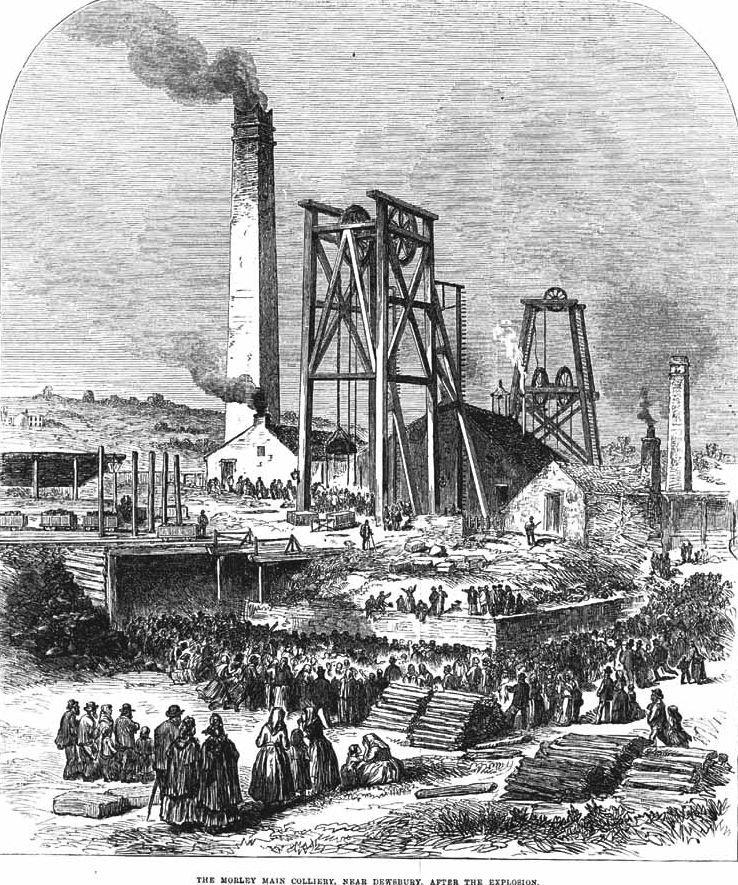

MORLEY MAIN. Leeds, Yorkshire. 7th. October 1872.

The colliery was the property of William Ackroyd Brothers, with Jonathan Simpkin as the manager and was between Dewsbury and Leeds. It was known as the Deep Pit where 500 men were employed. One hundred and fifty men went down in the morning with 50 to 60 into the lead workings where the explosion took place which took the lives of thirty-two men in the pit and two more died later from their injuries in Leeds Infirmary. The seams at the colliery were fiery and the explosion came like a clap of thunder and was totally unexpected. The seam of coal in which the disaster occurred was called the Middleton Main or Deep Coal at a depth of 156 yards and it was worked by pillar and stall. There was an upcast and a downcast shaft at the colliery and a shaft from which the stone “coal” was worked was sunk to the Deep Coal and delivered the ventilation to the seam. The ventilation was from two furnaces, a large one and a small one which was 20 to 30 yards from the bottom of the upcast shaft. There was dumb drift and the return air passed into the shaft on the same level with a wall built into the shaft about eight feet high. The furnaces were fed with fresh air and on the day of the accident, there were 18,000 cubic feet per minute of air passing over these furnaces.

There were a large number of faults which threw the coal 35 yards upwards and the roof near these faults was not good and it was known that they gave off gas but the roof in other parts of the mine was good and hard The manager allowed the men to fire their own shots in the mine. The mine employed about 250 people and 42 horses were below ground at the time of the accident.

Mr. Simpkin went down the colliery at 6 a.m. on the morning of the disaster and saw the deputies and night men come out and Allen reported to him that there was a little gas on the north side of the pit. Simpkin went down at 8.30 a.m. and examined the south side and started to come up at 1.30 p.m. when he felt a suck which did not put out his light. He was with a labourer John Holmes and the air returned to its normal course. They went back into the pit and met Berry and one or two others and went up the north side.

