KNOCKSHINNOCK CASTLE. New Cumnock, Ayrshire. 7th. September, 1950.

Knockshinnock Castle Colliery was situated in the Parish of New Cumnock in Ayrshire about 22 miles due east of the town of Ayr. Before the accident the colliery employed about 600 men underground and 120 at the surface with a weekly output varying from 4,500 to 5,000 tons. The output came from two seams, the Main Coal and the Turf Coal with the major proportion coming from the Main Coal. The downcast shaft was completed in 1942 and was used for the winding men, materials and mineral and was 16 feet in diameter sunk to 122 fathoms. The older Knockshinnock No.1 pit served as the upcast shaft and as the second exit which only about a quarter of a mile to the north of the downcast shaft and was 12 feet in diameter and 70 fathoms deep.

The ventilation was produced by an Aeroto fan which was at the surface of the No.1 pit and passed 65,000 cubic feet of air per minute at a water gauge of 4.5 inches. Safety lamps were used throughout the mine and the type provided for the workmen underground were the Oldham, Wheat Q Type, 4-volt electric cap lamp. For gas testing, the workmen were issued with Prestwich Patent Protector, Type SL, magnetically locked flame safety lamps and the officials with the Prestwich Patent Protector, Type No.6 flame safety lamp fitted with internal re-lighters and magnetically locked. Limestone dust was used for stone dusting throughout the colliery. At Knockshinnock Castle downcast shaft an underground pump wit the capacity of 500 gallons per minute which ran for three hours a day and a second with a capacity of 125 gallons per minute which ran for 12 hours a day.

The colliery was operated by the National Coal Board, Scottish Division and was one of fifty producing collieries, many relatively small which were in the Ayr and Dumfries Area. The Area was divided into three Sub-Areas, each of which were divided into Groups. Knockshinnock Castle was the largest of the six collieries in the New Cumnock Group in the Dunaskin Sub-Area which had 21 collieries in it. The manager of the colliery was Mr. W.C. Halliday who was assisted by an Undermanager, Mr. B.Y. Kennedy. There was an overman, Mr. J.N. Houston who was in general charge underground of the day shift and he was followed by a second overman, Mr. Andrew Houston, who was in charge underground on the afternoon shift. There was no overman on the night shift. Five firemen were in charge of the working districts on each of the three shifts; Mr. J. Bone was the Agent for the New Cumnock Group. The Dunaskin Sub-Area was under the general charge of Mr. A.M. Smart, the Sub-Area Production Manager who was in turn responsible to Mr. A.B. Macdonald, the Area Production Manager. Mr. D.L. McCardel was the Area General Manager. All these higher officials held a first-class Certificate of Competency.

The Sub-Area had a Planning Department and a Surveying Department. The Planning Department employed planning engineers and planners. The Sub-Area Planning Engineer was Mr. Alex Gardner who held a first-class Certificate of Competency and Mine Surveyor’s Certificate. His assistant was Mr. Donald Mackinnon who possessed a first-class certificate. The Sub-Area Senior Planner was Mr. J.H. Cairns who controlled activities of four Assistant Planners, one for each of the Agent’s Group of collieries in the Sub-Area. The Assistant Planner concerned with the Knockshinnock Castle Colliery was Mr. R. McLean who held a Mine Surveyor’s Certificate. The Sub-Area Chief Surveyor was Mr. C. Stewart and his senior assistant was Mr. T.D. Brown. The surveyor attached to the New Cumnock Group was Mr. R. Arbuckle who was assisted by an apprentice surveyor, Mr. Ian Murray.

This portion of the Ayrshire coalfield in the New Cumnock district lay at the extreme southern edge of the coal measures and was bounded on the south by a large upthrow fault, the Southern Uplands Fault. The coalfields was unique among the coalfields of Britain in that the workable seams that are found in four groups of the carboniferous rocks, the Barren Red Measures, True Coal Measures, Millstone Grit Series and the Limestone Series. There were twenty-eight coal seams which were greater than two feet thick which had been proved and of there seventeen are over three feet thick and nine exceeded four feet. These seams were unknown in the Knockshinnock Castle Colliery Area until a few years before the disaster and the existence of the Main Coal was only finally proved in 1938.

