Thomas Rhodes bought the Black Vein Colliery in December 1862 and then had to take out a mortgage for £28,000 to get started. Ten years later he sold it to the London and South Wales Coal Company but he was saddled with debts of £44,000 which the new company refused to take on. The deal was settled on the 29th of March 1873. The new company consisted of Edmund Hanney Watts, John Henry Johnson, James Duke Hill, Thomas Stokoe, Edward Stout, Henry Frederick Swan and William Millburn. They immediately started to modernise the concern and decided to sink new pits at the northern part of their mineral take. They struck the Black Vein on the 24th of August 1878 in the No.2 Pit, and amazingly seven days later the first tram of coal was wound. The new pits were linked to the Black Vein Colliery (it was now called the Old Black Vein) by a thousand-yard haulage plane and then 400 yards of level heading to the pit bottom.

It was in 1873 E.H. Watts formed the London and South Wales Colliery Company Limited, who realising that the (Old) Black Vein Colliery was coming to an end decided to sink the New Black Vein (Risca) Colliery just to the north of the old pits and eight miles to the north of Newport. It was planned to employ 1,050 men and 102 horses at the new pits with a daily output of 1,000 tons of coal.

The two shafts of the North Risca Colliery were commenced in September 1873, and was completed in June 1878 to the Black Vein (Nine-Feet) seam which was struck at a depth of 288 yards in the case of the downcast and to the Five-Feet seam at 320 yards for the upcast ventilation shaft both were 17 feet 6 inches in diameter. The Black Vein seam was the reason that the collieries of the southern Sirhowy and Ebbw Valleys were sunk. This seam averaged 3 metres in thickness and had a low ash content of around 6%. With a low sulphur content of between 0.6% to 1.5%, it was claimed to be the finest coking coal in the World.

The downcast shaft was split into two parts, one for coal winding and the other for pumping purposes. The No.1 pit steam winding engine was built by Messrs. Joicey & Company and it had two horizontal cylinders 36 inches in diameter with a stroke of six feet. The winding drum was 16 feet in diameter with the cage capable of carrying two trams on one deck. It was the first colliery in the South Wales Coalfield to use electric lighting at the pit bottom. Ventilation was by a steam-driven Guibal fan 40 feet in diameter and 12 feet wide producing 220,000 cubic feet of air per minute, and a Shiele fan 17 feet 6 inches in diameter producing 249,000 cubic feet of air per minute which was installed in 1893. The main haulage for underground work was steam-driven and sited at the surface with the rope boxed as it went down the shaft. It had two horizontal 14-inch cylinders with an 18-inch stroke and a five feet drum. Seven other compressed air operated haulages worked underground in the early days.

The sinking, development and early days of the colliery, as with every other colliery in South Wales, had the men’s wages controlled by the Sliding Scale Agreement. The deep depression in the iron trade throughout the world around 1870 forced the great ironworks of south Wales to either close or drastically reduce output. This in turn made the ironmasters look for new ways to make a profit.

In 1836 John Russell purchased the Waunfawr workings for £50,000 and opened the Black Vein Colliery (ST 2133 9461) on the site in 1841. In 1842 his workforce employed 15 boys under the age of thirteen years. One of them was Moses Moon aged eleven years; he was described as a carter and had been working twelve-hour shifts underground for the past two years. A girdle was passed around his body with a chain going between his legs and attached to the cart; he would then drag the cart along on all fours like an animal. This extract from the 1842 Royal Commission into Women and Children Working Underground and covers the Black Vein Pit. It gives a fascinating glimpse into the conditions and morality of the times.

