Old Clough Colliery Situated in the village of Weir, Old Clough colliery was there before the village came into being as it is known today. As yet we don’t know for sure when Old Clough actually opened, it was however in existence when the first OS map was surveyed in 1844. The colliery was opened by John Ashworth of Hargreaves and Co. around 1834/5. A further document dating from the 1840s states that the company had then been in existence for 40 years and there are older workings in that area and one area is known as ‘ Coalpit Clough’. It was never a big pit throughout its long life which must have spanned well above 100 years. It never had any sort of mechanical haulage. The colliery itself was mostly worked in conjunction with the Old Meadows colliery. The Manager taking charge of both pits and men at the same time, flitting between the two. I don’t have much data for men employed during the early years but here is what I have.

- 1896 – Manager Gaythorn Bland. Under manager John Hey. 7 employed underground, 1 on the surface.

- 1913 – 8 underground 1 surface.

- 1920 – 8 underground 1 surface. Workforce broke down thus; 4 colliers. 3 Drawers. 1 Fireman. 1 surface. Output per day 10 Tons

The first proper reference we have of the pit, besides the map reference goes back to 1848:

Preston Chronicle 10th June 1848:

BACUP COAL PIT ACCIDENT.

On Tuesday last, an inquest was held at the Waterloo Inn Bacup, before John Hargreaves, Esq. Coroner, upon the body of Robert Lord, a coal miner, upon whom a massive piece of earth bad fallen on the previous Saturday, while he was at work in the Old Clough Colliery, a short distance from Bacup. On Saturday morning, another collier who was at work in the mine, upon hearing a scream, ran towards the spot and found the deceased lying under a large stone, which had fallen from the roof upon him. The stone was four yards long and seven or eight feet wide. He was. lying upon his face, the stone resting upon his head and back. The stool he had been sitting on had been thrown to one side as if he had endeavoured to make his escape.

A hole was dug underneath the stone, by which means the body was got out, but quite dead. It appeared that the roof was a dangerous one, as on the Tuesday previous another fall of some loose stones had taken place out of which the deceased was obliged to be loosened. The deceased had been told, “to prop the roof” and he had for that purpose, taken a piece of wood but he had neglected to put it up. The underlooker whose duty it was to examine the roof, had not done so since the Tuesday previous, and his reason for not doing so was, that there was not much work going on in the mine on the Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday. The deceased has left a widow and five young children to deplore his loss. Verdict accidental death.

If you are wondering why the pit was only working a few days a week, it was because of the trade depression in the textile industry that still prevailed in 1848 indeed which had prevailed for 10 years resulting in a resurgence of the Chartist movement and then the General strike of 1842 which we know as the plug riots. Many people in Bacup were heavily involved in the Chartist movement and the mass gatherings numbering into the thousands were almost a weekly occurrence all over Lancashire. Indeed during May 1842, 12,000 had attended a meeting on Deerplay Moor. There is also a reference to the riot act being read at a meeting in Bacup but as yet I cannot confirm the actual details. The strike itself caused the Bacup streets to be thronged by literally thousands. They started off from Cronkeyshaw Common in Rochdale, weavers and colliers alike, men and women, boys and girls. Gathering many as they marched through Britannia towards Bacup and turning weavers out of the mills as they went. Hardman’s Mill and Munns Mill were amongst those affected in Bacup resulting in the ring leaders being arrested. Many marched on over Sharneyford to Todmorden, thence to Littleborough and back into Rochdale. One reporter stated what a sad sight they made, girls who had marched all day in heavy clogs without hardly any refreshment trudging wearily back into Rochdale at the end of the day. The people of Bacup and Rochdale had on another day marched to Burnley and then to Blackburn and were confronted by the militia in both towns. They scattered at Blackburn and it appears they made their way homewards over the hills before finally trying to get the miners at Burnt Hills Colliery, Clowbridge to come out and join them. Again they were dispersed by the Burnley militia.

Even though the dreaded Corn Laws had been repealed the textile trade struggled to recover and even by 1848 people were wandering the streets of Bacup in groups collecting Alms and mills were still being turned out on a daily basis. The Preston Chronicle reported during May 1848, 3 months before the strike, that two of the mills at Edgeside Holme and Stacksteads had been working on short time and the weavers were living on a reduction of 15 to 20%. Numerous other mills in Bacup had been stopped for over a fortnight and upwards of 1700 hands were out of work. On the previous Wednesday, a collecting cart accompanied by almost 1500 persons went through the town past the Institutional Hall. The downturn in trade not only affected the mills but it also affected the pits that provided the coal and many of those were only working 2, 3 or 4 days a week out of the usual 6 days a week.