Apart from the Southern Uplands Fault, the New Cumnock coalfield was very faulted which resulted in the field being broken up into areas that were more or less detached and in some of these area coal had been worked for many years. One of the seams that had been worked over the years was locally known as the “Eight Feet”. In an older colliery near the Knockshinnock Castle Colliery a thick seam had been worked for many years and it was believed to be the Eight Feet. About 19320 the Geological Survey suggested that this was not the Eight Feet but was an entirely new seam and the geological position of this seam was about 100 fathoms below the Eight Feet in the True Coal Measures. To test this theory a borehole was put down in 1924 but the recorded results were disappointing and did nothing to alter local opinion. Some years later the views of the Geological Survey were reconsidered and it was decided that further boring was justified. A borehole was put down in 1938 and gave excellent results. It proved the existence of the Main Coal at the approximate position previously indicated by the geologists of the Survey as well as that of three other workable seams. Further boring confirmed the existence of these seams over several square miles which added many millions of tons to the reserves of the area. This valuable extension to the coalfield led very soon to the planning of the Knockshinnock Castle Colliery and the sinking of the downcast shaft began in 1940 and was completed in 1942.

Because of the inclination of the seams and the decision of the previous owners, the New Cumnock Collieries Limited, to use locomotive haulage in the main roads leading to the bottom of the pit, the shaft was not sunk to a particular seam but to a suitable horizon from which almost level mines or stone drifts were driven as main haulage roads to give access to the seams that were to be worked, especially the Main Coal. In common with the coalfield as a whole, the area of coal to be worked by the colliery was heavily faulted and due to these disturbances, the gradients of the seams varied from comparatively level to 1 in 2 and in parts even steeper. In addition, the composition and thickness of the seams were subject to variation. This was particularly true in the Main Coal which was approximately eight feet thick in which there were three distinct coal beds which were separated by dirt bands and with either a strong sandstone or a relatively weak “calmstone” forming the roof. Where the sandstone formed the roof, the full thickness of the seam was extracted and where the roof was calmstone the top leaf of the coal was left. The seams were naturally damp and it was not uncommon for the working places to be wet.

In the district where the disaster occurred, the No.5 Heading Section in the South Boig Area, the composition of the Main Coal remained reasonable constant and the coal lay in three beds which were known locally as the “head coal”, the “breast coal” and the “bottom coal”, separated by dirt bands with a calmstone roof above the head coal. Above the calmstone here was another thin bed of coal known as the Pennyvenie Seam which was overlain by a bed of sandstone. The method of working was Stoop and Room, the rooms being driven 16 feet to 18 feet wide to form stoops approximately 100 feet square. The direction of advance of the No.5 Heading Section was to the south-east towards the Southern Uplands Fault with the gradient steepening from 1 in 14 to 1 in 2 in the No.5 Heading which was the main haulage road for the district and was the leading place. Because the calmstone was weak and difficult to support the head coal was left to form the roof and only the breast coal and the bottom coal were extracted with the associated dirt bands which gave a working height of about 7 feet.

The coal was blown from the solid by explosives and the shotholes were bored by electrical machines with approximately 18 holes being bored for each round of shots. The faces advanced about 9 feet per shift and two shifts of coal getters were employed. The coal was hand loaded on to scraper conveyors which delivered to a series of belt conveyors, two in the No.5 Heading and one in the Belt Conveyor Heading. At a central loading point at the junction of this heading with the South Boig Mine, the coal was delivered into tubs which were hauled to the pit bottom by locomotives by way of the South Boig and the West Mines, both of which had a gradient dipping slightly towards the shaft. In the headings going steeply to the rise, the No.5 Heading, a short shaker conveyor was used next to the face. For several days before the accident this heading had been stopped and the shaker conveyor partly dismantled.

