AUCHENGEICH. Chryston, Lanarkshire. 18th. September, 1959.

The colliery was situated about seven miles northeast of Glasgow and was in the No.3 Central West Area of the National Coal Board. The manager was Mr. J.F. Smellie with Mr. A. Pettigrew as undermanager. The Group Manager was Mr. C.M. Inglis, the deputy Area Production Manager (Operations) Mr. J. Lawrie and the Area Production manager Mr. J. R. Cowan. The Area Manager was Mr. D. Lang. The disaster occurred in the No.2 Pit and the resulting fire cost the lives of forty-seven men.

The mine was known to be gassy and had two shafts which went to the No.2 Pit workings where the accident occurred, at a depth of 360 yards. The downcast shaft had two hinged gratings known as Needles fitted at 150 yards where there was an inset for the No.1 Pit workings in the Meiklehill Wee Seam. The cages were not normally wound below this point. At the time of the accident 830 men were working in the mine which produced about 730 tone of coal per day. In the No. 2 Pit workings there were 340 men with about 140 on each of the day and back shifts and 60 on the night shift. The daily output was about 380 tons from the Meiklehill Main Coal and the Kilsyth Coking Coal Seams. The night shift men ascended between 6 and 6.30 a.m. and the day shift men were lowered between 6.30 and 7 a.m.

In the No.2 Pit workings where the accident occurred, there were two main roads running south and parallel to each other to the workings of the Main Coal and the Coking Coal Seams. The intake airway was used for the haulage of coal by endless rope and the first 925 yards of the return airway for a man-riding haulage system. There were connections at the pit bottom and there was also a crosscut with air separation doors which was commonly known as Johnstone’s Crosscut about 1,125 yards inbye near the No.6 bench which was the back of the haulage road leading to the Coking Coal Sections. The return airway from the Coking Coal Sections crossed the main intake airway by an overcast and then joined the main return airway between these connecting crosscuts. The booster fan at which the fire occurred was in the return airway, a little further outbye. The intake and the main haulage road were supported by steel arched girders which were twelve feet wide by nine feet high from the bottom of the pit to Johnstone’s Crosscut and twelve feet by eight feet from there to the No.6 Bench. The return and the man-riding road was steel arched with timber lagging which had not been fireproofed. The arches in the return were thirteen feet high for the first 350 yards from the pit bottom and ten feet by eight feet for the next 200 yards, eleven feet by nine feet for the next 500 yards to a bend of the road just beyond the inbye terminus and the man-riding haulage and finally an average of twelve feet by eight feet beyond that point.

The system of ventilation consisted of the intake air to the No.2 Pit workings being split at the No.6 Bench to provide separate intakes for the Main Coal workings and the Coking Coal sections. The return air from these sections came together at No.5 Bench and then passed through the booster fan which was about 40 yards outbye at a point 570 yards from Johnstone’s Crosscut and about a mile from the pit bottom. The exhausting fan at the surface was electrically driven and produced about 160,000 cubic feet of air per minute at 5.4 to 5.5 inches water gauge. a standby fan had a similar capacity.

The booster fan was of a double inlet, forward bladed, centrifugal type with a 45-inch diameter rotor driven by a flat belt. The rotor shaft was carried on two white metal bearings, oil ring lubricated and each with an oil capacity of six pints. The cambered or “crowned” fan pulley was 22inches in diameter, 12 inches wide and overhung the bearing. The fan was driven at about 540 revolutions per minute by a 100 horsepower motor, flameproof, slip-ring induction motor running at 730 revolutions per minute. The power supply was three-phase, 50-cycle, alternating current at 440 volts. The motor pulley was also “crowned” and was 16 inches in diameter and 15 inches wide. The pulley centres were 15 feet apart. The fan drive as fenced on the near side with a one-inch steel aperture mesh supported from an angle iron frame secured to the sidewall of the fanhouse. A timber covering or “catwalk” was made from nine inch by two-inch battens was placed over the belt to make access easier to the nearest fan bearing.

