GREAT WESTERN. Rhondda, Glamorganshire. 11th. April, 1893.

The colliery was at Gyfeillon in the Rhondda Valley about two miles from Pontypridd in the heart of the South Wales Steam Coal Field. It was one of the largest collieries in the district and was owned by the Great Western Colliery Company, Limited with Messrs. Forster Brown and Rees, mining engineers of Cardiff as the consulting engineers for the company.

The managing staff consisted as Mr. Hugh Bramwell, agent, Mr. William James, certificated manager, Mr. David Rees, certificated undermanager, Mr. Evan S. Richards, holder of a First Class Certificate but acting as assistant manager. Mr. W.M. John was the surveyor and Mr. R.L. Molyneaux the mechanical engineer. There were also three overmen and seventeen firemen. Mr. Bramwell was a mining engineer and certificated manager and had succeeded Mr. H.T. Wales of the 1st. January.

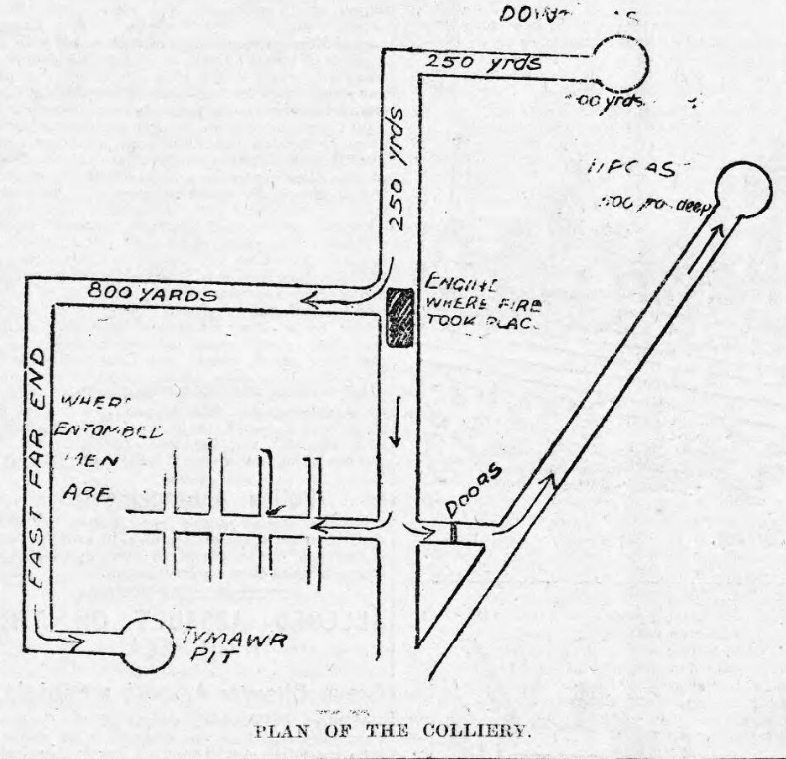

There were three shafts at the colliery. The Hetty was the downcast and was sunk to the Six Feet Seam and was 398 yards deep. The No.2 Pit was the upcast to the Five Feet Seam at a depth of about 472 yards and the Tymawr Pit was an upcast was also sunk to the Five Feet Seam at 472 yards. Coal was raised at all the shafts.

At the Hetty the Four Feet and Six feet Seams were worked. The Four Feet Seam lay 25 yards above the Six Feet and was passed through in the shaft but for greater safety and convenience in winding, all the coal was raised from the Six Feet Seam, the lowest landing in the shaft. At the No.2 Pit only the Five Feet Seam was worked and raised from the Five Feet landing. The Tymawr Pit the Five Feet Seam was being worked and raised for, the Five Feet landing.

The ventilation of the colliery was produced by two Schiele fans each of fifteen feet three inches diameter. One was placed at the top of the No.2 Pit which was elliptical in section measuring 14 feet 4 inches and 10 feet 9 inches. the other was placed near the top of the Tymawr Pit which was also an elliptical shaft 16 feet by 10 feet. The downcast shaft, the Hetty Pit, was circular and 16 feet in diameter. About 270,000 cubic feet of air per minute circulated through the workings which were recognised as amongst the fiery in the South Wales District.