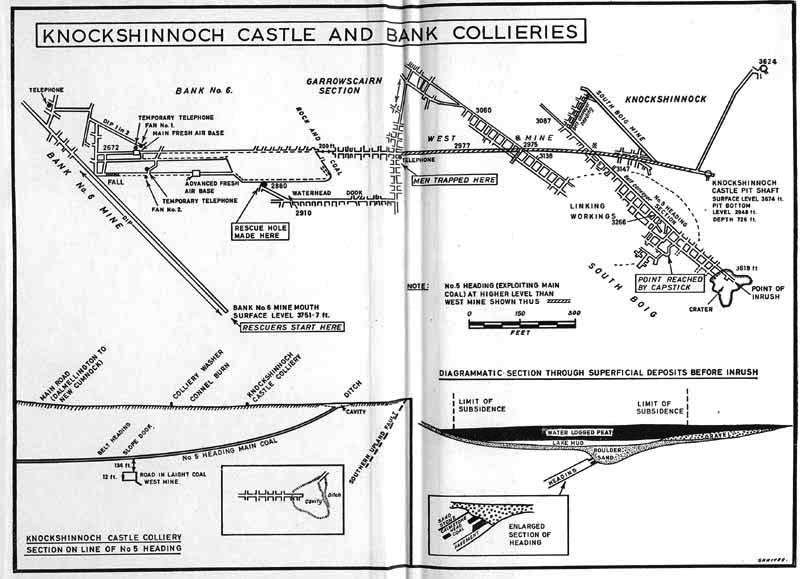

At the neighbouring Bank No.6 Colliery, the Main Coal was reached by a dipping drift driven from the surface, mostly in stone but partly n coal, with a gradient varying up to 1 in 3.6. The mouth of the drift lay approximately a mile to the south-west of the Knockshinnock Castle Colliery. About 1944 a district in Bank No.6, known as the Waterhead Section, was worked to the rise by a longwall face. Later the Main Coal in Knockshinnock Castle was also worked in the Waterhead Area towards Bank No.6 leaving a barrier of coal 200 feet wide between the two collieries. In order to facilitate drainage from the Knockshinnock side, a roadway was driven into this barrier up to a point about 24 feet from the Bank No.6 workings. A borehole was then put through the remaining part of the barrier to carry the water. it was through this part of the mine that the escape road was driven, by which 116 men imprisoned by the disaster were eventually rescued.

Deposits of peat moss occurred on the surface in the immediate neighbourhood of both the collieries and were shown on the 6-inch Geological Survey Map of Ayrshire, Sheet XLII S.W. One such deposit was shown, part of which actually covered the place where the disaster originated. There was no previous history of an inrush of moss in the area but a few years before work had been carried on underground in Bank No.6 Colliery when Mr. J. Bone was the Agent, when a surface peat deposit had to be probed to determine its thickness in order to comply with the General Regulations of 1920, relating to precautions to be taken when working under a peat moss.

The accident occurred at about 7.30 p.m. while the afternoon shift was at work on Thursday 7th September 1950 when a large volume of liquid peat or moss suddenly broke into the workings from the surface in the No.5 Heading Section of the Main Coal Seam. The inrush started at the point where the No.5 Heading, which rose at a gradient of 1 in 2, had effected a holing at the outcrop of the seam beneath superficial deposits and had made contact with the base of a relatively large natural basin containing glacial material and peat. The liquid matter, rushed down the steep heading and continued to flow for some time and soon filled up a large number of existing and abandoned roadways as well as several working places, until it eventually cut off two means of egress to the surface from the underground workings of the colliery.

There were 135 people underground at the time. Six working near the shaft bottom escaped to the surface by the downcast shaft before it became blocked while 116, with all means of escape cut off, fond their way inbye to a part of the mine which was the unaffected by the inrush leaving 13 men who were missing. The 116 men were rescued about two days later and the 13 missing men, all of whom were employed in the No.5 Heading. One was the fireman in charge of the district, one shotfirer and nine coal getters who were employed at the face and three working in other places. There were also two men who were working on the haulage of the district.

The No.5 Heading Section had been developed to exploit the area of Main Coal which lay to the south of the shafts and a pair of headings at 100 feet centres was driven into the coal at a rise in a south easterly direction. These headings were about 18 feet wide and 7 feet high. Connections were put through between the headings to form stoops about 100 feet square. One of these headings was known as No.5 Heading. It was used as the main haulage and travelling road for the Section and was always kept in advance of its companion heading.

