Oakdale Colliery 1989

Copyright © Stephen Thomas and used with his kind permission

Oakdale, Sirhowy Valley (ST 1848 9898)

Details of Waterloo Colliery can be found here

By the beginning of the 20th Century, the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company had turned to coal production in a big way, their coal reserves at the northern end of the Sirhowy Valley were rapidly becoming exhausted so they decided to probe the untapped steam coal seams of the Lower and Middle Coal Measures in the central Sirhowy Valley. In 1906 they negotiated for the lease of the mineral rights for the lands between Hollybush and Ynysddu.

For Oakdale Colliery, 2,700 acres were leased and included the Mynyddislwyn seam which was to be worked for house coal from the Waterloo level, the Brithdir seam which was to be worked from the Waterloo pit and the seams of the Middle and Lower Coal Measures which were to be worked from the North and South Pits.

They estimated that it would take 680 yards of sinking to hit the main seam to be worked and when the pit was up and running it would produce 2,500 tons of coal a day with manpower of between 3,000 and 3,500 men. The most advanced equipment for winding was ordered from Markham’s works at Broad Oaks Iron Works at Chesterfield. The company formed to run the colliery, the Oakdale Colliery Company was wholly owned by the TIC which would be the parent company and the means of finance. Unusually for those days, no extra shares were sold with the whole operation financed from TIC profits.

Profits in recent years were: 1901 £124,267.

- 1902 – £ 84,691.

- 1903 – £ 79,813

- 1904 – £ 61,978

- 1905 – £ 66,613

- 1906 – £ 80,960

In 1907 they had made a profit of £178,630 and paid out a 10% dividend, but in 1908 the profit was £91,776 with a 5% dividend paid out, this on top of the £50,000 or so set aside for the Oakdale project each year. All management of the new company were to be TIC men including Sir Charles McLaren chairman, the TIC managing director and chief salesman, Wilson Taylor, A.S. Tallis the general manager, Messrs. Scott and Leggett electrical engineers and W.C. Hepburn who was in charge of the sinkings.

Along with the sinking of the colliery at Oakdale the company built a village on a nearby plateau, which according to a TIC booklet:

Comprises of some 500 workmen’s houses, each having a bathroom. (by 1946) The village has all the amenities for recreation – Institute, Picture House, playing fields, bowling green and tennis courts etc. The remaining workmen live within a few miles of the colliery and travel by bus.” An article in the Coal News dated September 1950 reported that the colliery was; “sunk in the most beautiful part of the valley the colliery fits into its background. The pit yard is approached by an avenue of trees, and there’s a rose garden designed by the well-known landscape artist, John St. Bodvan Gruffydd. The colliery has one disadvantage: there’s a steep drop from baths to pithead, with more than a hundred steps, and an escalator has been suggested and is under consideration…In 28 years Oakdale has had only one one-day strike – a tribute to management and men.

The ceremony of cutting the first sod for the site of this colliery was carried out by the wife of Arthur Markham (1866-1916) a TIC Board Member and Liberal MP for Mansfield in Nottinghamshire. It is possible that the colliery was named after his works in Nottingham which was called the Oakdale Engineering Works.

The sinking was started in 1907 and was completed in 1911 with three shafts being sunk; the North (upcast ventilation) and South (downcast ventilation) pits to the steam coal seams of the Lower and Middle Coal Measures, and the Waterloo Pit to the Brithdir seam of the Upper Coal Measures. The first colliery manager was Major W.C. Hepburn who was replaced in 1913 by David Evans. Hepburn then became the colliery agent until 1927.

The South Pit was the downcast ventilation shaft and its headgear was 76 feet high to the centre of the sheaves which were 20 feet in diameter. It was of a steel lattice design by Rees and Kirby. The shaft was 21 feet in diameter and sunk to the Upper Rhas Las (Upper Nine-Feet) seam which was found at a depth of 680 yards. Simultaneous decking was used at pit top and bottom with originally double-deck cages carrying two trams each, with each tram carrying 25 cwts of coal. The winding engine on this pit was made by Markham and Company and had 36-inch cylinders with a stroke of seven feet. The drum was semi-conical rising from 17 feet to 27 feet 6 inches diameter (this drum and new brake gear was installed in 1946).

The North Pit’s headgear was also lattice design and made by Rees and Kirby but was 83 feet high. Initially, it was used mainly to transport men and materials and had single deck carriages. Again the winding engines were by Markham and Company with 36-inch cylinders with a seven feet stroke and a semi-conical drum 16 feet to 28 feet in diameter. The carriages were single deck carrying two trams at a time.

The headgear at the Waterloo pit was steel lattice and 55 feet high. The winding engine was made by guess who? It had 22 inch diameter cylinders which had a 5-foot stroke. The drum was semi-conical ranging from 10 feet to 15 feet in diameter. This pit was sunk in 1908 to replace the old Waterloo Level to the Brithdir seam, which it found at a depth of 286 yards.

The Waterloo pit was a downcast ventilation shaft, 17 feet 6 inches in diameter and had a winding capacity of two trams of coal/material per wind giving 97 winds per hour. It worked the Brithdir seam at a section of 43 inches.

In July 1908 the company stated that the two steam coal shafts had already been sunk to between 300 and 350 feet and it was estimated that the Black Vein coal would be reached at a depth of 680 yards and the Brithdir seam at a depth of 300 yards. Sulzer centrifugal pumps having a pumping capacity of 20,000 gallons per hour have been installed and are now in use, and orders have been placed for the delivery at an early stage of more pumps capable of dealing with 80,000 gallons per hour. At this colliery all the electricity needed for the pumping, hauling and ventilation will be generated by means of the exhaust steam from the winding engines, but the turbine plant is so designed as to make it adaptable for use either with the exhaust or high-pressure steam. Each generating set will be a duplicate of the other, and the erection of a powerful set of winding engines, made by Messrs. Markham & Co., of Chesterfield, is now nearing completion.