The transmission belt was seven-ply and twelve inches wide of a type known as balata belting which was made of folded high tensile cotton duck and balata gum, neither of which was fire resistant. The belt travelled at about 3,200 feet per minute if there was no slip. The fan was in the fan house in the main return airway and the outlet casing was mounted in a brick wall built across the roadway and with brick wall fairings to smooth the airflow into the inlets of the fan. The motor was mounted on three slide rails and could move about seven inches so that the belt could be tensioned; the circuit breaker and the rotor starter for the motor were in the in crosscut next to the motor.

A water gauge and an automatic indicator of the water gauge were placed near the haulage engine at the intake end of the crosscut to indicate and record the ventilation pressure between the intake and the return airways. Three wooded doors in the by-pass road were designed to open automatically by the change in the ventilation pressure in the event of a fan stoppage.

The sides of the roads inbye of the fan to the junction with the by-pass road were brickwork and the roof was supported by steel girders. Outbye from the fan the left-hand wall was brick and on the right-hand side there was a brick wall on which some wooden props were set to support the roof which were set to roof girders. The girders on the sides were lagged with wood but the wood had not been fire-proofed.

The man rider was an endless rope system with each car or bogie attached to the rope by an integral screw clip. The train was made up of four bogies, each seating twelve men in three compartments with seats of four, two facing each way. The electrically driven engine was housed in the return airway and provided with protection against overrunning and each end of the haulage and against excessive speed. The position of the bogies was shown on an indicator and by a warning stoplight.

The main telephone switchboard was in the lamp room at the surface with lines to the colliery office, the engineers surface workshop, the winding engine rooms, the pit head and down the shaft. The line from the surface to the upcast pit bottom ended in a small switchboard in the pumphouse connected to instruments in Johnstone’s Crosscut, No.6 Bench and other points inbye. Conversations between any two points could be overheard on other handsets. There was no telephone communication with the man-riding haulage system.

At about 6.25 a.m. on Friday 18th September, 1959 after most of the night shift had gone up and before the day shift came down, A. Paton, the night shift engineman in charge of the man-riding haulage, was waiting to be relieved by T. Campbell in his engine house near the upcast pit bottom, when he noticed a slight haze and a very slight smell of something burning. He was not worried by this and he went to meet the first cage of the day at the pit bottom containing the day shift men at just after 6.30 a.m. One of these men was J.H. Dickson, the day shift assistant overman. Paton drew his attention to the haze and smell. Dickson was suffering from a cold and could not smell anything but he sensed what he called “a king of heat” in the air. He decided to investigate inbye and told an oncost (day-wage) worker to inform R. Boyd, the day shift overman, when he came down the pit. Paton then went back to the engine house and ran the first train down the man-riding haulage road. Many of the men on that train gave evidence about the haze in the pit bottom and some sensed that all was not well inbye but none of the men seemed to have been alarmed. The train left at 6.40 a.m. with Dickson and about seven others. The normal journey time was about eight minutes so they must have arrived at two or three minutes after 6.45 a.m. There was no appointed guard on the train but it was signalled back to the pit bottom. Some of the men on the train said that the haze was slightly thicker at the inbye terminus that at the pit bottom but they were still not alarmed. It was the usual practice for the en to travel along the return airway to their working places but on this occasion Dickson decided that all the men should accompany him through Johnstone’s Crosscut into the intake airway. The men followed him and arrived at the fan about 7 a.m.

Dickson went alone through the doors at the back of the No.5 haulage engine house into the fan house and found flames rising from the fan belt which was burned through and lying on the floor. He saw that the belt was around the fan pulley and that the flames were being drawn into the fan casing. Others followed Dickson into the fan house and saw flames coming from the fan outlet and into the return airway at about 7.05 a.m.

Meanwhile, Boyd, the day shift overman who was down the pit about 6.50 a.m., had received Dickson’s message and had gone down to the main switches near the downcast shaft with the intention of switching off all the electric current inbye. He was uncertain about the switching arrangements so he told D. Kirkpatrick, a pump maintenance man, who was conversant with the switchgear to cut off the current. To make sure that this would not affect the No.1 Pit workings, Boyd decided to telephone an electrician on the surface. While he was trying to do this, he heard Dickson on the telephone saying that the fan was on fire.