Old Clough worked the Lower Mountain or Yard mine as it was also called, which averaged 3ft in thickness. The coal extended right the way through the hill and the pit eventually became connected with Grimebridge and Nabb pits so there was no shortage of coal to go at. During the August of 1866, Benjamin Hey of Weir terrace was erecting a prop when a stone fell and broke his knee cap. In the April of 1876 John Hoyle 17, John Wood 13 and Richard Horsefall 14, turned up at the pit one Wednesday morning just as one of the colliers, James Roberts was about to go down the pit. They asked him if there was any work but he replied that there wasn’t and went off down the pit. He came back out of the pit shortly afterwards and found the cabin door had been forced open and a handkerchief containing bread and a bottle of tea had been stolen and he saw the boys running over the fields behind the cabin. PC Forbes was sent for and he went to arrest them. When caught, Hoyle said that he had gone behind the cabin and the other two had broken in so he had to follow them over the field. He was dismissed from the court but the other two were found guilty and sentenced to 21 days imprisonment. All fatal accidents have a profound effect and maybe all the more so in a small community and a small pit where everyone knows everybody else really well and probably has done all their lives. This happened two years following the theft of the bait and the tea. James Ashworth was 29 and lived at Weir Terrace. He had worked at the pit for a number of years and during the January of 1878, he was employed as a collier removing coal pillars, which is the most hazardous work in coal mining as you are finally removing the last natural support and allowing the roof to totally cave-in behind you. At quarter past two on the Thursday his drawer last went in to take a tub from him and he was expected to come out of the pit by 3 o’clock. James, however, didn’t come out of the pit and after they had waited for a while his drawer volunteered to go back in to see what was holding him up. They must have waited a while, indeed they must have gone home because his drawer didn’t find him till five o’clock. They found him lying on the floor with a large portion of the roof down and it looked to have caught him on the head and shoulders as he had several scalp wounds through his hair. The inquest came to the conclusion that he had been removing the top coal but hadn’t had sufficient supports set, it gave way and between 5 and 6 cwt fell on him. James left a widow and two small children. He was a member of Doals Baptist church and had been actively working in the Sunday school for several years.

In August 1887 another serious accident occurred when J. Brannon who also lived in Weir was leaving the pit one Wednesday afternoon. Just before he could see daylight the roof fell on him, striking his foot and knocking him down. Though he tried to rise he found he couldn’t and so had to shout for help. He was got out by the others and taken to Manchester Royal Infirmary where it was found he had 2 broken bones and another two partly crushed.

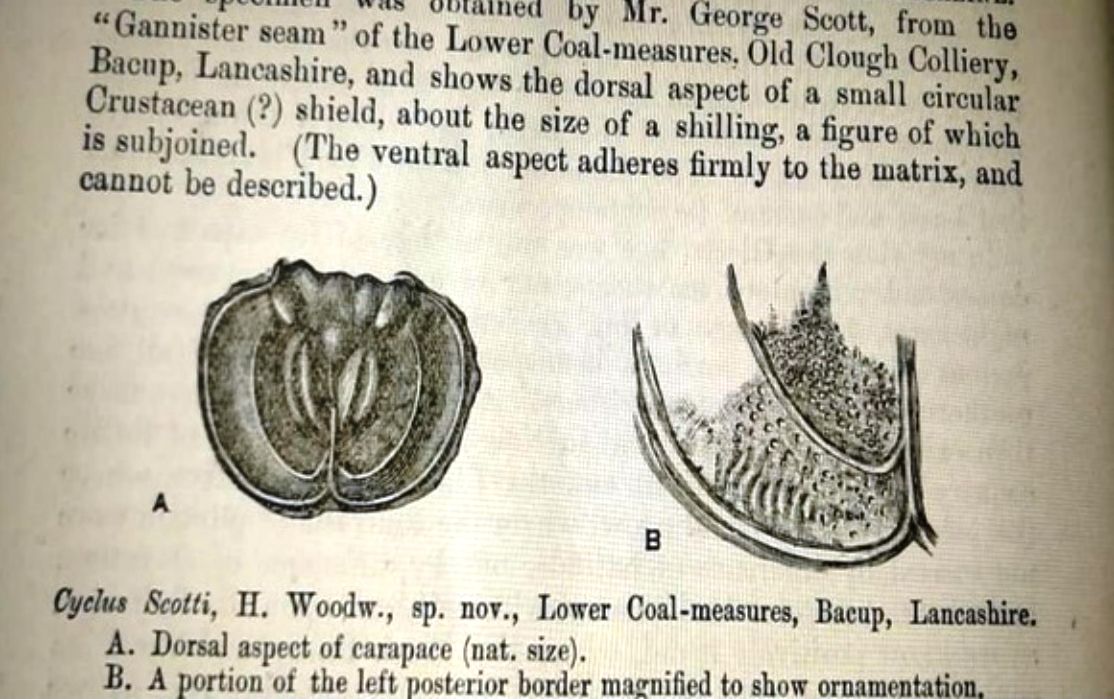

An article appeared in a geological magazine in January of 1893. Mr. George Scott found a new British species of Cyclus in the Ganister seam of the Lower Coal Measures at Old Clough Colliery, Bacup. The specimen was named “Cyclus Scotti”. These are a type of Crustacean, like a crab and obviously, this was a fossilised one.