A contoured development plan had been sent to the Manager by the Sub-Area Planning Department in April 1950 and this indicated in blue, the extent of the expected progress of the workings until 1st. September 1950 and in orange the progress expected from then until the 1st. February 1951. It was nothing more than a progress plan based on the already established Stoop and Room system of the working but it did not show that the main development Headings would reach the conjectural position of the Southern Uplands Fault and that at that stage it would have at least 100 feet of cover from the surface. These conjectural plans were based that the unworked coal ahead rose at a gradient of 1 in 4. After that time, as might have been anticipated in a seam rising towards a major upthrow fault the gradient became steeper and on the 6th. July 1950, when the last quarterly survey was made before the inrush, levellings showed that the face of the No. 5 Heading was only 196 feet vertically below the surface, By this time it had become obvious to the management that the main headings would not strike the Southern Uplands Fault because of the gradient of the seam, which had been increasing for some time, continued to steepen until it became almost 1 in 2 and that the headings would reach the outcrop of the seam near the surface at a point somewhere south of the shafts. The report commented:

This fact does not appear to have been treated by the management as a matter of concern nor as something to which the attention of the planning department should have been drawn.

For at least a year before the inrush it had been realised by the management that if certain inbye districts of the colliery were to be fully exploited and adequately ventilated, it would be necessary to increase the quantity of the air circulating underground. Eventually, in order to achieve this, it was decided to drive a new dipping drift starting from the surface to meet the underground workings and thus provide an additional airway. This drift was in the course of being driven at the date of the disaster. When this drift was commenced, no one knew that the development headings in the No.5 Heading Section were likely to reach the surface. But as soon as the management realised that the headings, if continued, were bound to reach the surface, the prospect of being able to drive a road in the coal to the surface seemed to have appealed to them. At any rate, during the year the matter was discussed by the undermanager, manager and agent but strangely enough no decision was taken about it. At the inquiry, the undermanger believed that it was the intention was to drive No.5 Heading through to the surface to provide a new airway but the manager said that the idea was considered by the agent and rejected. The agent said that the matter was still under consideration a few days before the disaster. The report commented:

Altogether, the evidence on this important matter of planning was unsatisfactory, conflicting and disappointing.

Whatever was said, the No.5 Heading and the companion heading were driven rapidly forward. Nothing untoward happened until about 10 a.m. on the day shift of Wednesday 30th. August when a shot was fired in the breast coal at the face of the No.5 Heading by the fireman, D. Strachan who was one of the victims of the disaster. this shot blew through and exposed what appeared to be a bed of stones, leaving an opening described as two to two and a half feet wide for the full height of the breast coal and four to five feet deep. Water started immediately to run out of this opening but, of the many witnesses that saw none could estimate the flow with any degree of accuracy. It was best described by one of them as the amount that would flow from a two-inch pipe. The water was clear and fresh and had no smell and it was allowed to flow freely down the floor of the heading. The flow of water remained fairly constant until the morning of the accident and did not appear to have caused much alarm to anyone, certainly not any of the officials in the colliery from overmen upwards.

When the holing was effected the place was stopped and no more coal was won from it. The dayshift overman, J.N. Houston, who was on duty in the section at the time, saw the hole about 15 minutes after the shot had been fired. Several other shotholes had been bored in the coal at the face of the heading but none of these had been fired. Water came from one or more of them but there was disagreement on the number by the witnesses at the Inquiry. The manager inspected the place about an hour later and very wisely decided that wooded chocks or pillars should be built to support the roof to supplement the props and bars ordinarily used to support the roof, to make the place more secure. Eight chocks were built in the following week.

Mr. Kennedy the undermanger, visited the face of the heading about noon on the day following the holing but Andrew Houston, the overmen in charge of the back shift did not inspect the face after the shot had blown through. He had been made aware of the position by the day shift overman who informed him that the heading had holed through “on the crop” had been stopped. Mr. J. Bone, the Agent, was also told that the heading had reached the outcrop but he did not visit the place.

On Thursday 31st August, as soon as the No.5 Heading had holed through, the Agent gave instructions for the underground workings to be surveyed and levelled by Mr. Ian Murray, an apprentice surveyor, to determine the exact position of the face of the No.5 Heading and its depth below the surface. The survey showed that there was about 38 feet of cover between the roof of the heading and the surface. On the same day a survey was made on the surface by Mr. T.D. Brown, the senior assistant surveyor for the Sanquhar and New Cumnock Colliery Groups. During the course of the survey, a pointed wooden peg, two feet long and two inches square, was knocked into the ground to mark the point immediately above the face of the No.5 Heading. This peg was knocked in by Murray who used a 2lb. hand hammer and the peg went in more easily than he expected for per of its size. He was not curious and did not think any more about it but he did notice that the ground underfoot was a “wee bit soggy” Mr. T. Brown, who had walked over the ground while he was taking his measurements described it as ordinary soil. To him it was green pasture with grass on it.