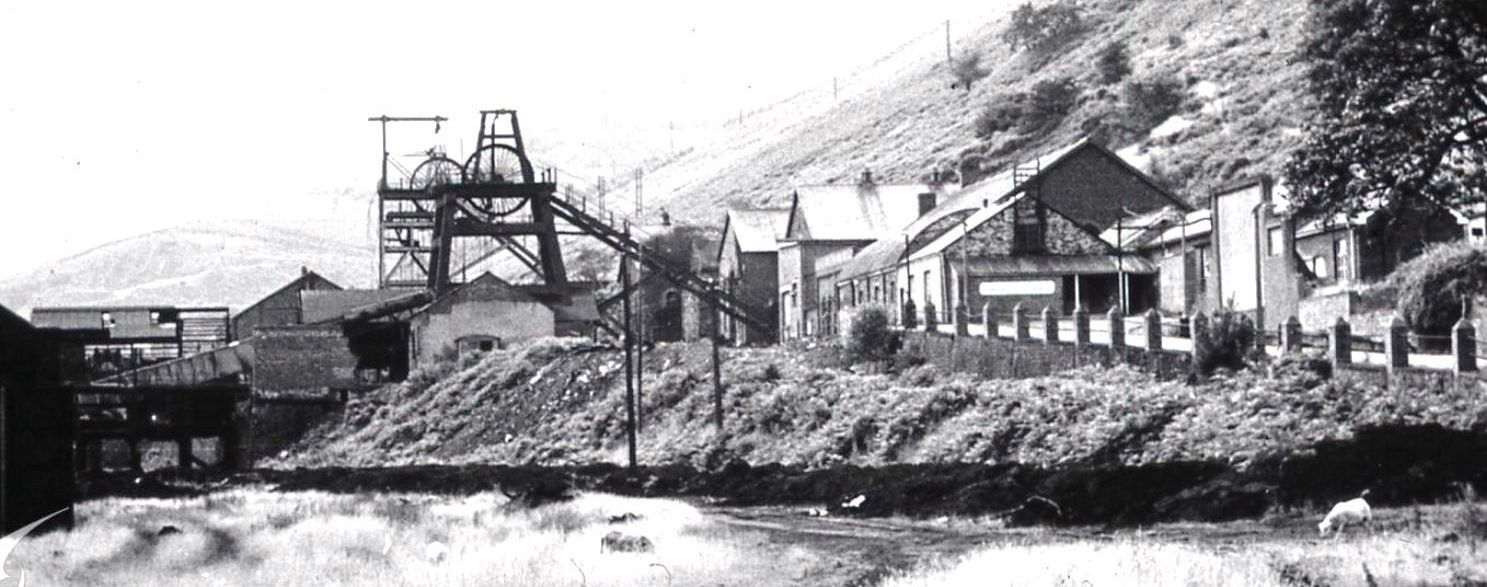

Risca New or North Pit 15th July 1880.