Thornton, an electrician, had reached the pit bottom and Boyd sent him to the main switches to check that the current to the fan was off. Thornton went to the switches and telephoned Dickson asking him to cut the supply to the fan motor. Boyd had told an oncost worker to give a message to Campbell in the engine house and this message was heard by the conveyor beltman. The message was that no one was to be let down the man-riding haulage until further notice. In evidence, Boyd said that he intended that any of the men in the haulage should be withdrawn but the message was misunderstood. He walked inbye to the intake airway and on the way met a brusher who had been sent by Dickson to Johnstone’s Crosscut to stop any men going into the return airway. Boyd felt he had stopped all the men going in, so he took the brusher with him to the fan which he reached shortly after 7.30 a.m.

Paton, on receiving the signal, started to haul the empty train outbye but was then relieved by Campbell at about 6.50 a.m. Paton walked to the cage and out of the pit. On the surface he told D. McKinnon, the chief engineer and A. Pettigrew, the undermanager that there was a haze in the return airway. Pettigrew suspected that the haze was being caused by the fan belt which, as he knew, had been giving trouble during the night. He went to the lamp room and telephoned a warning to the overman of the No.1 Pit workings that the booster fan might not be working. He had just finished the call when Dickson called the lamp room. Dickson told Pettigrew that there was fire in the fan house and that hoses and extinguishers were urgently needed. McKinnon and Pettigrew informed the manager and went down the upcast shaft about 7.10 a.m. taking with them a new fan belt which McKinnon had earlier sent for. It did not occur to then that the men in the no.2 Pit return airway were in imminent danger. They were anxious about the ventilation and their sole purpose was to put out the fire and restart the fan. At the bottom of the shaft they encountered dense smoke and Pettigrew saw a number of the day shift men waiting to go up and he assumed that all the men from the return airway were there. He went down the intake airway with McKinnon and D. McAuley, a mechanic.

The first train returned to the terminus about 6.55 a.m. Forty-eight men then boarded the train to go inbye. According to the engineman the train left at 7 a.m. Thomas Green, the sole survivor of the men on the train, said the haze thickened very slightly during the journey to the terminus. When the train arrived, none of the men left the terminus since, just as they arrived, a thick blanket of smoke came along the return airway towards them and the men, by common consent decided to get on board the train again.

Campbell received the signal to haul outbye and started to do so but then he had signalled to stop and start the train three times in quick succession but the train eventually got underway and did not stop until it was near the outbye terminus. Thomas Green remembered the train stopping once only. This was at the top of the 1 in 5 gradient when it stopped so that one of the men who had slumped off the bogie could be pulled back into his seat. Green said the smoke was very thick indeed and he covered his nose and mouth with his jacket as best he could. He was sitting at the outbye end of the train and when it stopped before reaching the terminus, he got off and stumbled along until he was overcome after passing the gate at the outbye end of the man-riding haulage road where he was rescued. None of the other forty-seven men on the bogies escaped. As they were found, it was evident that forty-three of them had been overcome as they sat on the bogie, one appeared to have fallen from the train about 300 yards inbye and only three seemed able to have made an attempt to escape and they had died quite close to the train.

Earlier, as the in-going train was nearing the inbye terminus, Campbell had received Boyd’s message about not letting the men down the haulage. He thought the message meant that his authorised guard and any men who remained on the bogies were to be withdrawn. He was not unduly worried at this time and when he received the first signal to bring the bogies outbye, he assumed that only the guard was on board but the signal to start and stop lead him to believe that there was something wrong. The train was about halfway out when the haze in the engine house turned to thick black smoke and he could not see the train position indicator. Conditions became worse and Campbell could stay no longer and was faced with the difficult decision of whether or not to stop the train. He did not know how many men were on the train and it passed his mind to leave the engine house without stopping the train which would have continued to the outbye engine house and cut out automatically. He was slowing down the engine when he heard a voice and he decided to stop the bogie for fear of running down any men who were trying to escape on foot. He brought the train to rest 100 yards from the terminus. By this time, about 7.15 a.m. Campbell was almost overcome but was able to make his way out through the separation doors near the Main Coal haulage engine to the intake air and from there he later rode in the downcast shaft to the surface.