The whole of the colliery was equipped with modern machinery and appliances geared to a large output of steam coal and both the Hetty and the No. Pits had been safely worked since 1877 when the shafts were first sunk to the steam coal measures. Before this house coal had been worked. The Tymawr Pit had only been recently acquired by the Company and sunk by them to the lower steam coals. Previous to this the east workings in the Four Feet from the Hetty Pit had been extended beyond the Tymawr Pit and since the latter was the upcast shaft, it was more convenient to connect these workings to it for the purposes of ventilation, so that the large district of the Four Feet Seam at the Hetty Pit had a direct connection with the Tymawr upcast in that seam. The explosion affected the workings in the Four Feet Seam to the east of the Hetty Pit and their connections with the landing in the Six Feet Seam.

The total number of men working in the three pits was about 1,460 of whom 950 were at work on the day shift on the day of the accident. Of this number 212 were in the east workings of the Four Feet Seam all of which were put in danger from the resulting fire. Of the 212 persons, 78 were in the East main Dip and 134 in the East Main Level. Those in other parts of the mine, although never in danger from the fire, were all quickly withdrawn and sent to the surface.

Haulage by machinery was largely used and in common with many of the larger collieries, compressed air was used for the transmission of power for the underground machinery from the compressing plant at the surface. There were 15 haulage engines in the whole of the seams and it was at one of these engines that the disastrous fire originated.

On the East Level in the Six Feet workings, about 120 yards from the Hetty Pit, a main road, the “East Hard Heading”, branched off at right angles and this road rising 1 in 6, cut the Four Feet at 156 yards. It was here where the engine in question was situated. From this point, the East Main Dip continued in a straight line for 270 yards and then turned to the right where it was called Sam Cull’s Dip and continued a further 400 yards. At 176 yards down Sam Cull’s Dip, a pair of headings branched off at right angles to the right and 160 yards further down two headings branched off to the left. The headings to the right extended 396 yards to the rise and those to the left 114 yards to the dip. These headings and the 29 stalls at work in them formed one ventilating district, which was termed the East Main Dip and which was ventilated from the No.2 upcast shaft.

From the top of the Easy Hard Heading just inside the engine, another road called the “Four Feet East Level” branched off to the right for a distance of 463 yards to the top of “Thompson’s Dip”. Witt’s Level was reached from Thompson’s Dip by branching off to the right and this extended 548 yards to the working headings to the rise. Thompson’s Dip continued in a straight line for a further 363 yards. On the east side there was a level 143 yards long to the working heading and on the west side another level which reached the last of the three headings for 288 yards.

The three divisions formed one large district ventilated to the Tymawr upcast shaft. These roadways were the haulage roads and the intake airways and all had a minimum square section of 50 square feet and beyond the engine for a few yards where it was split. About 72,000 cubic feet of air per minute passed up the East Hard Heading. About 57,000 cubic feet went to the East level and 15,000 to the East Main Dip, passing the engine at about 20 feet per second.

The mine was very dry and there were provisions for damping the roadways and a system of spray jets which were fixed at intervals of about 40 yards in the principle intakes. The water came from the surface by pipes some two and someone and a quarter inches in diameter, down the shaft and along the haulage roads. There were 5 miles of piping laid for this purpose.

The engine was fixed immediately over the roadway on pitch pine beams resting on the sidewalls of masonry. the engine had two cylinders with a twelve-inch stroke which worked two loose drums by spur gearing, geared 4 to 1. The drums were three and a half feet in diameter and each had a brake fitted consisting of an iron strap to which were bolted elm curb blocks. The brake extended for half the circumference on the drum and was four inches wide. The brake leverage on the drum working the main rope was 15 to 1 and that of that working the tail rope was 45 to 1. The engine worked the haulage on the East Hard Heading, the East Main Dip and the East Level as far as the top of Thompson’s Dip.

Six trams at a time were hauled up the East Main Dip by the main rope drum and lowered down the East Hard Heading by the tail rope drum. Twelve trams at a time were hauled along the East Main Level by the main rope and lowered down the East Hard Heading by the tail rope drum. While a journey was being hauled from the East Level, the tail rope was attached behind and drawn out, so that the next empty journey could be hauled in by this rope. The rope passed round a sheaf at the inner end of the East Level. When a journey of twelve trams weighing 19.2 tons, was being lowered by the tail rope drum down the Hard Heading there would have been a strain of 3.2 tons on the drum and the breaking would have been very severe.

