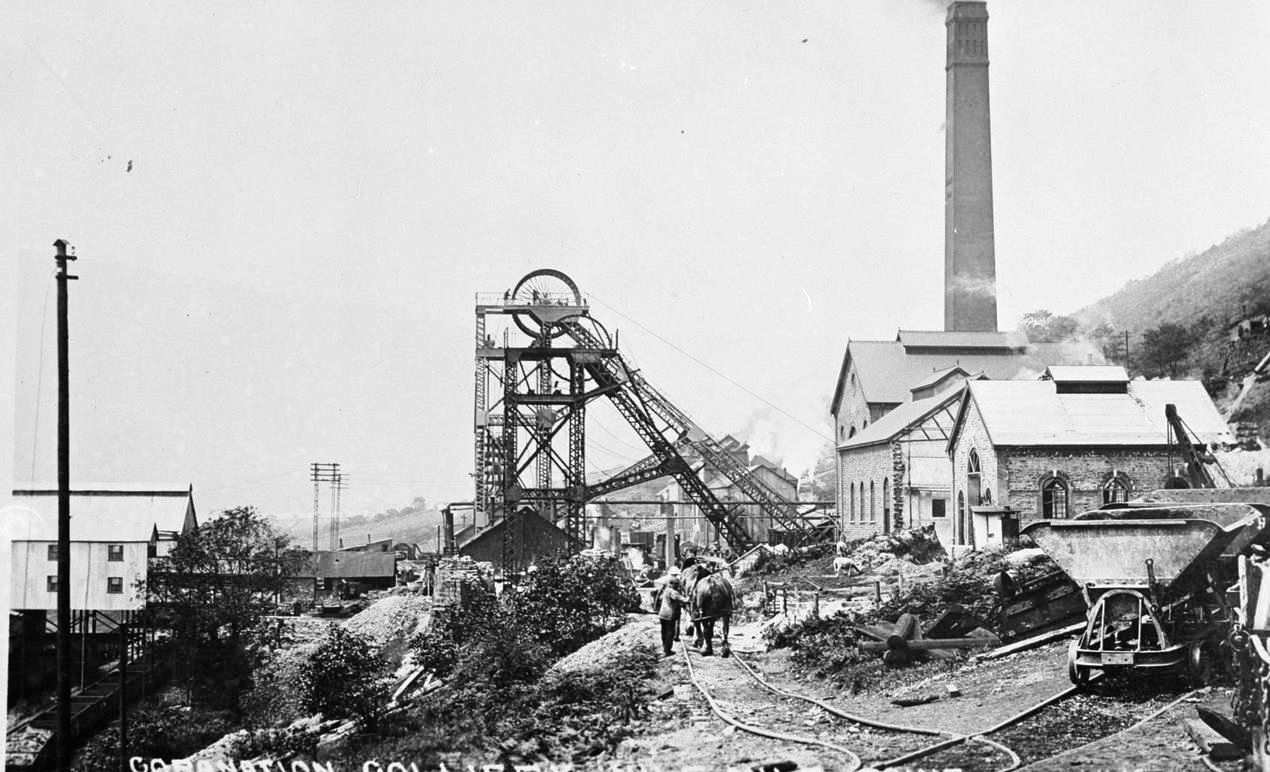

Coronation Colliery

Cwmfelin-fach (ST 1927 9131)

The sinking of the three shafts of this colliery was commenced in July 1902 by the owners Burnyeat and Brown and Company. In 1903 they raised the cash by offering Preference and Debenture shares to a value of £60,000 each to the general public. It proved to be a good investment as profits for the company rose from £26,008 in 1904, to £103,538 in 1908 with a dividend of 15% plus a bonus of 100% paid on ordinary shares in 1909. In the peak year of 1913, the profit for the company was £146,854. In 1908 the manager was Thomas Falcon and in 1918 it was D.R. Morgan.

The East and West Pits were sunk to the steam coal seams of the Lower and Middle Coal Measures at a depth of 394 yards. The Rock Vein Pit was sunk to the Rock Vein (No.2 Rhondda) seam of the Upper Coal Measures for house coal. This pit was 200 yards deep.