A number of men were waiting near the outbye terminus for a third train to take them inbye when the haze thickened to smoke. They went into the fresh air which was leaking through the separation doors in a connection a short distance outbye but while they were waiting they heard something moving. Some of them went back into the smoke and found Green groping around in zero visibility. They took him to the upcast shaft bottom. G. Brown, the onsetter at the bottom of the upcast shaft, was also overcome and was rescued and taken into the air intake and then up the downcast shaft. Tribute was paid to the parties who rescued these two men at the inquiry.

After the discovery of the belt blaze, Dickson stopped the motor and hurried to the No.5 haulage house, about 50 yards away and picked up a fire extinguisher. He returned to the fire but found that it would not work. He instructed A. Cunningham, a deputy, and others who had followed him to the fan, to try to smother the fire with sand and stone dust while he went to the phone. He contacted the surface from the No.6 Bench, about 100 yards from the fan and asked for extinguishers to be sent down. He also told the surface that the fan was not working. He collected another extinguisher from the No.6 transformer house but this also would not work. He did not look for any more but went to the phone at the No.6 Bench and called for extinguishers and hoses. He had to wait a moment or two before the pumpman on the switchboard at the bottom of the shaft connected his call to the surface.

Dickson then went to the No.5 Bench to prepare the hydrants for the hoses but found that they had been blanked off. There was a hydrant 300 yards away in the No.6 roadway but he thought this was too far away and decided to take the hydrant and fix it to the water range at the No.5 Bench. He was assisted in this task and the hydrant was ready when the hoses arrived sometime later. At about 7.15 a.m., he contacted the surface and spoke to D. Gray, a general duties man, in the lamproom, and asked for the Rescue Brigades to be summoned. Up to this time, Dickson had seen only the inside of the fan house.

After the train had left, two deputies, M. Lynch and J. Roe, had walked down the return airway, through Johnstone’s Crosscut and had arrived at the fan shortly after Dickson. They had seen the fan casing and the oil burning at 7.05 a.m.. Roe helped Lynch to put stone dust on the fire for a short time and then went through the three by-pass doors. Lynch had local fire service experience, tested the extinguishers that had failed when Dickson tried to use them and found them unworkable. He followed Roe through the doors and both men saw flames coming from the fan outlet and striking the roof on the right-hand side of the road between the fan and the safety fence. F. McDonald, a brusher, said that at 7.15 a.m. the belt had been reduced to ashes, the fan casing was alight and when he went through the doors shortly afterwards, he saw fire in the roof outbye of the fan.

Boyd reached the fan shortly before 7.30 a.m. when the fire in the fan was still burning but when he went through the doors, he saw only smouldering in the roadway between the fan and the safety fence although the return airway was on fire outbye of the by-pass junction. When Pettigrew went through the three doors a few minutes later, he found a fire and a fall of roof at the junction.

There was some uncertainty as to the time when the hoses were taken down the pit but it was about 8 a.m. or a few minutes after. The equipment reached the scene of the fire between 8.20 and 8. 30 a.m. and it was quickly put into service by men under the supervision of Pettigrew. At first only one hose was used but later equipment was brought down by the Rescue Brigade and two more were brought into use. Fire fighting continued throughout the day and for some time they were able to control the fire but after a time they were hampered by falls of roof which occurred as the wooden lagging above the girders were burnt away.

It was much later in the morning that Pettigrew learned of the men trapped in the return airway and he instructed R. Harvey, the safety officer, to carry out a check of all men in the pit. This was done and Harvey went to the surface where a similar check was made by the manager at about 8 a.m. As a result of these checks, it was found that forty-seven men were missing.

At the surface, soon after Pettigrew and McKinnon went down the pit, Kirkpatrick, the pump maintenance man, who had learned of the fire from Thornton, the electrician at the bottom of the pit, reached the surface with J. White, a roadman, and began to assemble hoses and extinguishers. The manager prepared to go down the pit and he had not at this time, anticipated that lives were in danger. On his way to the lamproom at about 7.20 a.m. he saw Green being brought out of the pit unconscious and recognised that something was very seriously wrong underground. He realised that it was unsafe to use the upcast shaft and immediately gave instructions for winding in the shaft to stop. He told White to tell the engineman of the downcast shaft that the needles were to be lifted at once and then to go down the pit himself and see that the lifting operation was properly carried out and the job done quickly.