The woodwork holding the engine consisted of two wooden cross beams 12 inches square and, 13 feet long, one cross beam 12 by 10 inches and 13 feet long, one cross beam 8 inches square and 10.5 feet long, two longitudinal beams 14.5 by 8 inches and 16 feet long, a platform of one and half inch deal, 10 feet by 4 feet and the blocks that formed the brakes. The engine was in the main intake and the engineman had placed a canvas brattice cloth at the ends and below the drums to give shelter from the strong air current and the dust that was blown off the passing trams. Except for a small quantity of cylinder oil, olive oil for the bearings and some cotton waste for cleaning the engine, there was no inflammable material about other than the woodwork and the canvas. There would have been a considerable amount of oily and greasy material on the woodwork below the drums. The place was lit by an electric lamp which was the last of a series from the shaft bottom.

Fire had not been anticipated here and there was no provision to deal with it. There was an upright water pipe which supplied water to spray jets which had a few feet of hose attached. The pipe had a tap so that water was readily available. One bucket was kept near the engine. The engineman who normally worked the engine had been absent for some days owing to ill health. This man appeared to have been in the habit of keeping the bucket full of water and occasionally using the water to cool the brake blocks. The engineman on duty at the time of the accident did not provide himself with any water.

The fire appeared to have been discovered by a boy, Edwin Matthews, who went down the Hetty Pit at about 1.30 p.m. to work with a collier on the afternoon shift in the Four Feet seam, When he was passing up the East Hard Heading, he noticed something on fire below the engine, called to the engineman and ran back towards the Hetty Pit. A journey of trams was being hauled up the East Main Dip and George James, the engineman, stopped the engine, came down the roadway and saw one of the beams on the fire. He and the rider of the journey, John H. Thomas, who had run out to see what the matter was, tried to put out the fire by beating it but they failed to do so. They then tried to get water from the tap but there was no water in the pipe. In a few minutes, they were joined by some men who came from the shaft and directly afterwards by David Reeds, the undermanager who happened to be near the Hetty Pit bottom when the alarm was raised. The pipe carrying water to the spray had been broken by the engineman top try to get some water but the pipe was empty. Some of the men were carrying buckets from the cistern in the stables in the Six Feet Level at the bottom of the East Heading. The fire was now being spread inwards and caught the timbers supporting the roadway at the top of the East Main Dip and the entrance to the Four Feet East Level

The first intimation that there was something wrong reached the Tymawr Pit a little before 2 p.m. when John Cannon, the hitcher in the Five Feet Seam, heard someone crying from the Four Feet Seam above, “Let’s have the carriage, quick.” He went up with the next cage and sent three cage loads of men to the surface. He went up with the fourth cage load. Three or four more cage loads were raised from the Four Feet and the last one brought up one man, William Fletcher. While these men were being raised, one man, Jesse Titley, probably owing to his exhausted condition, or the difficulty of seeing the cage in the smoke, fell down the shaft and was killed.

Four other men had managed to reach the landing at Tymawr Shaft but were too exhausted to get through the wooden fence protecting the entrance. Several attempts were made by some of those who escaped and others but the state of the atmosphere was such that they could not be rescued alive.

The speed of the ventilation fan at the Tymawr Pit had unfortunately been increased soon after it became known at the surface that something was wrong. This was done in the excitement of the moment and in the belief that an explosion had occurred. The greater quantity of air fanned the flames and carried the smoke more quickly into the Four Feet East workings. Mr. James, the manager, arrived at the scene of the fire and soon decided that the proper course was to reduce the speed of the fan. He was of the state of affairs at the Four Foot Landing in the Tymawr Pit and he thought that all the men in East District had been able to reach the landing, he sanctioned the stopping of the fan there and the lifting of the top covers off the pit wit the object of turning the shaft into a downcast and getting fresh air to the landing to help with the rescue of the men who were there.

The fan was stopped between 3.15 and 4 p.m. and during this time the bodies of four men who had died at the landing were brought up but no more came out alive by that road nor cold any sign of life be seen for about 100 yards inwards which was the distance which Mr. Jones, the surveyor was able to explosion. the fan was the run at half speed.

The manager then attempted to reach the East Main Dip working by way of the return airway, this proved impossible due to thick smoke. About 4.15 p.m. Mr. Bramwell arrived and descended the pit and joined Mr. James, the manager. Soon after steps were taken to increase the supply of water from the shaft to the fire and supplement the supply of water from the stables and the sump which was being used to fight the fire.

On the day of the accident Mr. Robson, the Inspector was at a colliery near Merthyr and went to the Great Western Colliery when he returned home at 9 p.m. and heard that he was required. Mr. J. Mancel Sims, the assistant Inspector arrived at the colliery at 8.45 p.m. and another Assistant Inspector, Mr. J.D. Lewis arrived at 12 p.m. both Mr. Sims and Mr. Lewis went underground and remained at the colliery until Mr. Robson arrived at 10.45 a.m. the following day.