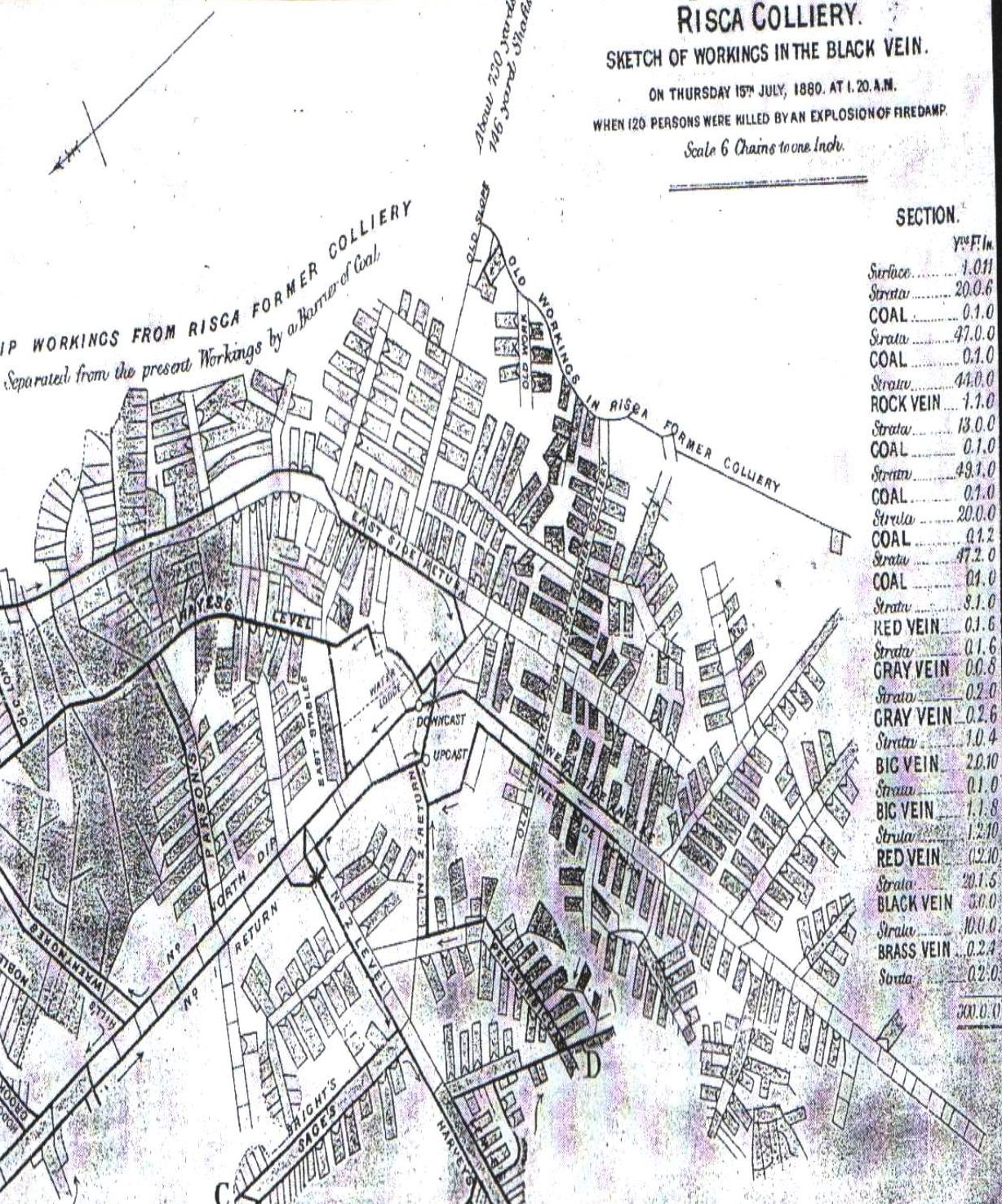

The New Risca Colliery was on the eastern side of the entrance to the Sirhowy Valley about one mile to the west of the outcrop of the South Wales Coalfield and about 1,260 yards to the north-west and in the same Black Vein seam as the Old Black vein Colliery. The existing colliery began work in June 1878 and was separated from the old colliery by an extensive barrier of unworked coal. The shafts were 298 yards deep and passed through the Rock Vein, which was 4 feet thick, at 113 yards, other seams and the Black vein, nine and a half feet thick at 287 yards and the Brass Vein, two feet thick, at 298 yards. The first seam which was worked at the colliery was the Black Vein. A section of the Black Vein showed 3 feet of coal, a small smooth parting, three feet six inches of coal, an inch of rubbish, two feet six inches of coal, three inches of rubbish and six inches of coal.

The strata dipped to the north of the shafts for about 100 yards then flattened at the working faces. The same seam was traversed in many places by transverse slanting and splits or cleavages. The coal was a hard steam coal, extremely fiery and very dry and dusty and contained streaks of soft coal that were even more firey.

The Black Vein was 298 yards from the surface but the principal workings were driven under the mountain which gave an additional height of 800 to 900 feet so that the depth of the workings from the surface was from 5 to 600 yards. The roof was, for the most part, shale but in some places, the shale was replaced by sandstone and it was near to one of these places that the explosion was thought to have originated. Only six feet of coal was got leaving three feet of coal as the roof in most parts of the mine and the other parts as the floor. The mine was subject to a lot of creep of the floor sides and roof. In the main intake, the No.1 North Dip, the floor had risen so much, that continual excavations to maintain the height had raised the floor level clear above the top of the vein in which it was originally excavated.

The Black Vein was 298 yards from the surface but the principal workings were driven under the mountain which gave an additional height of 800 to 900 feet so that the depth of the workings from the surface was from 5 to 600 yards. The roof was, for the most part, shale but in some places, the shale was replaced by sandstone and it was near to one of these places that the explosion was thought to have originated. Only six feet of coal was got leaving three feet of coal as the roof in most parts of the mine and the other parts as the floor. The mine was subject to a lot of creep of the floor sides and roof. In the main intake, the No.1 North Dip, the floor had risen so much, that continual excavations to maintain the height had raised the floor level clear above the top of the vein in which it was originally excavated.

The Risca Colliery had two shafts, a downcast, 293 yards deep and an upcast 287 yards deep both seventeen and a half feet in diameter. From the foot of the downcast shaft, two straight main roads, No.1 North Dip, which was the main intake and No.1 Return had been driven 80 yards to the north. From the No.1 North Dip a branch passed off to the right or East side to the “old Long Wall’ district and another further on, on the same side to ‘Hill’s and Wrentmore’s’ District. Further on towards the ends of these main roads, there was a third district, Crook’s, Brake’s and Dix’s. On the left or west side, another branch crossed the return and was called No.2 level which formed a fourth district comprising several sub-districts, Sage’s and Bright’s, Harvey’s and Lewis’, Paget’s and Penrhiwbicca. On the southwest side of the shaft two other new roads had been driven for 700 yards, the West Intake and the West Side Return. There were no working faces on these at the time of the disaster and had little bearing on the explosion. The four principal districts of the mine, Hill’s and Wrentmore’s on the east, the North Dip, the Old Long Wall on the east and the No.2 Level on the west were not entirely separate districts with the division made between them was by movable doors.