The permanent winding gear will be used for the sinking operations. Headgears of steel and wood have been erected, and the boiler plant consists of six boilers, each capable of generating 20,000lb of steam per hour fitted with forced draught, mechanical stokers, coal bunkers. In the 38th AGM of the company in June 1911 the chairman reported that; ”Oakdale had for some years been a source of considerable expenditure, but he was glad to say that they could see an end of their operations. They had in that colliery no less than 30 feet of workable coal in seams of not less than 2 feet, thickness. That meant a very extended life for the Tredegar colliery.”

In order to compensate for their depth (they were amongst the deepest in the Coalfield) the steam coal shafts were constructed with the largest diameter of any shafts in the Coalfield (21 feet), with double-deck carriages being installed in the South Pit to enable five tons of coal to be brought up per wind. This was the main winding shaft and could do 50 winds per hour. The North shaft could do 55 winds per hour but with a two tram capacity (24 cwts per tram). The Waterloo pit could also wind two trams per trip and 97 winds per hour.

Oakdale Colliery had a difficult start to life when it encountered adverse geology in the pit-bottom area, in desperate attempts to open up the pit from the pit bottom timbers more than 18 inches thick were used to try and prevent the roof from coming down and blocking the roadways. What they had thought was the Rhas Las seam turned out to be an unworkable rider coal. It wasn’t until a roof fall in that seam exposed the ‘proper’ seam above it that they realised their mistake. The problem that now faced the owners was that the pit bottom was 30 feet lower to work the newfound seam. The answer was to create a new pit bottom in the North shaft thirty feet higher than the old one.

Oakdale Colliery had a difficult start to life when it encountered adverse geology in the pit-bottom area, in desperate attempts to open up the pit from the pit bottom timbers more than 18 inches thick were used to try and prevent the roof from coming down and blocking the roadways. What they had thought was the Rhas Las seam turned out to be an unworkable rider coal. It wasn’t until a roof fall in that seam exposed the ‘proper’ seam above it that they realised their mistake. The problem that now faced the owners was that the pit bottom was 30 feet lower to work the newfound seam. The answer was to create a new pit bottom in the North shaft thirty feet higher than the old one.

The original intention of working the coal seams from the bottom one up was also abandoned over the fear of flooding in the bottom seam, the Five-Feet/Gellideg or Old Coal, this was highlighted when the neighbouring Crumlin Navigation became flooded when they struck the Old Coal seam. The original intention of working the coal seams from the bottom one up was also abandoned over the fear of flooding in the bottom seam, the Five-Feet/Gellideg or Old Coal, this was highlighted when the neighbouring Crumlin Navigation became flooded when they struck the Old Coal seam. It became apparent that with all the problems that they were encountering, the men at the top needed to be very experienced and able to adapt to the conditions, Mr. Hepburn was shoved upstairs and David Evans, the manager of Ty Trist Colliery, brought in to sort it all out. He was fortunate that technology was by now catching up with the problems of roof supports in the form of ready-to-measure steel arches (rings) they started to replace the old timber supports in weight affected roadways, with there no need to saw and trim timber to fit what was required, and no further need to use brickwork in tricky places steel arches were also cost-effective, especially as they were made in the Tredegar Works of the TIC. The colliery was soon working the right seams and in The colliery was soon working the right seams and in 1913 employed 714 men.

On the 11th of December 1914:

MATCHES IN THE MINE. SEVERAL COLLIERS FINED BLACKWOOD.

There were several prosecutions under the Mines Act at Blackwood Police court on Friday. Owen Phillips (16), collier. Penmaen, and William Turley (15) were each fined for having a match in their possession at Oakdale and were fined £2 each. the Oakdale Colliery, while another collier, William Mathias (27), was fined £2 for having three matches in a box in his pocket.

Five-hundred staff of the Tredegar-Markham-Oakdale companies enjoyed the ninth annual dinner at the Park Hotel, Cardiff in December 1913, where the chairman for the evening, Arthur Lawrence stated that Oakdale had hit 14,000 tons of coal a week and was now “able to fly by itself.”

Oakdale Colliery had to close temporarily in October 1914 due to so many of its miners enlisting in the forces. Yet by May 1916, it was the other way around and some men, and the company were desperate for them to stay. Tribunals had been set up to decide on appeals by men/masters who were called up but claimed that they were skilled workers and difficult to replace. Two such cases were in front of the Tredegar Tribunal on the 5th of May when an appeal was made on behalf of men who were deemed indispensable to Oakdale Colliery. The first case was of a man engaged in cutting chaff for 600 horses which they claimed was skilled work. The appeal was refused.

The next one concerned the surface time-keeper for 280 men. He was also the compensation clerk and dealt with the health insurance at the colliery and its 1,987 men. Since the war had started all the other clerical staff had left with the exception of this man. His defence claimed that he was almost as important as the manager. Four months exemption was granted.

It was added that since the war began 670 men from Oakdale Colliery had joined up. One of the first was the manager, Captain W. Clay Hepburn, although Hepburn was from a family of London solicitors he had married the daughter of David Hannah who was the general manager of the Ferndale and Tylorstown collieries and looked to mining for his career. When he was appointed manager of Oakdale Colliery, Hepburn also involved himself in the local community with one of those activities being a commission in the 1st Battalion of the Monmouthshire Regiment. In that capacity, he responded to the call for King and Country. Due to his technical capabilities, he was attached to the Royal Engineers and with them found combat with some of his men being taken prisoner. They were not forgotten by Mrs. Hepburn, who with some other women made weekly food parcels to be sent to them. Captain Hepburn was the manager until 1927. In June 1916 Hepburn was, amongst great ceremony, awarded a silver engraved sword by the men of Oakdale Colliery. It was stated that by then 10 men from Oakdale had been killed by the War. Two of the guest speakers at the ceremony had also lost sons, Alfred Onions, the treasurer of the SWMF and W. Stewart, colliery agent of Abertillery. Both had fallen on the 8th of May 1916 in the second battle of Ypres. The three Monmouthshire battalions suffered tremendous losses, at the beginning of that day the 3rd Battalions had 83 officers and 1,020 men, at the end of the day there were only four officers and 130 men left. It was in a similar vein in the trenches of the 1st battalion who started with 588 of all ranks and lost 439 of them either killed in action, wounded, missing or prisoner of war. The day became known as Monmouthshire’s Black Day.