About that time, Mr. Halliday, the manager and Mr. Bone the agent together with Mr. D. Mackinnon, the Sub-Area Planning Engineer, also walked over the ground to see where the No.5 Heading would come out if it were driven right through to the surface. The report commented:

Surprising as it might seem, although Mr. Bone and Mr. Mackinnon had previous experience of workings under moss at other collieries, neither of them noticed the presence of peat or moss or anything unusual in the character of the ground, or even any feature to arouse any suspicion of danger.

As the development headings had been stopped, the miners who had been working in them had been transferred outbye to new places on the left of the dip side of the No.5 Heading, one place being six and the other seven stoop lengths back from the face of the heading. The other set of miners was put to work in a place going to the right or rise side of the companion heading, six stoop lengths back from the face of the heading.

The flow of water through the hole in the No.5 Heading remained fairly constant until the morning of the 7th September, the day of the disaster, when a marked increase in the flow was noticed. It was described as two or three time the flow that had been previously noted. About 9.30 a.m. the day shift fireman, Thomas McDonald, informed the day shift overman, J.N. Houston about the increase on the flow of water. The overman went to the face of the heading and found that the hole in the coal was a little wider but the stones at the back appeared to be in the same state as when the shot was fired. As the water was finding its way into the outbye working places on the dip side of the No.5 Heading the overman gave instructions to one of the oncost men to dig gutter to confine the water to the heading. The undermanager arrived shortly afterwards but, as he had hurt his knee, he did not go right up to the face but stopped 100 feet short. He discussed the position with the overman but they seemed to have been more concerned as to whether the outbye pumps would be able to deal with the increase of water than with any danger that might lurk there.

The increased flow of water carried a lot of loose coal down the heading and an occasional stone or pebble. This caused problems with the conveyor belts with the result that very little actual work was done on that morning. When the overman came to the surface at 3.30 p.m., he informed M.r Kennedy, the undermanager, that the flow of water had not increased since 9.30 a.m. Mr. Bone, The Agent and Mr. Arbuckle, the surveyor were present. He told then that the fireman had reported that two chock pillars had fallen out before the end of the shift. It appeared that the base of the chocks had been levelled on loose dirt and the water had washed this away, loosening the pillars.

On the afternoon shift of the 7th, three sets of miners were sent to work in the places already described, off the No. 5 Heading. The men working in the right-hand place were J.D. Houston, T. Houston, and W. McFarlane. In the outbye dip-side place were J. Smith, S. Rowan and W. Lee and in the place a stoop length above were J. Love, J. Murray and J. White. About 6.30 p.m. the No.5 Heading Section fireman, Daniel Strachan, sent a message saying he wished to see the overman, Andrew Houston. Houston sent word to the fireman to come out and he met him 50 yards inbye from the pit bottom. Strachan said that there had been a big fall at the face of the No.5 Heading and that it extended to a point roughly 300 feet from the return end of the conveyor and that the water had practically stopped running. Houston instructed him to go back and satisfy himself as to the condition of the Section while he went back to have a look at the surface.

Houston went to the surface and found a hole in the ground 25 to 30 feet long and 10 to 15 feet broad and 2 feet deep. About 6.40 p.m., he telephoned the manager and told him about the fall and the hole on the surface. The manager gave instructions for a fence to be erected around the hole as a right of way existed across the field and as there were not sufficient men at the surface, he told Houston to bring three men out of the pit. The manager had been absent on leave earlier in the day but when he got Houston’s message, he came to the pit to see things for himself.

Houston them went underground to look at the position in the No. 5 Heading. he went along the South Boig Mine and met John Dalziel at his working place at the foot of the Belt Conveyor Heading and at its junction with the No.5 Heading he met William Howatt, switch attendant. Houston continued up the No.5 Heading and as he reached a point just inside the return airway he felt a sudden blast of air which came down the heading. He went on inbye and met J. Montgomery, another belt attendant. He spoke to him and almost immediately, J. Haddow, the switch attendant at the tandem belt came outbye. Haddow had seen the framework of the conveyor moving outbye and was making his way out of the pit. At that moment all three heard a “terrific roar” and the trunk belt began to move outbye down the road.