The fire fighting equipment collected by Kirkpatrick and White was waiting to go down the shaft when the needles were lifted. The banksman, T. Montgomery, said White descended at 7.35 a.m. and the needles were lifted and the rope lengths adjusted by a drum clutch to allow winding down to the pit bottom. The manager telephoned C.M. Inglis the Group Manager before contacting the Rescue Brigade and the Area General Manager and B. Spencer, H.M. Senior District Inspector of Mines and Quarries and L. Cheesborough, H.M. District Inspector were informed and quickly arrived at the colliery.

The call was received at the Coatbridge Rescue Station at 7.40 a.m. and the first team left at 7.45.a.m. and arrived at the colliery seven and a half miles away at 8.a.m. The second team followed ten minutes behind. After a briefing by the manager, the first team of five men descended at 8.08 a.m. and immediately set up a fresh air base on the intake side of the pair of separation doors nearest the man-riding haulage, wearing self-contained breathing apparatus they made a preliminary inspection and reported that the atmosphere was very bad, they had been unable to see anything but had stumbled on a body. The team returned and recovered the body. Artificial was given for about half an hour but without success.

In the meantime the second team went into the return airway and remained for fifteen minutes reporting that conditions were no better and they came out with some of the team distressed by heat. The atmosphere was full of carbon monoxide which after tests, was determined at 0.4 per cent which would cause death in a minute or two. From 9.30 a.m. onwards the rescue teams made regular examinations along the return airway near the shaft and took air samples. The Superintendent looked into the return airway and decided that conditions were so bad that it was not a justified risk of life to send men in. all hope was lost for the men trapped in the airway. Signal bells were heard about 4.30 p.m. but it was discovered that the signal had been caused by a fall of roof.

The operations went on and it was realised that the fire was not being brought under control and there were indications that methane was building up in the mine and R.J. Evans, H.M. District Inspector advised that all men should be withdrawn. This was done with the agreement of all parties. Hoses that had been laid in the downcast pit bottom were brought into use to start flooding the valleys in the intake and return airways near Johnstone’s Crosscut and to seal off the fire.

The men who died were:

- Alexander Morrison Beatie aged 26 years, roadsman.

- Thomas Bone aged 27 years, beltmen.

- Francis Broadley aged 38 years, developer.

- Matthey McIiwain Cannon aged 38 years, stripper

- William Brynes aged 54 years, coal cutterman.

- Walter Clark aged 61 years, back brusher.

- Henry Clayton aged 62 years, train guard.

- Robert Conn aged 30 years, back brusher.

- Andrew Crombie aged 42 years, oncost worker.

- James Devine aged 39 years, shotfirer.

- Andrew White Docherty aged 43 years, coal cutterman.

- John Duffy aged 39 years, shotfirer.

- Francis Jones Fisher aged 49 years, shotfirer.

- Martin Fleming aged 51 years, stripper.

- Michael Fleming aged 47 years, shotfirer.

- Richard Hamilton aged 48 years, stripper.

- James Harvey aged 44 years, stripper.

- Patrick Harvey aged 33 years, developer.

- Edward Henery aged 61 years, stripper.

- George Jackson aged 21 years, spare stripper.

- Francis Kiernan aged 26 years, beltmen.

- Peter Kelly aged 40 years, stripper.

- William Lafferty aged 39 years, stripper.

- Alexander Todd Lang aged 35 years, stripper.

- William Leishman aged 65 years, oncost worker.

- Gerald John Martin aged 34 years, shotfirer.

- John McAuley aged 42 years, back brusher.

- Robert McCoid aged 55 years, stripper.

- Joseph McDonald aged 53 years, stripper.

- Denis McElheney aged 49 years, developer.

- George Wilkie McIntosh aged 58 years, shotfirer.

- Andrew McKenna aged 41 years, deputy.

- Peter McMillan aged 55 years, shotfirer.

- James McPhee aged 54 years, shotfirer.

- William Meechan aged 22 years, oncost worker.