As previously mentioned Gaythorne Bland was the manager at both pits. He died aged 77 in February 1925. He began his mining career as a drawer at Old Meadows. He later moved to Accrington and Baxenden before going to America for a number of years to work in the coal industry there. He returned in the late 1890s where he took a post at Crawshawbooth for Hargreaves Collieries before becoming manager at Old Clough and Old Meadows pits. He had retired from work but went back to work on the coal staithe and started on the 9th of December 1920 aged 68 putting empty tubs on the chain. I seem to recall reading more on the subject of his retirement from being the manager but can’t put my finger on it at the moment.

On the subject of the proximity of Old Clough to Grimebridge an old entry in the diary of Joe Hunter who was Manager at the two pits from 1920 states that on the 14th of October 1920, Henry Schofield was driving a heading through some rough low coal to meet up with the Grimebridge old chain road.

More follows from Joe’s Diary; In November Weir mill started to take Old Clough coal, but a week or so later the Weir Mill custom was given to Sharneyford Colliery, 4 to 5 tons a day. Holes began to appear in land belonging to Hay Slack due to removing pillars of coal during 1922 during which time C. Crook is the Fireman at Old Clough. Irwell Springs print works were in negotiation about taking water from the pit, the water loose ran under the Weir Hotel but there was a bit of trouble finding it. Two surface workers; Turner and Coates tried from the 27th of April to the 3rd of May but couldn’t find any trace of it.

Henry Tattersall was engaged as a collier on 1st of May 1824 but the drawers refused to draw for him so Joe Hunter had to have a meeting with Mr. Bolton (Director of Hargreaves Collieries) and Mr, Mitchell about the situation. The outcome was that Henry was transferred to Sharneyford Colliery on surface works, he later got on coal getting at Old Meadows. This at first looks quite a petty situation but there could be more to it than meets the eye. If a collier was needed, then it was usual practice to put the lad who had been drawing for the longest period of time onto coal getting and it looks like this possibly hadn’t happened so the drawers took action. Not all colliers stuck the job even if they had been a collier at another pit previously for instance Henry Greaves was set on at Old Clough as a collier on January the 12th 1925, he gave up the job on the 14th and a week or so later went to Old Meadows on day work. Another example of drawer rebellion was found but this time at Old Meadows during March of 1925 when Henry Hargreaves packed in owing to a section of the drawers demanding that he should commence behind them as a drawer.

There was also a large turn over of drawers at all the pits but Old Clough and Old Meadows, in particular, appear to have gotten through an awful lot. For example, F. Gregory started drawing at Old Clough in March, he finished the same day, he did 2 days in one; his first and last! However a further report is that he left without notice during August, so he must have come back for a second bite of the cherry. Another drawer, Horace Nuttall got a start at Old Meadows during December but he “jacked” the same day so they started him at Old Clough the following day and…jacked the same day.

The colliers got dissatisfied with their conditions so there was a meeting with an arrangement. A couple of weeks later the drawers had to be reprimanded for crossing through safety fences and going exploring old workings, Joe Kennedy fixed the problem by giving them more work to do.

In 1926 the colliers notice to strike ended on April 30th and the following day the only people working at both the pits were the Firemen and Clerks. The General strike was declared a few days later on the 4th of May. The Firemen worked through the strike and at least some work was found for them up at Old Clough they were repairing the air shaft and office. The first colliers back after the strike was on August 17th. It doesn’t appear that things went back to normal for quite a while at both pits, there was falling out and a laxness of work. On October 1st, 3 drawers came out in dispute at Old Clough so Joe just gave them their cards and sent 2 fresh drawers up and then 2 further ones were set on, Mcmanus and McHugh. McHugh was sacked the following August. Some drawers just didn’t like it because it was too low for them, H. Salmon was one such and he threw the towel in 1927.

Some of the Old Clough take was given to Grimebridge Colliery and on March 23rd 1928 Old Clough colliery was transferred to be part of Grimebridge Colliery and T. A.. Ashworth assumed responsibility for the pit. T. A had started his working career as a ‘Half timer’ at Corner Dye Works. There had been a slump in the coal trade, as in most trades and due to the economic position of the mines, Joe Kennedy was demoted from Manager to Undermanager on the first of May.