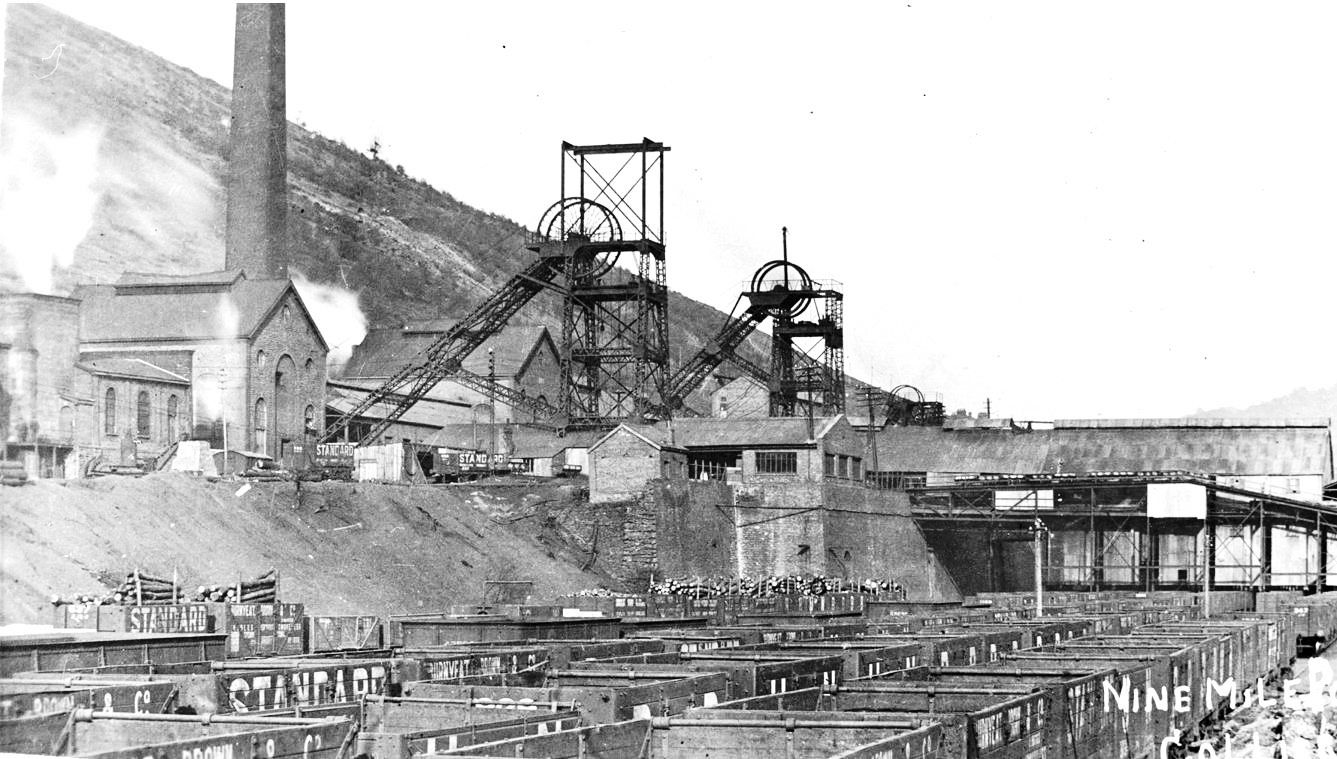

This colliery was originally called Coronation Colliery but was renamed to Nine Mile Point, which was its distance from Newport Docks; it was also called, for sales purposes, Sirhowy Black Vein Colliery.

The surface plant was arranged to deal with 3,000 to 4,000 tons of coal a day from the three pits, which all had double-decked carriages with both decks being loaded/unloaded simultaneously onto a double landing.

In 1913 this colliery was in full production and employed 2,105 men and was managed by R.J. Strong. Between 1904 and 1915 this company made profits totalling £760,928 and in 1915 its board consisted of; F.S. Watts, Chairman, S.K. George, Colonel A.K. Wyllie, H.S. Sanders Clark and John Arthur Jones (South Wales Coal & Iron Companies by the Business Statistics Company).