- John Muir aged 38 years, oncost worker.

- John Mulholland, Senior aged 50 years, stripper.

- James Nimmo aged 32 years, oncost worker.

- Aaron Price aged 50 years, stone worker.

- Robert Price aged 47 years stone worker.

- Alexander Sharp aged 34 years, stripper.

- John Shelvin aged 46 years, oncost worker.

- William Skilling aged 53 years, oncost worker.

- John Mack Stark aged 23 years, stripper.

- Thomas Stokes aged 32 years, oncost worker.

- Donald Cameron Weir aged 30 years, roadsman.

- George Thomas Thompson McEwan aged 20 years, oncost worker.

The inquiry into the causes and circumstances attending the underground fire which occurred at Auchengeich Colliery, Lanarkshire, on 18th September 1959 was conducted by T.A. Rogers, C.B.E., H.M. Chief Inspector of Mines and Quarries at the Justiciary Court, Glasgow on the 4th January 1960 and sat for ten days until the 15th January. The final report was presented to The Right Honourable Richard Wood, M.P., Minister of Fuel and Power in May 1960.

The inquiry heard evidence from eighty-five witnesses and all interested parties were represented. The following conclusions were reached:

1). The fire originated in the balata transmission belt of the electrically driven fan in the return airway from the No. 2 Pit workings. The fire was caused by frictional heat generated between the rotating motor pulley and the belt, which had left the fan pulley and jammed near it. Flame from the belt ignited the oil vaporised from the fan shaft bearings and oily deposits in and around the fan. The flame then spread downwind to ignite roadway timbers.

2). By tragic coincidence, forty-eight men riding through the return airway were overtaken by smoke containing carbon monoxide and forty-seven of these men were asphyxiated.

3). The fire would not have reached dipterous proportions had inflammable material been excluded from a substantial length of roadway immediately adjacent to and on the return side of the fan.

4). The haze which proceeded the smoke was not recognised, either by officials or by workmen, as a sign on imminent danger. By the time the fire was found the second men-riding train had already left the pit bottom.

5). Fire fighting arrangements were inadequate but the deficiencies did not contribute to the loss of life.

6). The fire would probably have been averted had the fan been under continuous supervision. It might have been averted or it’s development halted had the fan been inspected at half-hourly intervals prescribed as a maximum by Regulation.

7). Closer examination of the belt performance after speeding up the fan might have indicated the advisability of reverting to the previous speed or altering the drive.

8). The unsatisfactory performance of the belt and the damage done to it in the two days before the fire, particularly the night immediately before, received insufficient attention.

9). By calculation, a balata transmission belt made of 33.3 oz. cotton dick put on after the speed-up of the fan had an excess capacity of about 50 per cent and a 31 oz. belt caught fire about 25 per cent. But the first of these belts lasted less than two weeks and the other only two days.

10). The belt which caught fire was not the 33.3 oz. weight ordered by the National Coal Board and failed to satisfy completely some of the tests prescribed by the British Standard 2066.

The Inquiry made the following recommendations following the disaster-

1) Underground booster fans driven by inflammable belts should be constantly attended by competent and properly instructed persons.

2) The bearings of underground fans should be lubricated with grease or any suitable non-inflammable lubricant that may be developed.

3). All power transmission belts used at collieries should be made of fire-resistant material. Pending the introduction of fire-resistant flat belting, managers should make effective arrangements to ensure that any overheating or fire in machinery, driven by an inflammable belt, will be discovered and dealt with before serious danger can develop.

4). All managers should carry out thorough reviews of their fire fighting arrangements to ensure that sufficient appliances in proper working order will be available for prompt use in any place where fire may break out underground. These reviews should include consideration of telephone systems and means of warning men of fire.

5). All managers should have made thorough examinations made of the whole of their pits to identify any places on unusually high fire risk and determine what can be done to minimise the risk at each of these places and to deal with any fire which might occur.

6). The attention of all officials should be drawn specifically to their obligation under Regulation 11 (1) of the Coal and Other Mines (Fire and Rescue) Regulations, 1956, that men must be withdrawn as soon as there is any indication that fire has, or may have, broken out below ground.