Houston at once took the men with him and turned up the heading on the rise side which lead to the borehole from the surface and from there made his way into the return airway to the top of the Garrowscairn No.3 Dook. From there he went across to the telephone at the end of the West Mine and sent messages to each of the district fireman telling them to withdraw their men immediately. He then went out along the West Mine where he met two men, A. McLatchie and W. Walker running inbye. They had tried to get out but had found the road closed by a mass of sludge. Houston went back to the inbye end of the West Mine where he collected the firemen and their workmen. It was then established that the following men were missing:

Daniel Strachan, fireman in charge of the No.5 Section, John McLatchie, shotfirer in No.5 Section, William Howatt, switch attendant, John Dalziel, loader attendant and the nine miners who had been working in the three places off the No.5 Heading.

Meanwhile, a party of men under the leadership of J. Craig, Garrowscairn Section fireman, and S. Capstick, shot firer in the Turf Coal had gone exploring up the return airway down which Houston had recently come. These men had gone to see if it was possible to get out to the surface but had found all roads blocked with sludge. Fortunately, the telephone from the pit bottom to the surface remained in working order and Houston was able to inform the manager of the position. A second exploring party was organized under the leadership of Capstick to go into the No.5 section by way of the return to try to locate the missing men and to see by this time if any road had opened to the surface. This party soon returned without finding any trace of the missing men and confirmed that there was no escape in that direction. This meant that 116 men were imprisoned.

In the meantime, the three workmen who had earlier been directed by Houston to go to the surface to help with the erection of the fence, had left the pit. They went over to the hole in the field with two surface workers. The party had just started to erect the fence when the ground in the vicinity started to subside rapidly, the ground flowing in from all sides and the hole extended rapidly. Mr. W.C. Halliday arrived at the colliery about 7.30 p.m. in response to the message from Houston. He went to the surface to see the hole and at once got in touch with the agent. He then returned to the field and the hole was getting bigger. He sent for Cunningham, one of the men who had got out of the pit and asked him if he would go back down the pit and get in touch the overman and tell him that the subsidence in the field was getting bigger. Well knowing the danger, Cunningham at once volunteered.

The manager described the crater as water flowing down a sink. He then went to the pit and when he got there received a message from Cunningham at the pit bottom telling him that he had made several attempts and he could not get up into the section because the roads were filled with sludge which had driven him back to the pit bottom. The manager instructed him to tell the firemen to withdraw the men from the pit and bring them out. He then went underground himself accompanied by Cunningham. They found the road blocked to the roof with mud near the junction of the North level and the West Mine. They tried to get up the return airway but found it also blocked with mud. Mr. Bone then came down the pit and it was at that time that Andrew Houston telephoned out saying that he had all the workmen with him except for those from No.5 Section. The manager and Cunningham made several more determined efforts to get inbye but found it impossible. An attempt was made to deal with the mud at the pit bottom by filling it into hutches and winding it up the pit, but the sludge kept slowly oozing outbye and in the end reached the pit bottom and further efforts to deal with it had to be abandoned. In the course of the next 24 hours the sludge rose 16 feet up the winding shaft.