The situation was so severe in October 1914 that it was decided to close the Brithdir pit and terminate the notices of the 250 men working there, plus close the Whitworth Pit in Tredegar with its 700 men and use them to fill the places in Bedwellty, Pochin, Markham and Oakdale.

Lt. Colonel A.T.A. Brown gave an interesting insight to Oakdale and Blackwood in his memoirs covering the 1913 period:

The first sod for the colliery was cut by Lord Aberconway (Chairman of the Company) in 1908 in a dale of oak trees overlooking the Sirhowy river, hence the name of Oakdale. The colliery was to be a steam coal pit with two shafts and a house coal pit. The offices were wooden huts situated near the shafts and not far away were the sinkers huts and workshop.

When I started in Oakdale in 1913 the sinking of the shafts had not been completed. The winding engine house, fan and boiler houses, powerhouse, coaling houses and the engineering and repairing shops were in process of building, and it was not until 1918 that the permanent colliery offices were built on the high ground overlooking the colliery. Some houses were also started on the estate which was later to provide a model village for the habitation of the colliery workers.

The nearest shopping centre to Oakdale at that time was Blackwood, which in 1913 was little more than a village, but with the advent of the colliery, the place developed rapidly. There were no ‘buses but there was a good train service from Newport to Tredegar. The local library was in a shop situated in the High Street and was administered by a number of older inhabitants of the town who had a strong social foresight. This foresight was to reach fruition in 1926 in the building of a magnificent library and social centre, under the auspices of the Miners Welfare Association, whose secretary, Alderman Sydney Jones, inspired its conception and completion…The Christmas of 1913 was our first in Blackwood and it was a good Christmas. Elsewhere in Britain, it was the best ever. Whiskey was just 4/3 (21p) a bottle, and poultry, pork, pies and cheeses were about a third of the 1939/45 pre-war prices…but in the old houses the miner had to bath in a tub in front of the fire with his wife replenishing to hot water from a boiler on the open fire. Indeed, between the two great wars the miners’ bathing was greatly improved by the introduction of the pit-head baths where a miner could dispose of the dirt and grime and get his pit clothes dried without carrying them into his home.

Oakdale Colliery was a subsidiary of the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company Limited whose Chairman was Lord Aberconway, and the Managing Director was Mr.A.S. Tallis. The Mining Agent was Major W. Clay Hepburn who also commanded the local Company of Royal Engineers (TA), while the manager was Mr, David Evans, a practical miner who had qualified as a Mining Engineer through the hard way of evening classes, practical experience at the coal face, and self-study by candlelight. He was an excellent manager, always keeping his eye on a good production, efficient ventilation and safety measures.

…I was also the Secretary of the Colliery Pithead Baths at Oakdale. The Oakdale Baths were the first to be built in the Sirhowy Valley and were opened by Mr. W.D. Woolley, the Managing Director of the Company, in 1936. The practical side of the baths was well looked after by Mr. Wm. Bennett, who also had an excellent well run canteen.”

The pit then encountered a problem of a different kind, the Coalfield was booming and they found it difficult to recruit enough men, which resulted in them paying the highest wages in the Coalfield in 1915. To attract men to the pit the average wage was around 10 shillings more than in neighbouring pits, and this was a significant sum considering the daily average wage was 7 shillings.

The manager in 1927 was D. Morgan.

On the 4th of April 1930 Sir Edward Johnson Ferguson, a director of the company, started a 75,000 kilowatt mixed pressure turbine that provided the power for Oakdale, Wyllie and Markham Collieries.

The start of the 1930s was no better for the colliery, and in 1931 this colliery was only working two to three days a week, but this didn’t stop a visit by Prince George to the colliery on December the 16th 1931. There were further problems in 1932 when the colliery was found to be ‘poaching’ coal belonging to the neighbouring Crumlin Navigation Colliery which resulted in 400 men being laid off.

Matters started to improve in 1933, but still, the TIC reported that they had laid off another 1,834 men throughout the company, with output 485,000 tons less than the previous year, they had still made a profit. In 1935 Oakdale employed 280 men working at the surface of the mine and 1,563 men working underground. It was then managed by G.G. Jones.

The Brithdir seam had been worked from its northern outcrop at Troedyrhiwgwair near Tredegar and right down to Oakdale. Due to the structure of the rock strata, the old workings acted as a water channel that brought millions of gallons down to Oakdale, which would, if not pumped away, flood the pit. To cope with this problem the old Llanover Colliery, approximately one mile to the north of Oakdale was purchased. Llanover Colliery was closed as a production unit in c1929. It was then bought by the Markham Steam Coal Company (a subsidiary of the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company) to serve as a pumping station to protect both Markham and Oakdale Collieries. The two original pumps were of the horizontal cylinder types and were operated by steam and were capable of pumping 60,000 and 120,000 gallons of water each hour respectively. They had great difficulty in dealing with the amount of water and frequently broke down. As a result of these breakdowns, the water rose approximately 80 feet up the shaft and the amount of water pumped at Oakdale increased. The company employed a diver to carry out pump repairs at the pit bottom.

Electric Sulzer type pumps were installed in February 1932; they were the largest deep well pumps of their type in the World and were capable of pumping 150,000 gallons per pump per hour. A specially constructed gantry was installed over the shaft to take their weight.

The late Jack Morris was a former pumpsman in the deep pits, he started work as a cleaner in the Waterloo winding engine house in 1925 when he was 14 years of age. He continued to work in various jobs at Oakdale Colliery until he retired, as a planned maintenance controller, forty-seven years and six months later. Here are some of his recollections:

The late Jack Morris was a former pumpsman in the deep pits, he started work as a cleaner in the Waterloo winding engine house in 1925 when he was 14 years of age. He continued to work in various jobs at Oakdale Colliery until he retired, as a planned maintenance controller, forty-seven years and six months later. Here are some of his recollections:

When I was 16 years old I had to move from being the Waterloo winder cleaner to another job. I went to work on the tip haulage. I worked days and afternoons (no one was allowed to work afternoons until he was 16 years of age). I was driving a 40 h.p. engine which took the muck out to the tip (muck from the washery and ashes from the boiler house). When I started to work there you could see all the houses in The Gray and the Collier’s Arms public house. When I had finished working there the tip had grown so high that you could not see any part of it. They then started to tip the muck the other side of the river towards the Rock and after many years when that was full they built the Ariel Rope Way and tipped towards Croespenmaen (that was some time in the 1940s).