7). The industry should reconsider its decision to discontinue the trials of self-rescuers.

8). There should be a suitably constituted standing committee of experts, representing all sides of the Industry and the Ministry of Power, charged with the task of keeping under close and constant review the prevention of explosions and fires in mines, with particular reference to the lessons of actual fires and explosion in this country and abroad, and of anticipating any possible ignition hazards arising or likely to arise from new developments in mining practice.

REFERENCES

The report of the causes and the circumstances attending the underground fire which occurred at the Auchengeich Colliery, Lanarkshire, on the 18th September 1959 by T.A. Rogers, C.B.E., H.M. Chief Inspector of Mines.

Colliery Guardian, 22nd December 1960, p.730, 29th December, p.755.

The Auchengeich Colliery Disaster. The Scottish Area of the National Union of Mineworkers.

Information supplied by Ian Winstanley and the Coal Mining History Resource Centre.

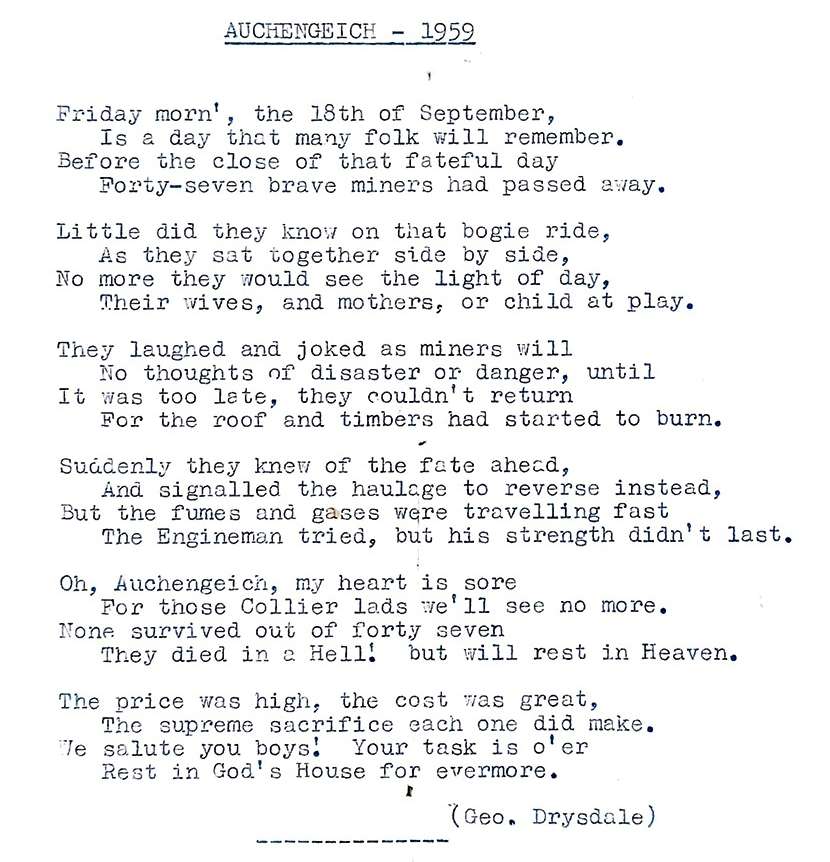

Auchengeich – 1959

Friday morn’, the 18th of September,

Is a day that many folk will remember,

Before the close of that fateful day

Forty-seven brave miners had passed away.

Little did they know on that bogie ride,

As they sat together side by side,

No more they would see the light of day,

Their wives, or mothers, or child at play.

They laughed and joked as miners will

No thoughts of disaster or danger, until

It was too late, they couldn’t return

For the roof and timbers had started to burn.

Suddenly they knew of the fate ahead,

And signalled the haulage to reverse instead,

But the fumes and gases were travelling fast

The engineman tried, but his strength didn’t last.

Oh, Auchengeich, my heart is sore

For those collier lads we’ll see no more.

None survived out of forty seven

They died in a hell! But will rest in Heaven.

The price was high, the cost was great,

The supreme sacrifice each one did make.

We salute you boys! Your task is o’er

Rest in God’s House for evermore.

(Geo. Drysdale)

Return to previous page