Fortunately, the brick arch which formed the air crossing over the Main East Dip, 15 yards beyond the engine helped to stop the spread of the fire down this road and about 6 p.m. the fire had been sufficiently subdued to allow an attempt to reach the workings of the East Main Dip. William Prosser, a fireman and the brother of a fireman in this district, got down as far as the first door, 210 yards down. They opened the door to help the smoke clear away from the dip and stop it from going into the working headings. His light went out and he returned to the engine. Getting another lamp and this time accompanied by Morgan Thomas, overman and Lewis James, fireman, he again went down the dip passing the second door near the top of Sam Cull’s Dip and the third door beyond the first working in the heading. Both doors were found to be open and they reached 78 men including Thomas Rosser, all were gathered together and uninjured about 100 yards up Holbrook’s Heading. They all walked out by the intake and reached the surface at about 6.30 a.m.

Mr. Robson commented in his report:

Great credit is due to Thomas Rosser, the fireman for this district, for his coolness and prompt action on discovering that smoke was entering the workings by the intake. It appears that he smelt smoke about 1.45 p.m. while standing near the double parting on Holbrook’s heading, and at once went down the dip, meeting David Richards, master haulier, who told him that there was a lot of smoke coming down the dip behind him. Thomas Rosser immediately sent some men into the working places with instructions to withdraw all men and boys and bring them to the double parting. Rosser, Richards and another man, William Deveraux, went up the dip, through the smoke, and realising the gravity of the situation, made an effort to reach the outermost of the two doors with the intention of opening it and so short-circuiting the air current. They, however, failed in this, and returning, opened the second door near the top of Sam Culls dip, and then reached the double parting again where the men were beginning to gather. Although most of the men reached, most of the men wanted to make an attempt to get out by the main intake; Rosser was able to dissuade them from this course.

Bye and bye the atmosphere, notwithstanding the opening of the door above mentioned, became by diffusion so impregnated with smoke that he had to move the men further up the heading. He then opened a door between Holbrook’s and Ostler’s Headings and afterwards another on the first crossing 73 yards up these headings, finally erecting a brattice across Holbrook’s Heading inside of this crossing and retreating with the men to the inbye side of it. They waited there about 280 yards from the face of Holbrook’s Heading. Gas had by this time accumulated in the heading and stalls and before they left Rosser had ascertained that it showed in the lamp 120 yards from the face.

In the meantime, some unsuccessful attempts had been made by those on the surface to enter the Four Feet Seam by the Tymawr return but it was not until 8 a.m. on Wednesday when Mr. Bramwell, Mr. William Stewart of Harris’ Navigation, and Ivor John, a fireman, made the attempt, that this was accomplished. They reached by way of Bidman’s Old Dip and Osbourne’s Cross Heading, James Holbrook’s Level, where they found the body of a haulier and two horses, but the air was too heavily charged with smoke to remain many minutes and they returned to the surface. Mr. Stewart was affected by the smoke but recovered in a day or two.

Efforts were made to overcome the fire in the Four Feet East Level were continued during the night and the following day but the work of getting the water to the fire became more and more difficult owing to falls of roof and the smoke and steam of the burning mass behind which was more or less buried by falls. By midday, on Wednesday it was possible to reach the engine about 70 yards outside Thompson’s Dip, and the body of the engineman was seen in the engine house.

The condition of the air in this level, however, was such that no one could remain in it for long, and it was deemed unwise to make any more attempts until the fire had been reduced and the roadway cooled. Compressed air pipes had been considered by the management and Mr. Treherne Rees, one of the consulting engineers, but the water pipes would not take the pressure. This plan was eventually carried out with the precaution of tapping the column about 70 yards from the bottom of the shaft to relieve the pressure. The work was completed by 11 p.m. on Wednesday and the extra water delivered by these pipes was delivered and enabled the falls to be cooled down sufficiently for the east district and Thompson’s Dip to be explored. This work was completed by 2 a.m. on Thursday but no signs of life were discovered.

Those who died were:

- Lewis Thomas aged 25 years, haulier.

- William Thomas Cole or Vole, aged 16 years, collier.

- Richard Edmunds aged 25 years, collier.

- Morris Potter aged 28 years, collier.

- George C. Lewis aged 15 years, collier.

- William James Bond aged 16 years, collier.

