 1921 some of the surface workers were not at their place of work when the pit hooter was blown to commence the shift. They were sent home and for good measure, the rest of the men were sent home as well. The men claimed that the hooter had deliberately blown earlier than it should have been.

One of the strangest incidents in the history of the Coalfield occurred on Tuesday the First of July 1924. John Sherway collected his lamp from the lamproom and simply disappeared, it was believed underground. Despite extensive searches of the current and old workings, he was never found. This was followed on Monday the 28th of July 1924 by the death in the colliery of Henry Smith after 50 years of working underground.

The South Wales Miners Federation Lodge at Britannia was quiet at the annual conference in 1925, not entering one proposal or amendment, whereas its neighbours at Pengam Colliery were involved in three and Bargoed were involved in four. At that time it was in the SWMF Rhymney Valley District which consisted of; Elliots, Bedwas, New Tredegar, Gilfach, Abertysswg, Bargoed Steam, Bargoed House coal, Pengam, Maesycwmmer, Groesfaen, Britannia, Mardy, Ogilvie, Barracks Level, Rhymney Enginemen, Gellyhaf, Rhymney Convenience. In 1964 the Rhymney Valley District merged with the Merthyr District and also pinched a few lodges from Monmouthshire.

On the 14th of April 1926, an inquest was told that James Elias Protheroe, aged 54 years and a collier, had died of a spinal injury that he received at Britannia Colliery nearly 10 years ago, what this case highlighted was that in all of the Rhymney Valley there was no official place to carry out post mortems. Mr. Protheroe’s was carried out on his kitchen table.

John Evans was a 46 year old repairer on the 9th of March 1928 when he was called to a fall to remove a large stone from the roadway. He moved the stone but commented that he felt “exhausted” He died on the 19th of March through natural causes claimed the inquest. On Tuesday the 20th of August 1929, night shift worker George Bennett was buried under a fall for four hours before his body could be extracted. It was in October 1930 and father and son Alfred and Gordon Wallace, both timbermen, were working together when a tram ran away, the son pushed his father out of the way but it appears his foot got caught and he was run over and killed. Then in October 1931 a huge stone, 9 feet 6 inches long fell on, and killed, Herbert Cooper aged 36 years and a married collier.

Pit head baths were installed at this colliery in August 1933 at a cost of £21,000. In 1934 the colliery employed 1,120 men underground and 170 men on the surface producing 400,000 tons of coal, the manager at that time was T. Thomas (he was there in 1927). H.S. Jayne was manager in 1938 when this pit employed 1,048 men underground and 195 men on the surface.

On the 10th of April 1938, two men were killed and another was seriously injured when repairing the compressed air pipes between Bargoed and Britannia collieries. Both John Henry Hammersley aged 56 a married man of Ruth Street, Bargoed, and a foreman boiler maker, and Roland Bertram Bond aged 23, and married, from William Street, Tiryberth died, while Frank B. Jones, aged 35, married and a fitter was injured.

In April 1938 the South Wales Miners Federation lodge at Britannia made a concerted effort to eliminate non-unionism at the pit. They checked that everyone had a contribution card and found two men who didn’t. The one man joined immediately but the other refused to join. The men threatened to strike on which the other man joined the union.

In 1943/5 the manager was C.H. Clarke. In 1934 the company was based at 1, Great Tower Street, London with the directors being; Edmund Lawrence Hann, Sir Leonard Brassey, Charles Bridger Orme Clarke, William Reginald Hann, Norman Edward Holden, Lord Hyndley, Sir Stephenson Hamilton Kent, Sir Francis Kennedy McClean and Evan Williams. The company secretary was Alfred Read. At that time it employed 15,260 men working in sixteen collieries who produced 4,780,000 tons of coal.

In November 1940 Charles Taylor Raynor aged 41 years and a married assistant repairer died under a roof fall.

On Nationalisation in 1947 Powell Duffryn handed control of this colliery over to the National Coal Board who placed in the South Western Division’s No.5 Rhymney Area, Group No.2, Britannia was selected as an initial and further training centre for recruits to the industry. At that time it employed 805 men underground and 146 men on the surface working the Seven-Feet and Upper-Four-Feet steam coal seams. The manager was T. Farrell, he was still the manager in 1949. It was in 1949 that racism reared its ugly head, although Britannia had accepted displaced workers from Europe, other collieries, including the so-called Little Moscow of Mardy had not, the Britannia men must have had second thoughts and decided to tender their notices for strike action due to the foreign workers having better transport facilities than them. The notices were later withdrawn.