The colliery had been worked by double stall, two roads being driven 14 yards apart and the whole of the coal taken away between them and the space filled up with rubbish and small coal and pillars of coal, six yards wide left between the roadways separating one stall from the next. About 18 months before the explosion, longwall working had been adopted with the roads eight yards apart and the whole of the coal, except that for the roof and floor, extracted between the roads and the space between them filled. The long walls were worked away from the shaft and the consulting engineer, Mr. Foster Brown, considered that the system of driving advance headings to the boundary and working longwall towards the shaft was not applicable to the colliery. His view was supported by Mr. Wilkinson of Powell Duffryn and Mr. Green of Newport Abercarne. These men were all of the opinion that the great pressure on the roof would make it almost impossible to keep the necessary roads open. Mr. Joseph Dickinson pointed out that the longwall system was worked under similar conditions in the northwest of England and suggested that some of the dangers might be minimised by these longitudinal transverse walls to support the roof and gob.

There were 650 persons employed in the mine. The mine was worked on three shifts of eight hours each, two being work shifts and the third a repairing shift. There had been some objections to working two working shifts in a day and carrying on the faces too fast which did not allow the gas to drain away. About four men and two boys were employed to every 20 yards of the face. These men did their own stowing and timbering of the face. They undercut the coal and brought it down by wedges. The output of the colliery was about 600 tons per day. The workplaces were examined regularly by the firemen and overmen and from the evidence given at the inquest, the mine was worked by Clanny lamps and the firemen had Davy lamps.

Blasting was prohibited except in the main intakes, No.1 North Dip and No.2 Level. The shots were permitted only at night by the firemen or deputy overmen and it was restricted to the parts of the mine where the roof was rock. No shot had been fired on the night of the explosion.

Discipline and the ventilation in the mine were good and there had never been an accumulation of gas in the pit. The workings were regularly inspected. The agent, Mr. Llewellyn, inspected the workings on the first three days of each week and the Manager.

Three overmen, one for each district, attended each working shift and two attended the night repairing shift.

Ventilation was from a Guibal fan 40 feet in diameter and 12 feet wide. It was driven by a steam engine that had a 36-inch cylinder and a 36-inch stroke. There was also a spare engine of the same type. Both worked at a pressure of 40lbs. per square inch. There was a total of 132,830 cubic feet of air per minute and 46,110 cubic feet went to Hill’s and Wrentmore’s district and the North Dip, 33,600 cubic feet to the Old Long Wall district and 27,300 to the No.2 North Level. The stables and the new main roads on the southwest took about 37,700 cubic feet.

Timbering was very important due to the exceptional conditions in the mine and there had been complaints that there was an insufficient supply of timber in some parts of the mine but there had been no such complaints recently and there were few deaths from falls of the roof after the explosion which stood as a testament to the work of the colliers. The roads that were to be filled up to the top for about six yards from the end and to about 15 to 18 yards of the top, this being left open to allow some ventilation to get to the end until they were filled up. The filling consisted of the rubbish from the partings in the coal, the slack or small coal and the shale or rock got from the driving the headings, cutting the roofs, floors or walls of the main roads. It was never necessary to stow rubbish above ground. There was no evidence that the method of stowing the gob had anything to do with the subsequent explosion.

The explosion occurred about 1.30 a.m. on the morning of the 15th July and claimed the lives of 115 men. The full report can be found here. Other explosions had occurred in the past. 35 men died in 1846, 20 in 1853 and 141 in 1860. In 1882 another explosion killed 4 more men. On the 5th of March 1886, a minor explosion brought down the roof on father and son, John and 13 year old George Parry killing them both.

Some of the other fatalities at North Risca and the Black Vein since the opening of North Risca Colliery:

- 11/2/1882 An inquest was held at the Tredegar Arms, Risca-before the Coroner Brewer—on the body of John White, a collier, 26 years of age, who died on Saturday from injuries received on the previous day in the London and South Wales Colliery, at Risca. Deceased was working a hole in the face of the coal with a mandril, which was resting against his body, when a piece of coal fell out, and pressed the tool against him, inflicting severe internal injuries from which he died. The jury returned a verdict of Accidental death.”

- 12/5/1882 The body of Evan Price, a timberman at the Risca colliery, who was drowned by falling in the Sirhowy river, near the Full Moon, last Saturday week, during the severe gale and flood, was found in the river Ebbw, near Pontymister Works bridge, on Wednesday afternoon by a party of his fellow-workmen, who have been incessantly dragging the river since he was carried away. A melancholy satisfaction prevails at the recovery of the body of the unfortunate man, as it was feared he had been washed into the Bristol Channel.