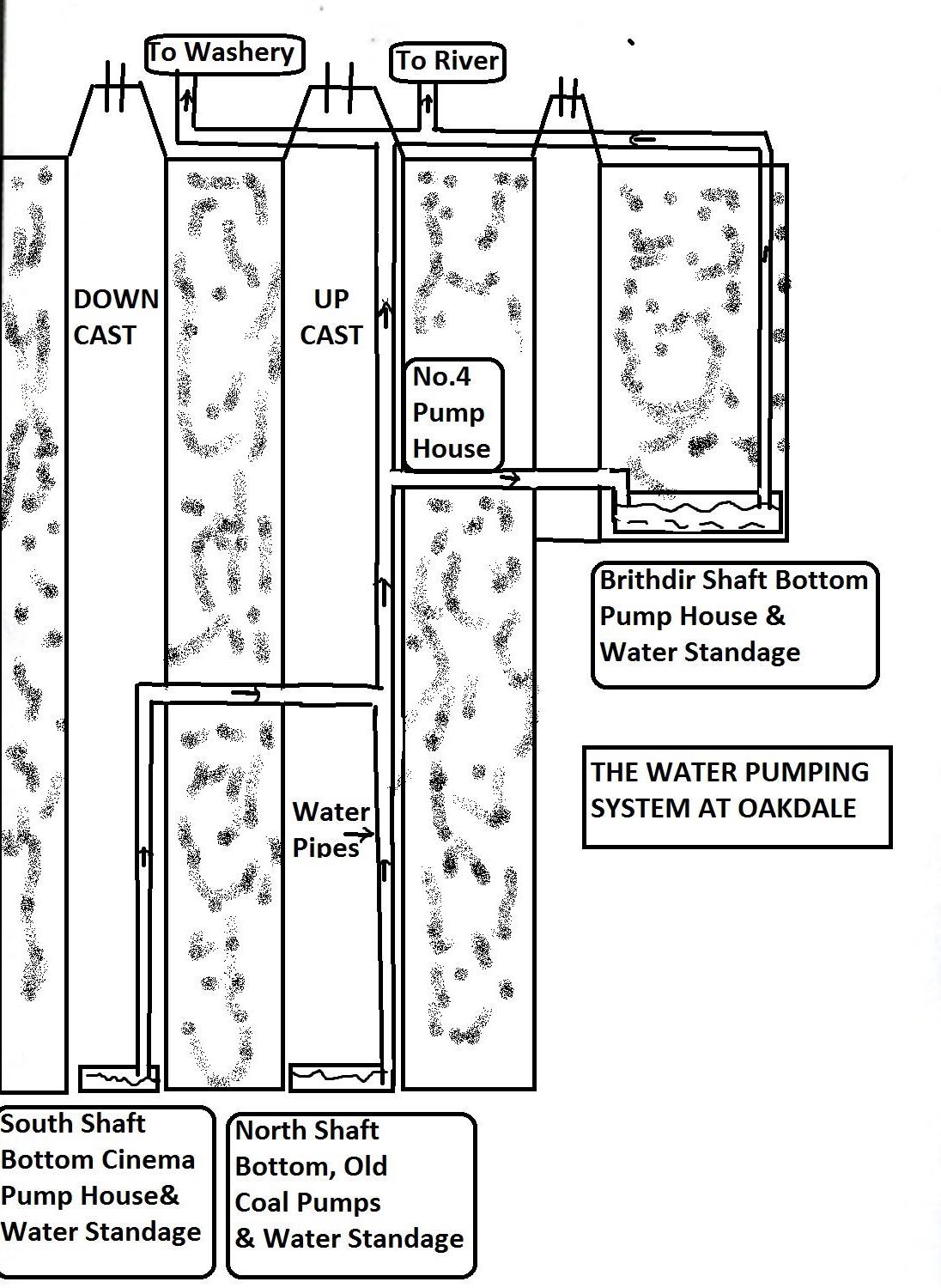

In about 1931 I went to work down the steam coal pit. I was given a job on the pumps and me and my mate used to work the day shift and night shift. There was a 250 h.p. pump near the bottom of the south shaft. All of the small pumps in the pit would pump to our pumphouse called the ‘Cinema Pumphouse’. There was a big water standage there. We would pump for 3.5 hours up to No.4 standage, No.4 pumphouse was halfway up the shaft between the north pit shaft and the south pit shaft. There was a standage there that would hold 3.5 hours of water from the Cinema Pump. I then went to No.4 pumphouse where there were two 250 h.p. pumps. I would get off the cage halfway up the shaft and stay there for about 3.5 hours to pump the water over to the Brithdir Pumphouse which was at the bottom of the Waterloo Colliery. They would then pump the water to the surface. In the Brithdir there were four 400 h.p. pumps. Some of the water was used at the washery to wash to coal and the rest of it was pumped into the Sirhowy River. Many years later there was a new pumphouse called the ‘Old Coal Pumphouse’. It was situated at the bottom of the north shaft.

There were two 400 h.p. pumps there and they pumped all the water to the Brithdir pumphouse doing away with the No.4 lodge room pumps that were halfway up the shaft. Later on, in about 1958, they put in two 600 h.p. pumps in the Old Coal Pumphouse and these pumps were big enough to pump the water in the south pit right up to the surface – and they are still doing this today. The Brithdir pumps only deal with the Waterloo pit water which is pumped to the surface. The Waterloo Colliery is 300 yards deep and the steam coal colliery is over 760 yards deep. I have tried to draw a map of the old system of pumping which existed in my time, and a map of the system which exists today.

