Mountain Ash, Cynon Valley (ST 0506 9890)

Mountain Ash, Cynon Valley (ST 0506 9890)

One coal speculator who can lay claim to introducing south Wales coal to the wider world is John Nixon, in an article in the Merthyr Guardian dated 12th May 1860, John Nixon related the part he had played in making the Cynon Valley the most important coal mining area in Great Britain:

I believe that l am right when I say that we have here from 4,000 to 5,000 acres of coal to be worked. I look to Mountain Ash surviving Aberdare in prosperity. I will tell you the cause of my coming down here in the year 1840, 1 went to London from the North of England, and I happened to go onboard one of those boats now called penny boats. I saw the stoker throw continuously coal into the furnace, and when I looked at the funnel I saw no smoke. This was a wonder to me as in the North of England I had been used to seeing smoke. I asked him to allow me to look at the coal and said “I will give you a shilling, and if you will let me feed the fire I will give you another” I threw some coal on the fire – but there was no smoke I then asked him where he got the coal, and he replied from Meartheere in Wales. He could not say Merthyr. I at once made It my business to come down here. At this time there was no railway to Aberdare, and the coal had to be conveyed down by the canal.

I went to Mr. Powell and told him that if he wanted a market for his coal at Duffryn, I was willing to….introduce his coal into France….The year 1840 was a great epoch in this district, as that was the year when the first cargo of coal was taken to Nantes, and given away to the customer That same year we entered into a contract to supply them with 3,000 tons.

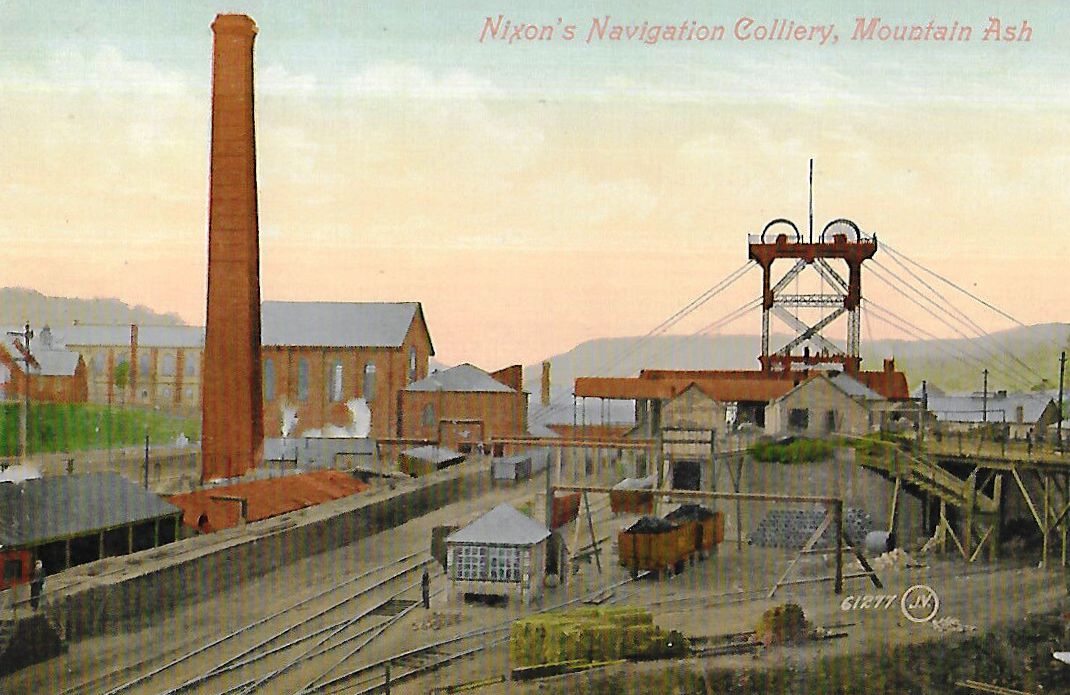

John Nixon’s relationship with Thomas Powell was certainly not a bed of roses though, Powell soon refused to pay Nixon’s commission on the sales and the matter resulted in a Court Case. However, Nixon made enough money out of selling coal to enable him to sink his own pits, and he leased the mineral rights in the Mountain Ash area from the Marquis of Bute and sunk the Werfa pit. He then took an enormous gamble and sunk the Navigation Colliery, a venture that nearly ruined him the sinking took seven years to reach the Four-Feet seam and cost £113,772. The colliery was in production by 1860. John Nixon retired in 1894 and died in 1899. A line in the Bristol Mercury of the 31st of July 1899 read:

The late Mr. John Nixon, of Nixon’s Navigation Colliery Company, Limited, left estate valued at £1,155,069 17s 6d.