Old Clough finally closed during 1935 and after over 100 years you would think that was it but it wasn’t. Quite a few local mines didn’t survive the 1930s, Good Shaw Hill and Gambleside also closed and on the eve of Nationalisation, the day many thought would never come, Stacksteads colliery closed. January 1947 dawned with the Rossendale coalfield comprising of Grimebridge, Nabb, Old Meadows and Deerplay being Nationalised and two pits, Sandy Road ( East Lancashire Brick Co) and Clough Head (Temperlays’) continuing to operate on a licence to the new NCB. Hill Top Colliery was a completely new project that started shortly after the pits were nationalised. Nabb Colliery had been seen before nationalisation as a long life pit and was the only one that Hargreaves invested in, to the tune of building pithead baths for the men. Unfortunately, history never works out as you think it might and it was the first local pit to fall under the hammer and closed by the NCB in 1954.

The entrepreneurial spirit is sometimes born out of adverse circumstances. The Croppers had been mining and farming for generations; Jimmy Cropper had been a Fireman at Nabb pit and his father had told him that there was still a lot of coal to get beneath the land they owned at Carr Farm in Dean village. Jimmy had re-opened the Old Dean pit by starting a new one called Carr Drift, situated a couple of hundred yards away from the old pit entrance. At its peak, it employed 30 men. He also opened up another pit up behind the village working along Turn Hill ridge. In the late 1960’s he turned his attention to the coal left at Old Clough, which would have been too far underground to have been worked from Carr drift.

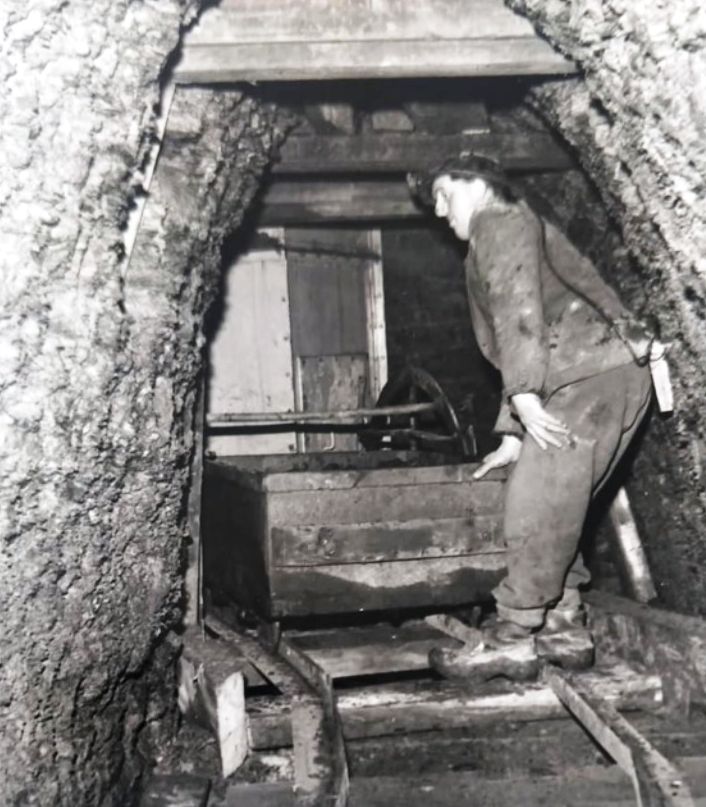

Doals Pit 1960s. George Heys with a tub. The elevator which took the coal to the surface was in a square box behind the tub. You can see the tippler behind the tub also.

In 1966 the workings at Old Clough pit were reopened from Doals No 3 farm. To get planning permission there had to be no visible signs of the pit to blight the landscape so the pithead itself was situated in the barn and farmhouse. All that could be visibly seen different from the buildings was what looked like a blue chimney, this actually contained the small elevator. Coal was brought along the underground roadways to below the barn and was then wound up into the barn via a small shaft. His NCB granted mining licence restricted him to only 7 employees, all the coal was won by using compressed air picks. I have been told quite a few stories in years past from men who worked there. Sadly I never wrote them down and many were forgotten by the time we were told to go home and the Taproom lights were turned off.

If my memory serves me correct, the reason for the restriction on the numbers of employees, though at small mines numbers were restricted to 15 unless you employ a certificated manager, then you can employ 30. The restriction to 7 could have been because the second means of egress out of the pit was up the air shaft at 140 ft deep and not equipped for man riding. But I may be wrong, but this would certainly have a bearing on the decision. I also understand that the reason that the pit closed was down to the decision made by HM. Inspector of Mines. Coal had been worked to near the air shaft and had made the ground unstable around the shaft, but I may be wrong. I’m sure somebody will know and correct me?

N.B. The pit closed due to the main airway collapsing.

Information from:

John Davies, Various Newspaper articles, HM. Mines Inspectors Reports, Conversations with Old Colliers, Tommy Helm.

Clive Seal

Return to previous page