I worked at the steam coal pit for about eight years and there were 86 horses in the pit at that time housed at the east stables, the west stables and the south stables. There was a gang of workmen called the hostlers who used to look after the stables and feed the horses. They worked a split shift starting work about 5 a.m. to feed the horses before they left for work on the morning shift at 7 a.m. The hostlers would finish at 8 a.m. after cleaning out the stables and then return to work at 1 p.m. to get the horses fed and ready for the afternoon shift. The horses were wonderful. Some of them went to agricultural shows where there was always a special class for pit ponies. They were fine horses and the ones in the steam coal pit were very big indeed. The ones in the Waterloo were much smaller because of the different heights of the roadways. The hauliers who drove the horses used to have the same horses every day and the horses got so used to the sound of their haulier’s voice that they understood every word spoken to them. The hauliers treated the horses like pets, and when the horses were up the pits during the strike some of the hauliers visited them every day. If a haulier was home ill, then someone else would have to drive his horse. Sometimes the horse would be ill-treated, and when the regular haulier started back to work and was told that his horse had had a rough time there would be a good row. I saw many a fight over this – no one was allowed to ill-treat a horse.

There were a lot of rats down the steam coal pit. They used to come down in the horses feed. All the chaff for the horse’s feed was cut and bagged at the granary which was at the bottom of Pen-Rhiw-Benji Hill. It was put into big bags and sent down the pit every day. There was a rat catcher in the steam coal pit and he went around putting down traps to catch them. The funny thing about it was that there was a lot of rats in the steam coal pit but not a single mouse. I never saw one. In the Waterloo Pit, there were a lot of mice but no one ever saw a mouse.

In 1934 the Oakdale Navigation Collieries Limited was based at 60, Fenchurch Street, London with the directors being; Lord Aberconway, Colonel Sir Edward Johnson-Ferguson, Evan Williams, N.J. McNeill and the general manager, W.D. Woolley. The company secretary was H.O. Monkley.

Pithead baths and a canteen were erected in 1936 for 1,728 men and extended in 1941 to accommodate 2,590 men. The men had to pay sixpence per week for the privilege with the baths costing £25,000 to construct and were opened by Mrs. W.D. Woolley, the wife of the managing director of the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company.

Around this time the electric generators at this colliery were providing power to Wyllie and Markham collieries. In 1939 this colliery was working the Meadow Vein, Old Coal, Big Vein, Yard and Rhas Las seams and employed 419 colliers and 386 colliers’ butties (assistants). The manager in 1938 and 1945 was still G.G. Jones.

In 1943 this colliery employed 1,542 men working underground in the Big, Meadow Vein and Upper Rhas Las seams and 334.

The TIC booklet of April 1946 states that Oakdale had twelve Babcock and Wilson double drum water tube boilers which were filled from overhead bunkers which were supplied by trucks from the washery.

A tunnel was provided for the ashes which fall direct into trams. The steam raised by those boilers operated the winding engines. Ventilation was by two Sirocco fans, each 154 inches in diameter, one was steam-driven and the other driven by electricity, they generated 600,000 cubic feet per minute of air. Other surface items included a granary to feed the horses at both Oakdale and Markham, shale crusher, stores, workshops and the lamp rooms, there were two lamprooms the main one was for handheld electric lamps and could hold 2,500, while the other held oil lamps and electric cap lamps. There were two screening plants, one for the steam coal pits, and the other for the Waterloo pit, there were four tipplers loading onto picking belts where the men would separate the rubbish from the coal. There were also two washerys, the No.1 and No.2, The No.1 could wash 125 tons of coal per hour and the No.2 could wash 140 tons per hour. Rubbish disposal was by an aerial ropeway of 120 tons per hour capacity and was 3,720 feet long with the main towers being 150 feet high and just introduced to the mine. It dumped its spoil to the northeast of the pits from a 200 ton capacity ferro-concrete bunker. No shunting locomotive was required for the sidings; it had been designed to be worked by gravity.

At that time the main problem with water was from the rocks above the Brithdir seam and four pumps, each of 80,000 gallons per hour capacity were installed. At the depth of 400 yards, more water had been encountered and another lodge room was built to house another pump of a capacity of 42,000 gallons per hour. Further to this there were further pumps in the Rhas Las seam (42,000 gallons per hour) and the Old Coal seam (two at 36,000 gallons per hour each).

Throughout the pit there were 3 x 300 hp haulages, 9 x 100 hp haulages, 25 x 40 hp haulages plus over 100 small compressed air haulages near the workings. The steam coal pits were working the Meadow Vein with a thickness of between 6 to 7 feet, the Rhas Las with a thickness of between 6 feet 6 inches to 8 feet and the Big Vein at a thickness of 3 feet. The Brithdir (Red Ash) seam was 2 feet 10 inches thick. The main roadways at that time amounted to 24 miles, despite extra supports enormous pressure squeezed in the Rhas Las roadways in an area where the Meadow Vein was being worked 50 yards underneath it.

The seams being worked were the Big Vein which was machine cut, the Meadow Vein which was both hand-cut in heading and stalls and machine cut and conveyor filled and the Upper Rhas Las which was worked on heading and stalls. New conveyor systems were installed and the NCB introduced the longwall coalface method of coal extraction into the pit. The manager at that time was J. Fox while in 1948 it was Phillip Weekes who went on to become Area Director. In 1952 the manager was A.E. Huxley.

In 1954/55 this colliery was one of 42 that caused concern to both the NUM and the NCB over the high level of accidents. In 1954 manpower had dropped slightly to 304 men on the surface and 1,525 men underground working the Big Vein, Meadow Vein and Yard seams. The manager was still J. Fox, with the colliery having its own coal preparation plant (washery), training centre and power station. In 1955 the NUM Lodge at this colliery was the largest in the Merthyr and Rhymney District and the second largest in the whole Coalfield with 1,920 members, 1,813 of them were working miners.