The workmen at this colliery were probably the most militant in the whole of the South Wales Coalfield, the owners in 1920 citing; 24 strikes in 1919, 9 in 1918, and 16 in 1917. The strike of early 1920 was over two men not being paid the minimum wage to which the union claimed that they were entitled. The union then demanded that the overman involved be dismissed. The owners accused the men of breach of contract by walking out without notice. Up to the 20th of April, the men had been out for a month and had lost £40,000 in wages in total and 50,000 tons of coal had been lost. 150,000 men throughout the Coalfield then issued notices in support of the men at the ‘Point raising fears of a wholesale strike. Interestingly Risca Colliery refused to support them, only eight men out of 2,000 voting to strike. On the First of May, a special conference of the South Wales miners voted by a majority of 71, out of over 4,000 votes not to support a strike and to urge the ‘Point men to go back to work. The men went back to work but the industrial relations problems and strikes continued.

In 1922 the Nine Mile Point owners attitudes hardened, notices to terminate their contracts were given to 80 miners who wouldn’t accept the price list offered to them by the company, and then the lamps of a further 70 men were stopped when they turned up for work on a Monday morning. Coupled with these actual happenings, rumours abounded that the new owners intended to stop all of the old customs and even shut the pit permanently. The anxieties and tensions amongst the men gathered for work that morning suddenly exploded into collective action. Up they went as a body to the manager’s office, smashing the windows and entering the building and dragging the manager out, amid various threats from the workmen he was dragged up the hill to the workmen’s hall, and despite the presence of a police superintendent and six bobbies he signed an agreement that “all previous customs at this colliery to prevail in future. Sixteen of the miners were arrested and charged with riotous assembly, assault and intimidation. At their trial, seven were discharged, three of them got six months hard labour and two were bound over for 12 months.

An uneasy peace hung over Cwmfelinfach and Ynysddu, but this wasn’t to last very long, and in March 1923 trouble again erupted, this time over the thorny problem of non-union labour. Obviously, the men at the Point wanted a union that would defend them against the worst excesses of the company policy, and just as obvious the company wanted to maximise profits and looked upon organised labour as an impediment to this. The answer seemed to be in the formation of another union, believed to have been sponsored by the Ocean Company and certainly encouraged by them. Anyhow, the good old boys at the Point weren’t having any of this, and a few hundred of them trotted up to the home of one of the leaders of the new union and humbly asked him to join the Fed, he graciously declined and all hell broke loose, and well as his windows and roof slates. Off they went to the treasurer of this, as they saw it, scab union’s house and repeated the trick. The result of all this was that six men got four months jail, and one got six months, all with hard labour.

An uneasy peace hung over Cwmfelinfach and Ynysddu, but this wasn’t to last very long, and in March 1923 trouble again erupted, this time over the thorny problem of non-union labour. Obviously, the men at the Point wanted a union that would defend them against the worst excesses of the company policy, and just as obvious the company wanted to maximise profits and looked upon organised labour as an impediment to this. The answer seemed to be in the formation of another union, believed to have been sponsored by the Ocean Company and certainly encouraged by them. Anyhow, the good old boys at the Point weren’t having any of this, and a few hundred of them trotted up to the home of one of the leaders of the new union and humbly asked him to join the Fed, he graciously declined and all hell broke loose, and well as his windows and roof slates. Off they went to the treasurer of this, as they saw it, scab union’s house and repeated the trick. The result of all this was that six men got four months jail, and one got six months, all with hard labour.

In October 1923 the Company announced that it intended to close the mine and that work would be suspended at the end of the month. They this time stated that before the war weekly output was 16,000 tons but then it was only 10,000 tons due to the men working on a ‘go-slow’.

In October 1923, in order to get their way, the company threatened to shut the pit posting this notice;

The director’s regret, owing to the serious loss sustained by the Company, due to the prohibitive cost of working, they find it impossible to continue carrying on the colliery and they have no alternative but, to close down at the end of the current month.

This was a ploy to get the men to accept a wage cut, and within the current economic situation within the South Wales Coalfield, there was no alternative than to do so or suffer life on the dole. Following consultations with the South Wales Miners’ Federation, the notices were withdrawn.

The general strike and lockout in 1926 was due again to the coal owners demands for concessions from the miners. The miners refused to accept the owner’s terms, and on the 30th of April 1926 the lock-out notices expired and the pits stopped. On November 23/24th, the South Wales Executive Committee met the Owners but failed to agree on terms. On November 29th a ballot of the south Wales miners voted in favour of a settlement, and on the 1st December 1926, the miners returned to work on the Owners terms. Defeated.