- 20/4/1883 RISCA. On Thursday evening week, as William Terrell, a hitcher in the employ of the London and South Wales Colliery Co. was standing at the bottom of the shaft, a piece of coal fell upon his head and inflicted serious injuries. The injured man is about 24 years of age.

- 20/4/1883 Mr. W. H. Brewer on Saturday held an inquiry at the Tredegar Arms Inn, North Risca, as to the death of a collier named Thomas Thomas. The evidence showed that the deceased, who was employed at the North Risca Colliery, met with his death on Wednesday, the 19th instant, owing to a large quantity of coal having fallen upon him. He was taken to his home, and attended by Dr. Thomas, but died a few hours after the accident.—The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the evidence.

- 9/6/1883. An inquest was held on Monday at the Bridge Inn, before Mr Coroner Brewer, on the body of John Hart, a miner, aged 21, who was killed on Wednesday last, in the London and South Wales Colliery Company’s pit. Benjamin Phillips said he was at work near the upcast shaft, and saw deceased standing near. He had no special business in that portion of the pit at the time. observed him to suddenly stagger and fall, and perceived that a large knob of coal had fallen from an ascending train a distance of 100 yards or more onto his head. The deceased died almost directly afterwards. The jury found that the death was accidental.

- 13/3/1885 Late on Wednesday evening, as a collier named John Hart, employed at the London and South Wales Colliery Company’s pit, was passing beneath the shaft, a piece of coal fell on him from one of the ascending wagons, and crushed his head and shoulders, causing death. The deceased was a young man, only married three months, and much sympathy is felt for his widow.

- There was a strange fatality at this colliery on the 22nd of August 1887 at 7am, the under manager, Joseph Williams was “descending the shaft in a roomy cage, fell out for some unknown reason.”

- 3/3/1894. Thomas Smith and John Hufton were both aged 23 years and both colliers were killed by a roof fall. They estimated that the stone that fell weighed 5 or 6 tons.

- 12/9/90 On Thursday morning whilst Job Parsons, collier, of Pontywain, was following his usual work at the Risca Colliery, a fall of the roof took place, crushing him to death instantaneously. The deceased leaves a widow and several children.

- 18/11/1910. Francis Williams, a surface engine driver was cleaning and oiling when the engine moved and crushed his head.

- 13/12/1912. James Hiskins aged 33 years and living at Moriah Hill, Risca, was a labourer shunting waggons on the surface when he was run over and killed.

- 16/5/1914. Isaac Jones aged 72 years and a labourer, suffered a crushed thigh and internal injuries when hit by trams. He died seven months later.

- 11/6/1914. Trevor Symonds died under a roof fall in the Old Black Vein pit. It took them 26 hours to extract him.

- 9/5/1915. Godfrey Morgan aged 27 years and living in Tredegar Street, Crosskeys, died under a roof fall.

- 21/1/1916 Edward Charles Webster aged 33 years and a haulier, living at Tredegar Street, Crosskeys died under a roof fall.

- 1/8/1917. John Sibley was a Risca collier who enlisted in the army. He was killed in France.

- 18/4/1923 Frederick Redwood was trapped under a roof fall for 18 ½ hours Caught by one foot, to keep him alive a doctor fed him Brandy and water. He died in hospital from shock.

- 1/11/1929 Edward Thomas Stevens a collier died under a roof fall.

- 3/12/1930. Percy Gray, aged 25 years and living at Penrhiw, Risca. He was a timberman’s helper who was trapped under a roof fall. He died on the 15th December.

- 23/7/1934. Leslie Evans, aged 20 years of Railway Street was killed.

- 19/1/1939. David Lewis, aged 19 years and a dumper of Ty Isaf Park Avenue, Pontymister died under a roof fall.

- 14/4/1939. Stanley Jones, aged 25 years and a fireman living at Mill Street, Riscawas crushed to death by a falling stone.

- 20/4/1942. George Bridgman aged 55 years of Glenside, Crosskeys. Died under as roof fall. On 24/6/1942, the MP for Bedwellty raised in Parliament the case of nine rescuers who dug a man out of a roof fall and then brought him dead to the surface. As thanks, the company docked them, and the deceased half a shifts pay. No name was mentioned bar Risca Colliery so it was possibly this.

- 30/8/1951. Phillip Hoskins was run over and killed by a locomotive and thirteen wagons.

- 5/4/1957. Edwin Wilton George of High Street, Crosskeys was killed. Circumstances are not known.

April 1892:

RISCA. INTERESTING PROCEEDINGS AT RISCA COLLIERY.