THE ANNUAL OUTPUT PER MAN AT N.C.B. PITS 1955 – 1958. 1961

Figures are in tons.

| Colliery | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1961 |

| Oakdale | 275.59 | 275.42 | 271.21 | 252.6 | 254.39 |

| Waterloo | 335.10 | 306.33 | 337.81 | 402.92 | 313.04 |

In 1962 the winding engines were converted from steam power to electricity. The order for the conversion of the south shaft was given to the Witton Engineering Works of G.E.C. with the specification that the electric winder should be capable of winding coal at a rate of 260 tons per hour and men at a rate of 1,200 per hour. The 27-foot diameter drum was retained and two identical driving systems were installed, one at each end of the drum shaft, the motors were1,250 hp. Both the electrical and mechanical parts were purchased from GEC’s Witton Works at a cost of £122,000.

The two d.c.driving motors were connected electrically in series and speed control was affected by variations of the Armature voltage. The DC supply for this was by four pumpless steel tank mercury arc rectifiers arranged to work on the figure “O” principal and fed from a twin unit 12 phase rectifier transformer energized from an 11kv three-phase 50Hz supply. The mercury arc rectifiers were connected in two groups of two in parallel. The DC voltage was controlled by transistorized grid drive units, and in addition, a current limit was applied to the system for both the drive and inversion conditions of the rectifiers.

A new Central Washery was completed in 1972.

In 1973 the M19 coalface was working the Meadow Vein at a gradient of one in four making it the steepest coalface in the South Wales Coalfield.

In July 1970 the colliery employed 1,251 men with 972 of them working underground. In the quarterly period between April and June 1974, the Big Vein seam produced 14,884 tons of coal, the Meadow Vein 41,862 tons, the Old Coal 82,173 tons, while development produced 2,368 tons, making a grand total of 141,287 tons for that quarter and 552,470 tons of coal for the 1974/75 year.

At that time there were six coalfaces available to be worked but only four were worked at a time, there were three in the Old Coal seam, one in the Big Vein and two in the Meadow Vein. There were 1,140 men employed at Oakdale, with 35% of them working at the coalfaces, 39% underground and the rest at the surface of the mine.