- George Bartlett aged 23 years, collier.

- William Bowers aged 22 years, collier.

- Ivor Lloyd aged 22 years, collier.

- Gwilym Howells aged 17 years, collier.

- John Williams aged 31 years, collier.

- William C. Balling aged 21 years, collier.

- John Thomas aged 27 years, collier.

- Daniel David aged 17 years, collier.

- William Thomas aged 18 years, collier.

- John Roberts aged 21 years, collier.

- Albert Pearce aged 16 years, collier.

- William John aged 42 years, collier.

- David Jenkins aged 31 years, collier.

- Ernest Thomas Prosser aged 18 years, collier.

- Thomas Henry Williams aged 17 years, collier.

- Coleman Williams aged 17 years, haulier.

- Morgan Williams aged 57 years, collier.

- John Williams aged 61 years, labourer.

- Joseph Williams aged 37 years, collier.

- Arthur Thorne aged 16 years, collier.

- William Edmunds aged 52 years, roadman.

- William Lewis aged 44 years, collier.

- Amazia Jones aged 15 years, collier.

- Arthur Davies aged 33 years, collier.

- Job Miller aged 18 years, collier.

- Daniel O’Shea aged 16 years, collier.

- Adolphus Dodge aged 14 years, doorboy.

- James Holbrook aged 25 years, collier.

- David John aged 17 years, collier.

- Lewis Jacob aged 20 years, collier.

- David W. Prosser aged 17 years, collier.

- John Llewelyn aged 45 years, collier.

- Frederick Nurse aged 16 years, collier.

- George Thorne aged 31 years, collier.

- William Wheeler aged 16 years, collier.

- Jesse Titley aged 19 years, collier.

- Lewis Williams aged 26 years, collier.

- William Williams aged 20 years, collier.

- Charles Caville* aged 50 years, collier.

- Phillip Jones aged 42 years, collier.

- Cornelius Hayes aged 18 years, oiler.

- Thomas Lambert aged 27 years, rider.

- Daniel Spooner aged 35 years, haulier.

- John Nichols aged 26 years, engineman.

- Frank Grainger aged 28 years, inclineman.

- Thomas Price aged 15 years, doorboy.

- George Roderick aged 14 years, collier.

- David John Powell aged 13 years, collier.

- Charles Godfrey aged 28 years, collier.

- William Davies aged 17 years, collier.

- John Maddox aged 33 years, collier.

- William Hughes aged 17 years, collier.

- Thomas Davies aged 29 years, bratticeman.

- David Davies aged 29 years, fireman.

- Mark Osborne aged 26 years, collier.

- James Devereux aged 39 years, lampman.

- Patsey Sullivan, rider

Of the 134 men and boys in the East Level district, 37 out of 52 in the East far end 14 out of the 23 in the East side of Thompson’s Dip, 19 out of 48 in the West side of Thompson’s Dip and 1 out of 11 on the roads inbye of the engine were saved.

The inquest into the disaster was held before Mr. .B. Reece, Coroner for Cardiff and Mr. R.J. Rhys, Coroner for Aberdare and a jury at the New Inn, Pontypridd from the 27th to the 29th April. All interested parties were represented and the jury returned the following verdict:

We find that the accident the Great Western Colliery on 11th April 1893 caused by a spark or sparks emitted from the brake of the hauling engine at the hard heading, which came in contact with some inflammable substance in the neighbourhood and we do not attribute any negligence to any of the officials either before or after the accident, and that 61 men lost their lives by suffocation from smoke arising from the fire and that Jesse Titley lost his life by falling from the 4-foot landing to the bottom of the seam at Tymawr Shaft.

The jury also recommended:

1) That the code of regulations drawn up by Hugh Bramwell be sent to the Home Secretary wit the object that those or similar ones should be adopted in other collieries.

2) That sufficient width or surface for brake power be provided at all haulage engine, so as to prevent undue friction.

3) That every care should be exercised in letting down full journeys upon the east hard heading at the Great Western Collier at a uniform rate and speed.

Mr. Robson concluded his report by saying that the loss of life would have been much greater it the Tymawr upcast shaft had not been a winding pit.

REFERENCES

The Mines Inspectors’s Report, 1893. Mr. Robson.

“And they worked us to death” Vol.2. Ben Fieldhouse and Jackie Dunn. Gwent Family History Society.

Information supplied by Ian Winstanley and the Coal Mining History Resource Centre.

*Supplied by a researcher – the original name was Coville

Return to previous page