The colliery was again closed in November 1928 when the men refused to accept reduced wages, which the owners claimed were necessary due to a lack of trade.

Manpower had dropped to 1,600 men by 1934, although in 1935 manpower had increased to 312 men on the surface and 1,628 men underground working the Black Vein (Nine-Feet), Big Vein (Four-Feet), Lower Black Vein (Five Feet/Gellideg) and Rock Vein (No.2 Rhondda) and Five-Feet seams. During this period a major customer was the local chemical works which claimed to make 137 different commodities from coal.

In July 1940 the newspapers reported:

Mr. D. J. Treasure (coroner) conducted the inquest and recorded verdict of “natural causes.— The discovery of Winmill’s body lying on a tram track at Nine Mile Point Colliery. Ynyaddu, where he was employed as a watchman, was described by Thomas Smith. banksmau, of ” I came out of the stoke-hole and saw a black shadow lying between the rails.” said Smith. I found it was the body of Mr. Winmill. His arms were folded under him and his nose was bleeding.’ Replying to the Coroner, Smith said lie could see no obstruction over which Winmill could have fallen unless it was one of the rails. In reply to Mr. Norman Moses (Messrs. T . S. Edwards and Son, Newport), who represented the family of Smith said that Winmill had a torch but it was out. An engine driver, said he met Wimnill. who gave him some instructions. He appeared to be quite normal and had his dog with him. He was walking away when the witness saw him last. Afterwards. he heard of the tragedy. Evidence of identification was given by Orlando Winmill Son, who said his father was brought home dead at 3 am. on Tuesday. 25th. G Rocyn-Jones. Monmouthshire pathologist. said the cause of death was heart failure following fatty degeneration of the heart due to sithcroina of the coronary arteries. There were some marks on the face. These were superficial and were consistent with having been caused by contact with the ground. There was no fracture of the skull and no haemorrhage inside the brain or skull. One of the coronary arteries Mocked by calcification. Recording a verdict of “natural causes,” the Coroner said it was impossible to say whether Winwill had a heart attack and fell, or whether he ‘tripped and then had the heart attack.

On the 11th of November 1940 Clifford Vines was aged only 17 years and lived at Coronation-terrace. Pontymister, when he was killed by a fall roof.

On the 18th of May 1945, the first stay down strike since 1941 brought this pit to a stop for 36 hours. Eventually, management agreed to remove the official at the centre of the strike. This article from May 1946 shows the caring side of the industry. The Happy Miners of Talygarn by Our Own Reporter:

There could be no better title for this story than “The happy miners of Talygarn.” For happiness is the keynote of all activity at the South Wales Miners’ Rehabilitation Centre at Talygarn, near Cardiff. Every member of the staff, from Matron Irwin and Assistant Matron Thomas downwards, strives for it.’ The welfare of the injured miners always comes first as I saw for myself on Wednesday. With Alderman W. J. Sadler. general secretary to the South Wales Miners’ Executive, and Mr. D. D. Evans, assistant secretary. I spent the day watching the men being ” rehabilitated ” and saw how thoroughly an expert staff goes about its job. At the moment the centre is full and there is a waiting list – and no wonder, for, as one of the patients told me. ” This is a real home from home.” “Captain” S. S. Parry, of Nine Mile Point. is typical of the 70 miners in the centre. They call him captain because he has been there longest ” I have been here nine months,” he said to me. “I was injured by a roof fall at the Nine Mile Point Colliery and sustained a dislocated shoulder and complications. We have every care and attention and most of the men are sorry when the time comes for them to leave.’

On Nationalisation in 1947 Nine Mile Point Colliery was placed in the National Coal Board’s, South Western Division’s, No.6 (Monmouthshire) Area, and at that time employed 234 men on the surface and 1,027 men underground working the Five-Feet, Lower Black Vein, Black Vein, Big Vein and Rock Vein seams. The manager was O. Powell. This colliery had its own coal preparation plant (washery).