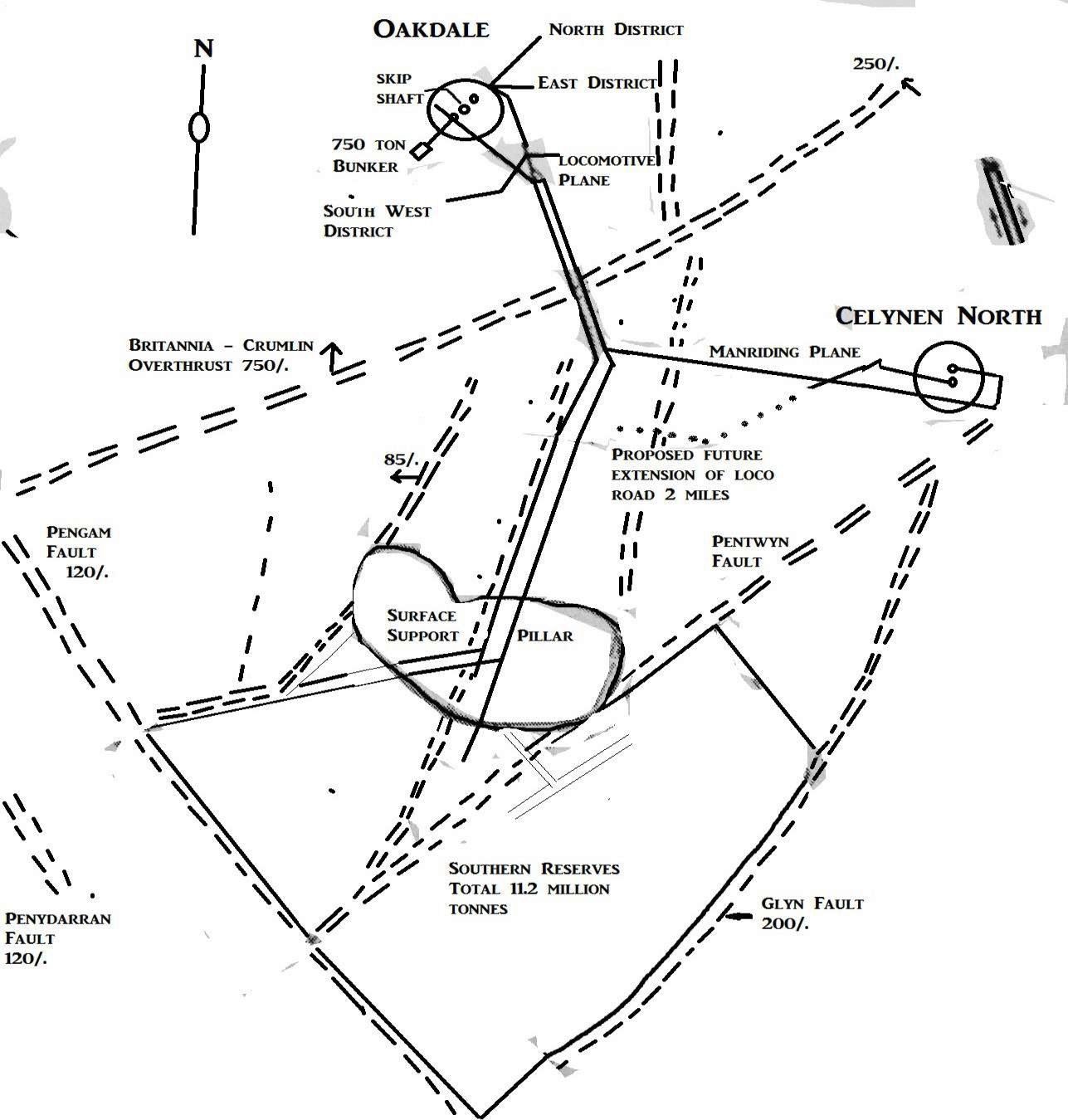

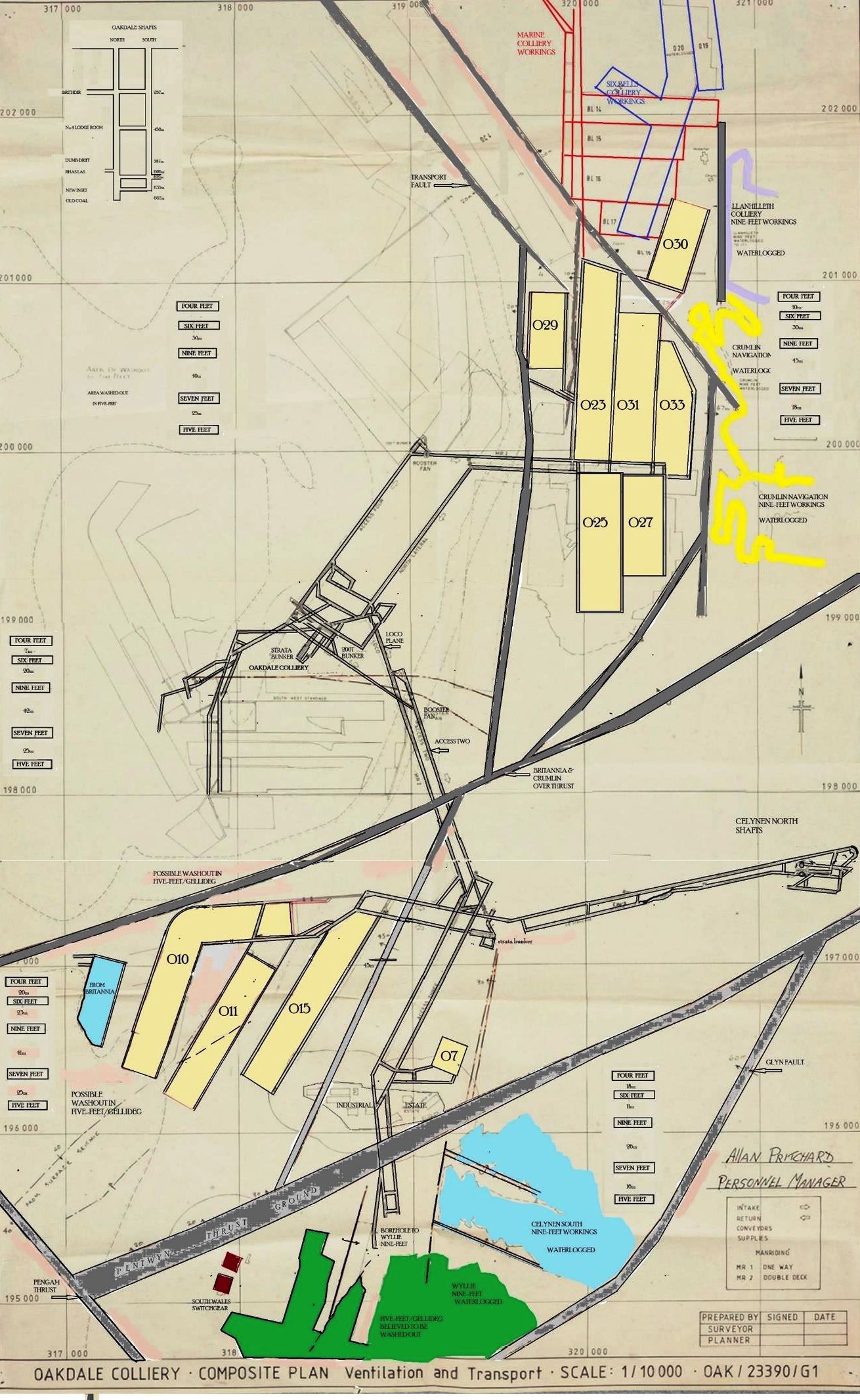

It was in the late 1970s the NCB invested an estimated £35,000,000 on a modernization scheme, which it was aimed to; increase efficiency by a reduction in non-productive jobs, the elimination of rail tolls, and the extension of manriding underground to increase the work time at the coalface. Also, it was intended to access 11.2 million tonnes of coal to the south of Oakdale. At that time the three pits combined had a total combined coal reserves of 11.4 million tonnes which would be exhausted in 10 to 13 years without major development. This, it was claimed, would give a life of twenty years at 900,000 tonnes of coal produced per year. The plan included driving 1,150 yards of roadways in one year linking Oakdale with Markham Colliery in 1979 and with the Celynen North Colliery in 1981, to make Oakdale the centre of this huge combine. The three pits all produced 301a prime coking coals and had combined manpower of 2,600. In 1978 the colliery consisted of four production coalfaces with the daily output being 1,800 tons of saleable coal with 1,167 men employed. Coal winding was from the 673-yard mark in the south shaft with supplies and man-riding from 665 yards deep in the north shaft from a newly constructed locomotive horizon. Skip winding was installed along with computerized monitoring of coal production and conveyance plus a complete renewal of underground and surface plant. Fourteen miles of high-speed 42-inch belt conveyors carried the coal production of seven coalfaces to the pit bottom where the 10.5-tonne skip brought the coal to the surface at a rate of 420 tonnes an hour (the old rate was 270 tonnes per hour) with it planned to raise 6,500 tons of coal a day at Oakdale, with a planned annual output of 887.000 tons of coal. A new inset was installed at a lower level in the north pit with a 750-tonne static bunker installed, the GEC battery locomotives were renovated after spending 25 years underground at Ogilvie Colliery. New 42 inch wide belt conveyors and Pikrose type endless rope haulages were installed to complement the three underground manriding/supplies systems with it estimated that the increased time that the men could spend at the coalface would give an extra 251 tonnes of saleable coal per day. On the surface of the mine, a new rapid loading and bunker system over British Rail track was installed with uprated power supply to the South Pit winder plus a new sales yard. A new tipping site had been established with a new rubbish conveyor to conveyor the dirt to the site.