On Saturday afternoon a Schiele-fan engine made by the Union Engineering Company, Manchester, was started by Miss Emily Watts, daughter of Mr E. H. Watts, of London (managing director of the Risca, Abercarn, National, and Blaenrhondda Collieries), in the presence of the mining engineer (Capt. G. W. Wilkinson, J.P., Messrs D. W. James, T. G. Clissol (mechanic), G. J. Broaches (manager). W. Smith-Williams, and a number of other officials. This engine is of the most modern description, being of a duplicate character, and in case of one part breaking down the other part could be set working at a moment’s notice. Mr Clissol (the company’s mechanical engineer), who superintended the whole arrangements, was presented, as a recognition of his activity and judgment in the matter, with a beautiful silver cup.

On the 8th of May 1892, United National Collieries Limited was formed with a capital of £400,000 in £10 shares to purchase “carry on, and work the collieries and works known as the National Colliery, and the Blaenrhondda Colliery…and the Risca and Abercarne Colliery.” (Western Mail, May 17th 1892). It was on the 1st of April 1902 that the Ebbw Vale Company was ready to welcome the Abercarn Colliery back into the fold, and they again took over control of the colliery. The lessee’s had complained that they were unable to make a profit with the current rent levels and tried to get the rent reduced. The Ebbw Vale Company refused to lower the rents and regained a colliery that they estimated was worth £150,000 for £9,000 (the cost of the new plant installed by the lessee’s). They estimated that there were 25 years of work at a weekly output of six to seven thousand tons of coal. This return to the Ebbw Vale fold was not without its human costs with men losing their jobs. The Moore’s level in the Black Vein seam had reached the boundary of Abercarn’s take and was working outside of the Abercarn mineral lease area and into the Risca mineral lease which was still owned by the United National Collieries. The Ebbw Vale Company had no rights to this coal so the district had to close. Manpower dropped from 1,150 in 1901 to 847 in 1902.

There was a new manager in 1906, John Kane, aged 27 years, Kane joined the company as a door boy at National Colliery, Wattstown studied hard at Cardiff University and was appointed surveyor at that pit in 1905. His actions and heroics at the National Colliery explosion held him in high regard, and he was drafted in by the Government to advise on rescue operations at Senghenydd. He became manager at Risca in 1905 with Mr. Llewellyn becoming General Manager for the company.

The people of Risca and Abercarn had erected six triumphal arches between Risca House and Abercarn to celebrate the marriage of E.H. Watts, and on meeting them at Abercarn station with bands, bunting and speeches welcomed them to the district.

In 1892 the London and South Wales Colliery Company Limited was reformed into United National Collieries Limited. During that year it was claimed that Risca was the first pit in South Wales to have electric lighting on both pit top and pit bottom.

Also in 1892, the Five-Feet seam at the Old Black Vein had been closed due to difficult trading conditions for 14 months until reopened in August 1893. The new company carried out limited work in the Old pit, in 1905 it employed 150 men, in 1908 the Old Pit employed 352 men and was managed by Ivor Llewellyn, with both the Old and the New Risca’s employing 2,247 men in 1913, the manager at that time was S.H. Williams. The Old Pit employed 530 men in 1915/6. The Old pit was still listed in 1935.

In 1894 Abercarn Colliery was leased out to the United National Collieries Limited. It was on the 1st of April 1902 that the Ebbw Vale Company was ready to welcome the Abercarn Colliery back into the fold, and they again took over control of the colliery. The lessee’s had complained that they were unable to make a profit with the current rent levels and tried to get the rent reduced. The Ebbw Vale Company refused to lower the rents and regained a colliery that they estimated was worth £150,000 for £9,000 (the cost of the new plant installed by the lessee’s). They estimated that there were 25 years of work at a weekly output of six to seven thousand tons of coal. This return to the Ebbw Vale fold was not without its human costs with men losing their jobs. The Moore’s level in the Black Vein seam had reached the boundary of Abercarn’s take and was working outside of the Abercarn mineral lease area and into the Risca mineral lease which was still owned by the United National Collieries. The Ebbw Vale Company had no rights to this coal so the district had to close. Manpower dropped from 1,150 in 1901 to 847 for 1902. In 1892 United National Collieries Limited took control of both collieries, the Five-Feet seam at the Old Black Vein had been closed due to difficult trading conditions for 14 months until reopened in August 1883. Controlling interest of this Company was gained by the Ocean Coal Company in 1928. Both companies carried out limited work in the Old pit, in 1905 it employed 150 men, in 1908 the Old Pit employed 352 men and was managed by Ivor Llewellyn, with both the Old and the New Risca’s employing 2,247 men in 1913, the manager at that time was S.H. Williams. The Old Pit employed 530 men in 1915/6. The Old pit was still listed in 1935. UNC was swallowed up by the Ocean Coal Company in 1926.