Starting off the coalface was advancing 25 feet 6 inches every week and for the week ending the 29th of May 1954, the colliery produced its best output since 1930 when it wound up 10,038 tons of coal in that week. Production figures continued to improve and by 1955 the pit was averaging 2,368 tons of coal wound a day with the coalface advancing 37 feet a week giving a coalface output per manshift of 8.16 tons. The armoured face conveyor travelled at 145 feet per minute and the plough at 72 feet per minute so that the coal was rapidly taken away. Each cut was only two inches but on a 160 yard long face with a four-foot thick seam, 450 tons was produced each shift. In March 1955 the output per man shift was 29 cwts, the highest in the area, the North Pit worked two districts in the Seven-Feet seam by ploughs, and the South Pit worked two districts in the Four-Feet seam by AB15 cutters.

.In 1952 the first ‘rapid plough’ method of coal extraction in the South Wales Coalfield was installed in the 105 District of the Seven-Feet Seam.

In 1955 the first five miners in the Rhymney Valley to retire under the mineworkers pension scheme worked at Britannia. Together they had worked 284 years in the pits and included two brothers, William Walters aged 76 and Adam Walters aged 74 years.

Racism raised its ugly face in August 1954, when a Jamaican working at Britannia requested a transfer to Denaby Main Colliery in Yorkshire. The NCB had told, “now that the circumstances are known, it is not possible for you to come to Denaby Main Colliery, as the men will not accept either coloured or foreign nationals.” The NUM branch at Denaby Main was opined that they were not good enough workers, an attitude that sent shockwaves throughout the National Union of Mineworkers in Yorkshire.

Manpower had increased to 898 men underground and 173 men on the surface in 1954 when the pit produced 330,261 tons of coal. The manager was now J. Williams. Out of a total manpower of 998 men in 1955, 525 of them were working at the coalfaces, this figure remained fairly regular during the 1950s with 521 men at the coalfaces in 1956, 566 men in 1957, and 538 men at the coalfaces in 1958. In 1957 the Division carried out a survey of power-loading coalfaces and cited one at Britannia in the Seven-Feet seam which was 42 inches thick, the face was 510 feet long, employed 55 men and had an average daily advance of 66 inches, the best in the report for the Division. Coal cutting was by plough. Self-advancing coalface roof supports were introduced in 1959.

In 1961 the Rhymney Area controlled twelve pits which had a combined output of 2,769,348 tons, and a manpower of 11,537. Britannia Colliery was in No.3 Group along with Penallta and Bargoed and this group had a combined manpower of 3,337 and an output of 831,951 tons. In 1964 the NUM Lodge Secretary was G.H. Hodges. In 1969/71, K. Butcher was the manager, in 1972/5 it was T. Thomas and in 1976/9 it was D.J. Lewis. Towards the end of the 1960’s this colliery was in financial difficulties and was in danger of closing. It was producing 6,500 tons of coal per week and losing £0.46 on every ton of coal produced. Three-shift coal production was introduced and this did the trick by July 1968 it was producing 8,250 tons of coal a week and making a profit of £0.65 per ton of coal produced.

In March 1969 Lord Robens, the Chairman of the National Coal Board spent two hours on an underground visit to Britannia and announced that £150,000 would be available to open up a new seam that would hopefully increase production back up to 8,000 tons of coal per week. A new £100,000 coalface was opened in September 1969 and by December of that year, the colliery was making a profit of £6,000 per week and was top of the Rhymney Area’s productivity list with a face output per manshift of 260 hundredweights.

The North and South Pits at Britannia were separated by the 250 feet deep Britannia Overthrust geological fault. This tended to keep the workings of the two pits as separate until the mid-1970s when £950,000 was invested in linking the two sets of workings by driving an 800 metres roadway to carry all coal produced to the South pit, with a 915 metre drift to enable all men and materials to go through the North pit. At that time the colliery was working the Seven-Feet and Lower Four-Feet seams. If an industrial relations dispute could not be settled at the local level, assessors, consisting of NUM and NCB representatives would be called in. Such was the case in June 1979 when the men working on the L8 Coalface claimed extra money for working in wet conditions. This coalface was 220 yards long and six feet high with the area affected by the water being 70 yards long down the face from the supply road. They were not impressed with the claim and found very little water and agreed that the £1 per shift awarded by the manager was a fair payment.

In 1979 this pit was producing around 4,000 tonnes of coal a week with a coalface output per manshift of 5.1 tonnes and overall for the colliery of 1.4 tonnes. It had two coalfaces working. The NCB estimated reserves of 4.8 million tonnes. In 1980 the colliery was working the Five-Feet/Gellideg (Old Coal) seam with two coalfaces; the L5 with a length of 200 yards and a section of coal 71 inches and clod 12 inches, and the L6 also with a length of 200 yards and a section of; coal 74 inches and dirt 3 inches. Coal cutting was by two ranging drum shearers on each coalface and roof supports on the coalface were the self-advancing types. They were expected to produce 900 tonnes of coal per working day with expected output per manshift on the coalface at 11.43 tonnes, and overall for the colliery 2.16 tonnes. The saleable yield was 89% of the raised output.