They went on for about 100 yards and were told that it was all right. They returned to the pit bottom where a boy called out that the pit had fired in the Andrew. Simpkin, Holmes, Berry and some others went along and about 700 yards up the brow they saw that some iron sheeting had been knocked down. Dirt was all knocked down and the sheeting was blown towards the shaft. The explosion had affected a district known as Andrews Road and the damage was confined to this district.

The men who died were:

- George Hardy aged 22 years.

- Thomas Seddon, aged 32 years, married with three children.

- James Hardy aged 51 years, married with ten children.

- Wiliam Parks aged 26 years.

- George Parker aged 16 years.

- Joseph Singleton aged 14 years.

- Henry Broadbent aged 14 years.

- John Thomlinson aged 33 years, married with a child.

- Emanuel Page aged 32 years, married.

- George Carson aged 16 years.

- Thomas Auty aged 43 years, married with three children.

- John Powell aged 49 years, married.

- James Howarth aged 37 years.

- James Pickersgill, married with six children.

- James Butterfield aged 14 years.

- Walter Earnshaw aged 16 years.

- Robert Headley aged 16 years.

- William Marsden aged 51 years, married with two children.

- John Roberts aged 50 years, married with three children.

- John Addison, aged 32 years, who left a widow.

- William Pickersgill aged 17 years.

- Henry Townsend aged 36 years.

- Matthew Spence aged 36 years, married with three children.

- Noah Preston aged 19 years.

- John Mitchell aged 35 years, married with three children.

- George Hurst aged 38 years, married with nine children.

- Joshua Teasdale, aged 35 years.

- George Ball aged 31 years, married with two children.

- George Preston aged 45 years, married with three children.

- George William Wroe.

- Mark Wroe, aged 28 years, married.

- James William Yates aged 14 years.

- Joseph Armitage aged 41 years, married with eight children.

- John Ratcliffe aged 58 years.

Some of the survivors were:

- Charles Barraclough,

- George Manley,

- George Preston,

- William Smith,

- Thomas Hartley and

- three men, Blizzard, Thornton and Grant.

Eleven horses were also killed.

The inquest was held by Thomas Taylor, Coroner, at the Royal Hotel in the town to where the bodies had been taken. All interested parties were represented. The Inspector of Mines, Mr. Wardell inspected the explosion area after the disaster and found that the goaf was not ventilated and either the firing of a shot or a fall of roof, displaced gas into the intake airway which was ignited at a naked light.

It was proved in evidence at the inquest that pipes, matches, lamp keys and nails had been found in the clothing of the victims and it was also stated that on the morning of the explosion there was a strong smell of tobacco by a deputy at the extreme ends of the workings but there was not report of this violation of the rules by any of the officers at the mine.

Rule 30 was read:

No person shall go into the workings with a naked lamp. No person shall smoke tobacco or light a naked candle in any place where safety lamps are ordered to be used.

Mr. Wardell went on to say:

I have a strong conviction and I take this opportunity of expressing my opinion, one advanced many times before, that the use of gunpowder in mines giving off gas to such an extent as to require the use of safety lamps, is likely to tend to such disastrous consequences as having brought us here this day. I am strongly of the opinion that had the goafs and endings been thoroughly examined as far as man could go into them, gas would not have accumulated in large quantities. I would suggest the desirability of discontinuing the use of naked lights in the colliery altogether, excepting the shaft and the bank headlights at the bottom. I would recommend that the ventilating staple, through which the whole of the air from the district returns should be enlarged at least the seam sectional area as the main airways that no more powder be used except in the stone drifts and in the coal at night when the colliery is at work, and then to by properly authorised persons, and that in consequence of the comparatively short rarefied column of air in the upcast shaft, it is more desirable that mechanical ventilation should be substituted for the furnace, and I think the fan be the best-known means.

The jury retired and returned the following verdict:

That we have come to the conclusion that the deceased came to their deaths by an explosion accident caused by a large accumulation of gas in the goaf at the top of the second pair of north endings, which gas appears to have travelled to the naked light in Hardy’s jig. But we consider that there has been carelessness on the part of some person or persons in charge of the workings, and we are of the opinion that more care is necessary in the ventilation, to clear away the gas that accumulates in the goafs.

Information supplied by Ian Winstanley and the Coal Mining History Resource Centre.

Return to previous page