In 1880 the company proudly announced that they were to provide a reading room with books and magazines, chess and draughts, along with a private meeting room for free to its workers, plus non-alcoholic refreshments for a small fee. In September 1884 there were 170 men and boys working in the Old Black Vein Pit, and they were given the stark choice, accept a pay cut of 4 pence per ton we will shut the pit.

In 1896 this pit employed 840 men underground and 168 men on the surface working the Black and Lower Black Vein seams. The manager was G.W. Wilkinson. It was in 1896 that tentative probes were made amongst the men to form a union. It was decided not to affiliate with anyone but to keep it local until enough men join then they would review it. An interesting indication of the attitudes of the times was that in 1900 the Owners took seventeen men to Court for absenting themselves from work for three days without permission. They were fined £1 each. United National Collieries were members of the Monmouthshire and South Wales Coal Owners Association and fully enjoyed the benefits of that association, particularly the compensation for loss of output due to disputes with the men. The H.M. Inspectors report for 1902 stated that at this colliery; “workmen stopped work for some days on two or three occasions in consequence of their examiners, under General Rule 38, finding firedamp in one very large district. They reported to HMI resulting in the matter being rectified … This is the first instance which has come to my knowledge of the men have proved themselves in this way practically alive to their own safety.”

The explosion at Universal Colliery further highlighted the dangers of gas emissions in the south Wales Coalfield and in this colliery the men became understandably nervous. On the 1st of November 1913, they embarked on a one week strike over the fear of gas at the pit. On the 19th of July 1918 until the 23rd of August 1918 a fire in the west side workings of the Old Black Vein kept 2,000 men out of work in both pits.

In 1913 Risca Colliery was managed by S.H. Williams and employed 1,117 men, he was still the manager in 1915. In 1916 it was managed by T. Jenkins and employed 1,717 men.

A bit of good news at last. In 1930 the Central Miners Welfare Committee paid for a pithead baths to be constructed at this colliery. There were 542 men working there at the time but the baths were built to accommodate 1,200 and cost £14,382 to build.

Depression or not, most of 1931 was spent on strike over another dispute, this time over a colliers price list for a new coalface. The pit was idle for ten months and restarted on the 4th of December 1931.

In 1923 the manager was A. Terrell and in 1927/35 it was H.E. Marshall. In 1928 United National Collieries came under the control of the Ocean Coal Company, who in 1935 employed 270 men on the surface of the mine and 531 men underground at Risca working the Big (Four-Feet), Black Vein and Rock Vein seams. This colliery had its own coal preparation plant (washery), coke ovens and a by-product plant. The manager at that time was H.E. Marshall. In 1934 the directors of United National Collieries were Lord Davies, Thomas Evans, William Phillip Thomas, Alexander Jaffray Cruikshank, Alfred Ernest Yarrow, Herbert Frank Perkins, Sir Henry Webb and Michael Arthur Henderson. The company secretary was A.W. Dalton. At that time it controlled three collieries that employed 3,277 men who produced 1,750,000 tons of coal.

In 1935 the colliery employed 683 men underground and 122 men on the surface, the manager now being F. Wilcox. Mr. Wilcox was still manager in 1938 when it employed 713 men underground and 133 on the surface. In 1943 it was managed by PSH Jones who employed 578 men working underground in the Meadow Vein, Three-quarter, Old Coal, Black Vein, Elled and Big Veins and 142 men working at the surface of the mine. In 1938 the manager was G. Jones and in 1945 the manager was H. Davies.

On the 14th of May 1942 a man was killed under a fall at this colliery. At great risk to themselves, nine men recovered the body and then took him home. Their reward was to be docked half a shifts pay along with the dead man. This action caused such a row that it was raised in Parliament.

In 1943 this pit employed 582 men underground working the Lower Black Vein and the Big Vein seams and 173 men at the surface of the mine.

On Nationalisation of the Nation’s coal mines in January 1947, Risca Colliery was placed in the National Coal Boards, South Western Division’s, No.6 (Monmouthshire) Area, Group No.3, and at that time employed 531 men underground out of a total workforce of 801. The manager at that time was still J.H. Davies.

In March 1953 the men at Risca Colliery showed their generosity to others; with the surplus money made from the colliery canteen, five specially equipped baths suitable for use by disabled workmen were opened, a television was purchased for the Institute and at a supper at Crosskeys Girls Club cheques were given to various organisations. In 1954, 137 men were employed on the surface and 619 men were employed underground working the Lower-Black Vein (Five-Feet/Gellideg) seam. The manager was now A.E. Craddock. In 1955 out of total colliery manpower of 776 men, 374 of them worked at the coalfaces, In December 1955, between November 11th to 14th 700 men stopped work following allegations that a deputy swore at a conveyor shifter. The future looked bright in 1957 when £83,316 was allocated to the colliery to develop the Meadow Vein. This was an important boost for the colliery.