It wasn’t all strikes and lay-offs, it was the opposite with some who get enough of the place:

50 YEARS IN MINE, HE STILL WORKS 7 DAYS EVERY WEEK

After fifty years’ work underground, Jim Davies, 69, Welsh miner, still puts in seven days a week—producing, as he says, coal and food. Jim, whose home is at Pentwynmawr, near Blackwood (Mon), has been employed at the Nine Mile Point Colliery near Blackwood, for the past forty years and is still at work there. He cycles eight miles to and from his Work. When he gets home he starts work on his three-acre smallholding, cultivating vegetables, looking after his cattle, ponies and poultry. On Sundays, he works eighteen hours on the land. “I am a farmer’s son, but I went to the mines fifty years ago, and I have never regretted it,” he told the Daily Mirror yesterday. “The country needs coal and food. I try to produce both, and many more could do likewise,” said Jim.

Poor Ivor Lloyd didn’t enjoy much time enjoying Nationalisation, the ripper was descending the shaft at the beginning of his shift when he collapsed and fell out of the carriage 400 feet to his death on the 3rd of April 1948. In December 1949 – A verdict in accordance with medical evidence, “Death, from haemorrhage of the brain,” was, recorded at the Blackwood inquest, yesterday on William Richard Ruscoe, aged 46, Graig View, Ynysddu, a coalman employed on the surface at Nine Mile Point Colliery, who died while at work.

It was in August 1950 that perhaps the strangest death occurred at the colliery, Thomas Moore was 67 years old and had retired from Nine Mile Point. On his way to the pit, he shouted ‘cheerio Fred’ to his friend Fred Oram he then climbed of the safety gate and fell down the shaft. A note was found near the pit top saying that you may go to my home 83 Islwyn Road Wattsville, and you will find my wife dead. Later on police did find Mrs. Moore lying dead with severe head injuries.

The Rock Vein Pit was closed in 1954. But major investment came to the ‘Point in 1957 when the old steam winders were electrified. Electrical equipment for the winders was made by Metropolitan-Vickers. Mechanical parts by Robey and Co., Ltd., and M. B. Wild and Co.. Ltd On the 2nd of February 1959, Percy Bendle, a pit deputy at the ‘Point who lived at Abercarn received the Daily Herald’s Order of Industrial Heroism which had been dubbed the workers V.C. He had bravely rescued a workman trapped under a roof fall with no regard for his own safety.

The attitude of the men had also mellowed somewhat with them offering to work a voluntary Saturday shift to help ease the Nation’s shortage of coal. It was a terrifying two hours for 22 miners on the 25th of M<ay 1959 when they were stuck in the middle of the shaft when a guide rope twisted. There was a severe drought throughout the country in June 1960 and the pit needed water to continue surface operations. Officials decided to tap into a council water hydrant without informing the council with the result that the top half of Wattsville was without water until the council tracked down the ‘fault’.

On the 11th of October 1963, the deputy for the M11 District reported an unusual smell, the following day a ‘haze came from the waste indicating that heating had occurred there. Work was immediately halted and it was agreed to try and put the fire out by entering the waste. Fire-fighting gear, canaries, smoke helmets and revival apparatus was placed on hand but after travelling 30 yards it was deemed too dangerous to travel any further and the district was sealed off on the 15th of October 1963. There was more bad luck in store for the colliery when on the night of the 12/13th of November 1963 excessive weight pushed down the roof in the M18 district of the Lower Black Vein seam, this released an inrush of water through the roof and the whole coalface was flooded. The water had come from old workings ten yards above the current ones. By the March of 1964 output per man shift had dropped down from 23 cwts to 7 cwts, 35 men were transferred to Risca Colliery and the OMS rose to 16 cwts. Losses were then running at £1.25 per ton of coal produced or £14,000.

The NCB then informed the men that they wanted 150 men to transfer immediately from the West Pit to Penallta followed by the closure of the East Pit by the end of 1964. The NUM Lodge at the colliery decided to fight the closure and was initially backed by the NUM Area Executive Council, but at the meeting on the 28thof April 1964, the AEC accepted closure. The Lodge demanded an Area Conference of all the South Wales Lodges but this only endorsed the AEC decision.

On the 13th of May 1964, a conference of the South Wales NUM voted against their own executive and refused to accept the closure of the ‘Point. The executive then agreed to take the fight to the National Union. Nevertheless, Nine Mile Point Colliery closed on 25th July 1964.

This information has been provided by Ray Lawrence, from books he has written, which contain much more information, including many photographs, maps and plans. Please contact him at welshminingbooks@gmail.com for availability.

Return to previous page