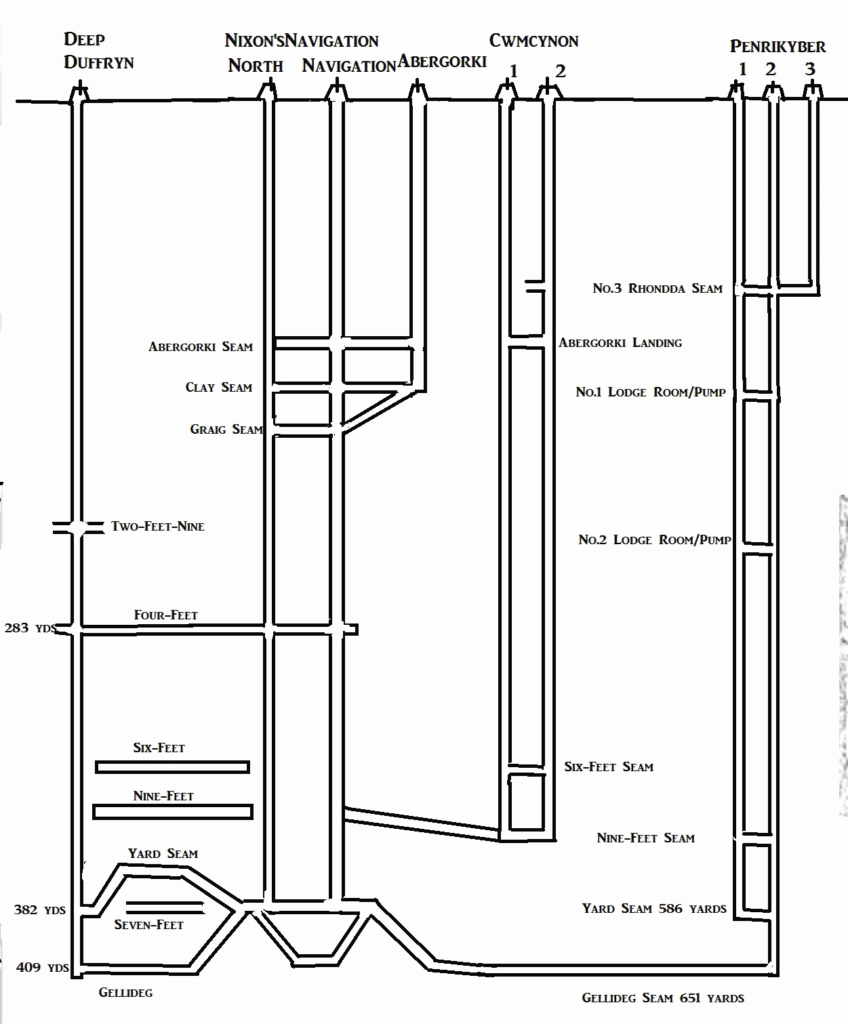

He was replaced as head of Nixon’s Navigation Company Limited by H.E. Gray. The South Pit was eighteen feet in diameter and originally sunk to the Four-Feet seam at a depth of 1,095 feet, it was later deepened to 1,350 feet 5 inches. This was just below the Seven-Feet seam level. The South Pit had two winding engines and was divided in half to allow it to wind from the Four-Feet and Nine-Feet landings at the same time. The winding engines had two 33 inch cylinders with a six feet stroke, both engines had spiral drums ranging from 10 feet up to 20 feet. The winding rope was made of steel and 1.5 inches in diameter. The cages were double-decked and a wind could be completed in 75 seconds. The shaft was 18 feet in diameter. The North Pit was the upcast ventilation shaft and was sunk to the same seam but to a depth of 1,333 feet 2 inches.

The pits were 130 yards apart. Two Waddle fans were later (1880) used for ventilation, one was 42 feet in diameter and the other 40 feet in diameter. While in 1889 another 18 feet in diameter Waddle fan was installed. In this part of the Cynon Valley there were twelve seams between the Gellideg and Two-Feet-Nine seams in about 375 feet of the vertical ground. These seams totalled a thickness of 46.5 feet, with an average thickness of 3 feet 10 inches per seam. Based on the Nine-Feet seam these coals were classed as type 201B Dry Steam Coal, low volatile, usually non-caking, and used for steam raising in the boilers of ships, locomotives etc.