A new tailings plant was installed plus a new tram circuit to the North Pit and new offices, material yard and road access. On top of this, the surface of Markham Colliery was demolished. In 1979 it was agreed to drive 2,900 metres of locomotive roadways and 1,600 metres of conveyor roadways into the old Wyllie Colliery reserves. Plus further roadways from the Celynen North workings. It was then estimated that the complex would have 22 million tonnes of reserves. There were 11.4 million tons in the current working area plus 11.2 million tons which was located two miles to the south in the old Wyllie take. Due to adverse geological conditions, the Wyllie reserves were never reached. In 1983 this colliery was losing £7.50 on each tonne of coal it produced.

The colliery made a remarkable recovery after the 1984/85 miner’s strike and obtained 120% of expected output within a month of starting back with an output per man shift of just under two tonnes. The NCB reporting: “Oakdale/Celynen North: The recovery had been very satisfactory with more than 120% of normal recovery having been achieved despite problems with the skips.”

Yet the effects of the strike were not over, on the 17th of May 1985, ninety-two men walked out on strike, along with 670 men at Taff Merthyr Colliery in protest over the life sentences passed on R.D. Hancock and R. Shankland who were involved in the unfortunate incident which ended up with the death of a taxi driver. John Haigahway who worked at Oakdale was quoted as saying; “It was not premeditated at all. It was just a silly action that should never have happened.”

A new manager was installed, Desmond Caddy, who in his own words; “I admired the way she handled the strike.” He was referring to Margaret Thatcher.

The signs that the end was near became evident in March 1989 when it was agreed to reduce the surface manpower by forty, with 10 jobs at the tipping site, 12 on pumping and 18 on the surface of the mine, 25% of the surface total to go. Even though Oakdale was the most profitable pit in South Wales the previous year.

In July 1989 Oakdale was placed in the review procedure. British Coal claimed that it was losing £130,000 per week, even then the NUM Lodge Secretary, Colin Tapper, had hopes that it would stay open. Due to geological problems, the pit was down to one coalface in operation, and in the first fourteen weeks of 1989, it was producing 12,500 tons a week when 16,500 tons was the target. BC coal stated; “because of a worsening geology and production results a joint investigation of the pit situation should be made immediately after the holiday.”

Oakdale Navigation Colliery was the last deep mine to work in the County of Gwent, closing in August 1989. Demolishing was completed by the 30th March 1990.

The Oakdale Colliery site was reclaimed in 1995 to form 4 large plateaux comprising of 170 acres for industrial development. The reclamation project itself was designed in such a way that the site also consisted of large areas of semi-natural vegetation such as woodlands, ponds and areas of unimproved and marshy grassland. An extended Phase 1 ecological survey was undertaken by the WDA in 2000.

The site was also extensively landscaped /planted with native trees to form large woodland blocks on the batters around each of the plateaux. In the last 3 years, additional gateway landscaping was added to the site main access point on the Pen Y Fan Industrial Estate. The site is zoned for B1, B2 and B8 development.

Some Statistics:

- 1907: Manpower: 235.

- 1908: Manpower: 328.

- 1909: Manpower: 235.

- 1910: Manpower: 295.

- 1911: Manpower: 327.

- 1913: Manpower: 711.

- 1915: Manpower: 2,127.

- 1916: Manpower: 2,200.

- 1918: Manpower: 2,202.

- 1919: Manpower: 1,635.

- 1920: Manpower: 2,622 with Waterloo.

- 1923: Manpower: 2,549.

- 1924: Manpower: 3,312 with Waterloo.

- 1925: Manpower: 3,285 with Waterloo.

- 1926: Manpower: 3,161 with Waterloo.

- 1927: Manpower: 3,134 with Waterloo.

- 1928: Manpower: 3,465 with Waterloo.

- 1929: Manpower: 2,805.

- 1930: Manpower: 2,231. Output: 900,000 tons.

- 1931: Manpower: 2,830.

- 1932: Manpower: 2,050.

- 1933: Manpower: 1,527. Output: 900,000 tons.

- 1934: Manpower: 1,477. Output: 600,000 tons.

- 1935: Manpower: 1,843. Output: 600,000 tons.

- 1937: Manpower: 1,886.

- 1938: Manpower: 2,115.

- 1939: Manpower: 2,075. Output: 700,000 tons.

- 1941: Manpower: 2,315. Output: 700,000 tons.

- 1942: Manpower: 2,075.

- 1944: Manpower: 2,075.

- 1945: Manpower: 1,876.

- 1947: Manpower: 2,092. Output: 357,800 tons.

- 1948: Manpower: 1,623. Output: 394,300 tons.

- 1949: Manpower: 1,882. Output: 441,500 tons.

- 1950: Manpower: 1,882. Output: 476,200 tons.

- 1951: Manpower: 1,844. Output: 490,400 tons.

- 1952: Manpower: 1,844. Output: 486,600 tons.

- 1953: Manpower: 1,779. Output: 487,100 tons.

- 1954: Manpower: 1,779. Output: 515,700 tons.

- 1955: Manpower: 1,801. Output: 496,334 tons.

- 1956: Manpower: 1,856. Output: 511,178 tons.

- 1957: Manpower: 1,951. Output: 599,138 tons.

- 1958: Manpower: 1,847. Output: 466,650 tons.

- 1960: Manpower: 1,900. Output: 477,000 tons.

- 1961: Manpower: 1,889. Output: 400,550 tons.

- 1962: Manpower: 1,902.

- 1964: Manpower: 1,783.

- 1969: Manpower: 1,221.

- 1970: Manpower: 1,334.

- 1971: Manpower: 1,218.

- 1972: Manpower: 1,191.

- 1974: Manpower: 1,150. Output: 210,000 tons.

- 1975: Manpower: 1,109.

- 1979: Manpower: 945. Output: 226,000 tons.

- 1980: Manpower: 971. Output: 226,395 tons.

- 1981: Manpower: 926.

- 1982: Manpower: 873.

- 1984: Manpower: 867.

- 1986: Manpower: 1,400.

- 1989: Manpower: 873.

This information has been provided by Ray Lawrence, from books he has written, which contain much more information, including many photographs, maps and plans. Please contact him at welshminingbooks@gmail.com for availability.

Return to previous page