In 1956 this coalface figure was 366 men, in 1957 it was 356 men, in 1958 there were 328 men working at the coalfaces in this colliery, and in 1961 out of a colliery total of 478 men, 170 of them worked at the coalfaces. In 1961 this colliery was in the No.5 (Rhymney) Area’s, No.2 Group along with Nine Mile Point and Wyllie Collieries. The total manpower for this Group was 1,885 men, while total coal production for that year was 472,073 tons. The Group Manager was E. Jones, and the Area Manager was G. Tomkins. The National Union of Mineworkers Lodge Secretary at this pit in 1964 was Keith Griffiths. The M6 and M10 coalfaces were part production faces with their primary function being training new colliers.

In early 1959 the pit was working under Islwyn Road, Wattsville and subsidence from those workings badly affected around fifty houses with cracks in the ceilings and walls and ill-fitting doors, it was so bad that one house had to be demolished. Surprisingly the residence accepted this inconvenience stoically believing that the NCB was doing everything it could to repair the damage.

In June 1962, 21 miners at this colliery staged a 33-hour stay down strike over the NCB’s decision to take power loading from the colliery which they viewed as a precursor to closure.

The NCB reported that this colliery lost £106,000 in the year ending April 1965, equivalent to 90 pence per ton. They continued to state that the economically workable reserves of coal were coming to an end and the men’s interests would be best served by being transferred to other pits. It was originally intended to close Risca on the 20th of May 1966 but this date was deferred until the 9th of July 1966. The shafts were filled in June 1968.

Some Statistics:

- 1880: Manpower: 800.

- 1889: Output: 346,199 tons.

- 1894: Output: 405,071 tons.

- 1896: Manpower: 1,006.

- 1899: Manpower: 1,148.

- 1900: Manpower: 1,201 plus 106 at Black Vein.

- 1901: Manpower: 1,226.

- 1902: Manpower: 1,252.

- 1903: Manpower: 1,452.

- 1905: Manpower: 1,593 with Old Black Vein.

- 1907: Manpower: 1,649 plus 261 at Old Black Vein.

- 1908: Manpower: 1,647.

- 1909: Manpower: 1,667 plus 332 at Old Black Vein.

- 1910: Manpower: 2,114 with Old Black Vein.

- 1911: Manpower: 1,911 with Old Black Vein.

- 1912: Manpower: 1,792 plus 542 at Old Black Vein.

- 1913: Manpower: 1,117.

- 1915/6: Manpower: 1,717.

- 1918: Manpower: 2,084.

- 1919: Manpower: 2,016.

- 1923: Manpower: 2,033. Output: 450,000 tons.

- 1924: Manpower: 1,828.

- 1925: Manpower: 1,691.

- 1927: Manpower: 1,350.

- 1928: Manpower: 1,516.

- 1929: Manpower: 1,250.

- 1930: Manpower: 1,468. Output: 450,000 tons.

- 1931: Manpower: 1,350.

- 1932: Manpower: 800.

- 1933: Manpower: 790.

- 1934: Manpower: 626.

- 1935: Manpower: 801.

- 1937: Manpower: 906.

- 1938: Manpower: 1,047.

- 1940: Manpower: 1,020. Output: 300,000 tons.

- 1941: Manpower: 1,130.

- 1942: Manpower: 1,070.

- 1945: Manpower: 755.

- 1947: Manpower: 710.

- 1948: Manpower: 661. Output: 175,000 tons.

- 1949: Manpower: 665. Output: 196,000 tons.

- 1950: Manpower: 665.

- 1951: Manpower: 712. Output: 179,660 tons.

- 1953: Manpower: 753. Output: 219,000 tons.

- 1954: Manpower: 756. Output: 195,825 tons.

- 1955: Manpower: 776. Output: 204,506 tons.

- 1956: Manpower: 763. Output: 188,137 tons.

- 1957: Manpower: 749. Output: 177,641 tons.

- 1958: Manpower: 705. Output: 170,925 tons.

- 1960: Manpower: 500. Output: 133,542 tons.

- 1961: Manpower: 478. Output: 104,249 tons.

- 1962: Manpower: 483.

This information has been provided by Ray Lawrence, from books he has written, which contain much more information, including many photographs, maps and plans. Please contact him at welshminingbooks@gmail.com for availability.

Return to previous page