Nixons North Pit, sunk by John Nixon, the founder of Nixon’s Navigation Coal Company (see above), with its history being the same as the Navigation Colliery. The winding level at this pit was from the Seven-Feet seam level at a depth of 440 yards. The shaft diameter was 17 feet. The fan pit at this colliery was used as a standby for the Deep Duffryn Colliery until the 1970s.

There was a particularly bitter strike in 1893, which very often erupted into frustrated violence. This is how the Western Mail, on August the 21st, viewed an incident in Mountain Ash:

The first outbreak of hostilities at Mountain Ash took place on Friday night when the police were stoned by the strikers. At this centre are situated the principal collieries of Nixon’s Navigation Coal Company and the Powell Duffryn Company, which employ many thousand men. The pits at Mountain Ash are Nixon’s Deep Duffryn, Nixon’s Navigation, Nixon’s level, the Lower Duffryn Pit, and the George Pit, the latter two being situated halfway between Mountain Ash and Aberaman. In order to more effectually ensure peace and quietness in the district seven or eight constables in charge of a sergeant, had been drafted from Swansea, and half a dozen men with Inspector Rutter at their head were imported from Penarth and accommodated at the New Inn. Amongst the strikers were heard many expressions of dissatisfaction at this augmentation of the local police force, especially when some of the men were told that the expense would have to be borne by the count and not by the coalowners. The strikers lounged about the streets all day, but nothing of interest occurred until dusk on Friday evening. At Nixon’s Navigation Colliery in the centre of the town is a crossing over the railway and a footbridge known as Nixon’s Crossing. This leads to a road through the colliery premises, which is used by the general public and acknowledged as a right of way.

On Friday evening the colliery officials, for the better protection of the company’s property, gave instructions that this crossing was to be stopped, and a number of policemen at once took up their position and prevented anyone from passing through the colliery yard. When this became known hundreds of the strikers soon assembled at the spot, and as ill-luck would have it, exactly opposite the crossing was a heap containing many tons of stones to be used for street repairs. Such a temptation could not be resisted by the crowd, and as darkness set in, volleys of stones were directed at the police, and with such effect that assistance had to be sent for.

At one time matters looked serious, and it was feared that an attack might be made on the colliery. The police, however, drew their batons, and quickly cleared the vicinity of the crossing, but not before several of their numbers were severely bruised by stones…On Saturday the horses, numbering about 140 were brought up from Messrs. Nixon’s pits and turned into the fields. The extra police have been posted to the various collieries in the locality.

The men at Nixon’s Navigation were the first to break the strike in this area and returned to work on August the 25th. On the Thursday April the 12th 1894, a family scuffle reached the newspapers when Edward Picton was convicted of violent assault on his brother, John Picton while working in the Six-Feet seam at this pit. He was fined 40 shillings or a month in prison. The manager in 1878 was W. Bevan and in 1893/6 it was James Davies who employed 1,187 men underground and 371 men on the surface of this mine in 1896. In 1908 William Morgan was the manager and it employed 1,189 men underground and 646 men on the surface. All the men working at this colliery (1,200 in total) were given notices in May 1909 and the pits were sunk to the lower seams.

In 1913 the colliery was managed by W. Morgan and employed 1,386 men. This Company was a member of the Monmouthshire and SouthWales Coal Owners Association. In 1916/19/23 the manager was J. Jones with the colliery employing 1,898 men in 1916, 1,832 men in 1919 and 1,383 men working underground and 631 men working at the surface of the mine. In 1929 Sir David Rees Llewellyn took control of the company and renamed it Llewellyn (Nixon) Limited and by 1930 it employed 575 men working underground. In 1935 it employed 65 men on the surface and 850 men underground and produced 300,000 tons of steam coal. The manager during that time was Thomas Jones. In 1938 Mr. Jones was still manager and this pit employed 221 men underground and 222 men on the surface. In 1934 Llewellyn (Nixon) Limited was based at the Navigation Offices, Mountain Ash with the directors being; Sir David R. Llewellyn, W.M. Llewellyn, H.H. Merrett, Sir John F. Beale, T.J. Callaghan and J.H. Jolly. It controlled six collieries that employed 6,280 miners who produced 2,100,000 tons of coal in that year.

The colliery closed as a production unit in 1941 but was retained for pumping and ventilation purposes for Deep Duffryn Colliery and for surface workshop facilities. In 1945 there were only 8 men working underground and 226 men working on the surface of the mine. Mr. Jones was still the manager. On Nationalisation of the Nation’s coal mines in 1947 this colliery was used as a maintenance depot by the National Coal Board.

Some of those who died at this pit.