Manpower deployment in 1981 was: coalface, 75 Development, 122 Others Underground, 111 Surface, 154. The manager at that time was D.J. Lewis. The NUM Lodge Secretary in 1977 and 1978 was G. Barton, and in 1981 it was Tommy Bowden.

In November 1980 the NUM Lodge at the colliery decided to accept the NCB’s proposal to reduce the manpower at the pit. The NCB reiterated that reserves of coal were minimal and this slimdown would extend the life of the colliery, although drivages to the Rhas Las and Red Vein had proved them to be unworkable. The men were not too happy about the slimdown but felt that they had no choice and accepted it. A month after the transfers of the men to other pits, the NCB stated that the colliery had to revert to two coalfaces to survive, but with the lack of men, this was impossible. Amongst much controversy, and a huge debate amongst the NUM culminating in an area conference, the Celynen North Colliery was allocated the remainder of Britannia’s reserves in 1983, and the colliery was closed as a production unit on the 8th of December 1983.

The colliery remained in use as a pumping station to protect Oakdale Navigation Colliery (it pumped up the shafts up to nine million gallons of water every day) until that colliery closed in 1989.

During the 1984/85 miner’s strike, 60 men continued to work at this colliery building an underground dam to protect the workings of Oakdale Colliery with NUM approval. In February 1981, the NCB withdrew its pit closure plan when faced with a series of strikes particularly in South Wales. Britannia was one of those threatened with closure, but Tommy Bowden, the NUM lodge secretary was pretty sceptical (with good cause) over the government. He concluded; “I am worried that closures will still take place but more slowly. Mrs. Thatcher’s tactic will be to try and buy us off, but we will not fall for it.”

Some Statistics:

- 1910: Manpower: 213.

- 1912: Manpower: 237.

- 1915: Manpower: 600.

- 1916: Manpower: 800.

- 1918: Manpower: 1,520.

- 1919: Manpower: 1,300.

- 1923: Manpower: 1,610.

- 1924: Manpower: 1,750.

- 1925: Manpower: 1,850.

- 1926: Manpower: 1,850.

- 1927: Manpower: 1,550.

- 1928: Manpower: 1,581.

- 1929: Manpower: 1,459.

- 1930: Manpower: 1,604.

- 1931: Manpower: 1,438.

- 1932: Manpower: 1,240.

- 1933: Manpower: 1,081.

- 1934: Manpower: 1,390. Output: 400,000 tons.

- 1937: Manpower: 1,232.

- 1938: Manpower: 1,243.

- 1940: Manpower: 1,107.

- 1941: Manpower: 1,145.

- 1942: Manpower: 1,062.

- 1943: Manpower: 806.

- 1944: Manpower: 951.

- 1945: Manpower: 806.

- 1947: Manpower: 951.

- 1948: Manpower: 906. Output: 256,065 tons.

- 1949: Manpower: 990. Output: 256,065 tons.

- 1950: Manpower: 958.

- 1951: Manpower: 926. Output: 244,000 tons

- 1953: Manpower: 947. Output: 391,000 tons

- 1955: Manpower: 998. Output: 341,146 tons

- 1954: Manpower: 1,071. Output: 330.261 tons

- 1956: Manpower: 1.085. Output: 402,921 tons.

- 1957: Manpower: 1.099. Output: 435,220 tons.

- 1958: Manpower: 1,112. Output: 398,033 tons.

- 1960: Manpower: 1,011. Output: 345,000 tons.

- 1961: Manpower: 1,007. Output: 330,938 tons.

- 1964: Manpower: 990. Output: 256,065 tons.

- 1967: Manpower: 1,157. Output: 313,147 tons.

- 1968: Manpower: 1,092. Output: 330,637 tons.

- 1969: Manpower: 1,074. Output: 366,562 tons.

- 1970: Manpower: 1,058. Output: 357,366 tons.

- 1971: Manpower: 978. Output: 222,629 tons.

- 1972: Manpower: 898. Output: 249,722 tons.

- 1973: Manpower: 851. Output: 140,808 tons.

- 1974: Manpower: 861. Output: 157,728 tons.

- 1975: Manpower: 831. Output: 221,119 tons.

- 1976: Manpower: 865. Output: 248,884 tons.

- 1977: Manpower: 836. Output: 157,442 tons.

- 1978: Manpower: 754. Output: 217,544 tons.

- 1979: Manpower: 722. Output: 181,018 tons.

- 1980: Manpower: 688. Output: 180,858 tons.

- 1981: Manpower 466.

This information was supplied by Ray Lawrence and is used here with his permission.

Return to previous page