- 29/6/1869, John Long, aged 28 years, pitman. Killed by a stone falling down the shaft. At that time there was only one shaft at this colliery, sunk in 1860. It was divided into two parts; one part was for the winding of coal, men and materials, and to let the fresh air down the mine, and the other part was for pumping water and the foul air up the mine. John’s job was to make sure that everything was in order in the shaft. In those days the shafts were not lined (i.e. bricked) and loose stones were a constant danger and could be shaken loose by the vibrations of the cages going up and down the shaft. To view the walls of the shaft correctly, on his inspections John would have rode on top of the cage to give himself a better view. It looks like when he was doing this a stone dislodged and killed him.

- 10/6/1883, Edmund Bevan, aged 34, collier, fall of roof.

- 21/6/1883, John Simpson, aged 21, haulier, run over by trams.

- 28/7/1883, John Simpson, aged 21, haulier, run over by trams.

- 26/9/1883, W. Williams, aged 56, ostler, crushed by a horse.

- 19/12/1883, T. Simms, aged 16, collier, coal fell down shaft.

- 26/1/1887, Edward Smith, aged 14, fitter, fell from roof.

- 29/1/1887, Daniel Jones, aged 38, collier, fall of roof.

- 4/6/1887, Thomas Roberts, aged 60, repairer, fall of roof.

- 12/9/1887, Emlyn John, aged 34, collier, fall of roof.

- 30/4/1891, John Davies, aged 25, labourer, caught in machinery.

- 22/5/1891, Thomas Knighton, aged 40, labourer, fell.

- 10/7/1891, Thomas Jones, aged 62, labourer, fall of roof.

- 27/7/1891, Richard Hughes, aged 30, master haulier, run over by trams.

- 4/9/1891, Daniel Connell, aged 36, labourer, fall of roof.

- 8/9/1891, Thomas Henry Nills, aged 29, labourer, crushed by falling timbers.

- 22/10/1891, William Lock, aged 50, cropper, accident with surface wagons.

- 6/12/1892, Samuel Thomas, aged 38, collier, fall of roof.

- 8/7/1893, William Newman, aged 32, collier, fall of roof.

- 4/8/1893, Joseph Morgan, aged 43, collier, fall of roof.

- 23/12/1893, William West, aged 37, collier, fall of roof

- 24/1/1894, John Griffith, aged 55, ripper, fall of roof.

- 25/4/1894, George Marshall, aged 43, timberman, fall of roof.

- 18/9/1894, J.P. Reynish, aged 55, foreman, run over by locomotive.

- 10/11/1896, Edward Jenkins, aged 13, collier boy, run over by trams.

- 25/5/1897, John Morgan, aged 28, collier, fall of roof.

- 5/11/1898, William Edwards, aged 38, pitman, fell down shaft,

- 16/1/1899, W.H. Daley, aged 22, haulier, fall of roof.

- 6/5/1911, David Jones, aged 22, collier, fall of roof.

- 31/1/1914, William Button, aged 36, collier, fall of roof.

- 15/8/1914, Frank Oaten, aged 52, assistant repairer, fall of the roof.

- 1/8/1925, Albert Morris, aged 43, master haulier, crushed by trams.

- 13/9/1929, John Tierney, aged 45, haulier, knocked by a horse.

Some statistics:

- 1889: Output: 271,142 tons

- 1894: Output: 284,634 tons

- 1896: Manpower: 1,548

- 1899: Manpower: 1,584

- 1901: Manpower: 1,764

- 1902: Manpower: 1,710

- 1905: Manpower: 1,884

- 1908: Manpower: 1,835

- 1909: Manpower: 1,835

- 1910: Manpower: 1,118

- 1911: Manpower: 711

- 1912: Manpower: 1,600

- 1913: Manpower: 1,386

- 1916: Manpower: 1,898

- 1919: Manpower: 1,832

- 1920: Manpower: 1,682

- 1922: Manpower: 1,990

- 1923: Manpower: 2,104

- 1927: Manpower: 2,156

- 1930: Manpower: 575

- 1932: Manpower: 500

- 1935: Manpower: 915

- 1938: Manpower: 221 underground only

- 1940: Manpower: 312

NIXON’S NORTH COLLIERY

Mountain Ash, Cynon Valley

Sunk by John Nixon, the founder of Nixon’s Navigation Coal Company

(see above), with its history being the same as the Navigation Colliery.

The winding level at this pit was from the Seven-Feet seam level at a depth of 440 yards. The shaft diameter was 17 feet. The fan pit at this colliery was used as a standby for the Deep Duffryn Colliery until the 1970s.

Information supplied by Ray Lawrence and used here with his permission.

Return to previous page