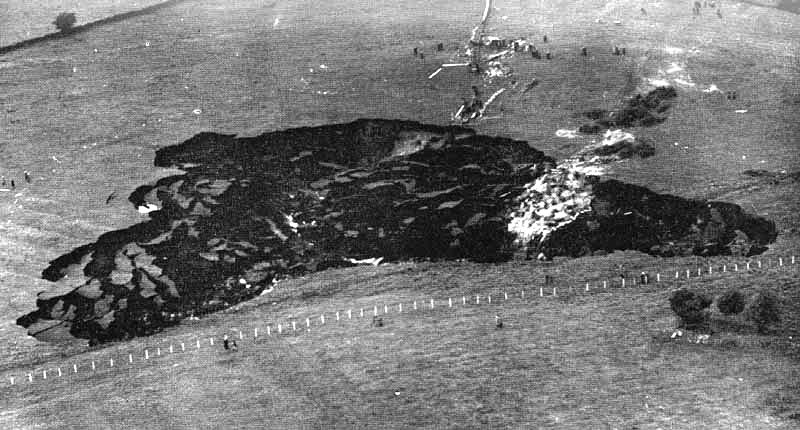

The surface subsidence had increased until the area involved was approximately 2 acres in extent and 40 to 50 feet in depth. In an attempt to prevent the moss or peat running into the pit, bales of straw and hay, trees and pit timbers and hutches were thrown into the crater. This effort was ineffective though some of these articles were later found in the workings. The assistance of the local Fire Brigades was obtained and portable petrol pumps were installed at strategic points around the subsidence and fresh ditches were dug in order to prevent or reduce the amount of surface water flowing into the crater. In addition several surface drains and a bur were dammed and the outer was pumped into the River Afton. Messrs. Wimpey were called in to secure the side of the hole and to take steps as were possible to make it safe for an exploring party to enter the exposed roadway at the bottom of the subsidence. This work started on the 8th September. By 4 p.m. on Sunday 10th September, a party of six men descended into the workings from the crater, followed by a second party at 10 p.m. but they found that the two main headings were completely blocked at a point 800 feet down.

It was known that Houston and 115 men were at the inbye end of the West Mine and it was apparent that the greater part of the roadways between the shafts and this point were locked by sludge that would take months to clear. News of the disaster reached the higher officials in the Ayr and Dumfries Area and the National Coal Board, representatives of the mineworkers and the Mines Inspectorate and many of them were at the scene in a very short time. The position was discussed and it soon became obvious that the only hope of rescuing the imprisoned men was to make a connection through the narrow barrier, between Knockshinnock Castle and Bank No.6 at the point where the water was pumped through. Andrew Houston was informed of the decision by telephone and he was instructed to explore the Waterhead Dook from his side. This was done and he found that the roadways were open and that the place containing the borehole was accessible.

At the surface a Headquarters Base was established at Knockshinnock Castle, where communication by telephone was available to the trapped men, Bank No.6 and the surface crater. An operational base was established at Bank No.6 Mine and the G.P.O. telephone at this base was reserved for outgoing calls and incoming priority calls by arrangement only. The higher officials of the National Coal Board were told to take all practical measures to minimize the inflow from the hole on the surface to the Knockshinnock Castle workings. Rescue apparatus had been made available at Knockshinnock from Kilmarnock and Auchinlek Rescue Stations and calls were sent out for the local rescue brigades. The Central rescue Station at Coatbridge was put on stand-by readiness.

In view of the distance inbye which was about two miles and the lack of haulage facilities, volunteers were asked to stand by to act as carriers to the rescue teams, to go in with them with the equipment, to wait while they completed their turn of duty and to return with the equipment when they left. The rescue operations fell into three stages. At 11.30 p.m. on 7th September, Mr. G. Rowland, H.M. Inspector of Mines and Mr. McParland, manager of the Bank No.6 Mine, the Superintendent and his Assistant from Kilmarnock Rescue Station, together with two local brigades equipped with Proto apparatus and Novox Revivers, descended the Bank No.6 with the instructions to make a preliminary inspection of the abandoned Main Coal workings. In the meantime, Mr. A. Mcdonald, Area Production manager had staffed the operational base at Bank No.6 office. The Coatbridge Rescue Station Superintendent was detailed to take over responsibility for making and maintaining a rescue team rota as the men became available.

Mcdonald and Richford, the District Inspector of Mines, went down the mine at 2.30 a.m. on the 8th September and met Rowland and his party who were returning to make their report. They had been able to travel along the old road inbye to the point where the connection with the Knockshinnock Castle would be made. The roads were full of firedamp and the inspection had had to be made with breathing apparatus. On this information, a fresh air base was made at a crosscut.

Electricians, engineers and volunteers were now available and detailed arrangements were made on the spot to install auxiliary fans in an attempt to clear the accumulation of gas and by midday on the 8th. September the gas had been cleared up to 300 feet up the right-hand roadway. A sound-powered telephone was obtained from the Coatbridge Rescue Station and this enabled communication to be continued underground and the surface at Bank No.6. About 4 p.m. on Friday 8th. September when the telephone to the imprisoned men was showing signs of weakening; the trapped men were instructed to start to make a passage through the barrier. They were told to halt just short of the old road as there was a risk of the firedamp on the other side fouling their atmosphere. It became obvious that the Bank No.6 side would have to be cleared quickly and urgent measures would have to be taken on the Bankside if the gas was to be cleared in time. A great deal of arduous work went onto improve the ventilation and after five hours, it was found that no appreciable progress had been made.

When the trapped men received their instructions to start making a passage through the barrier, they were warned to keep a small hole in advance and to watch the direction of the air. If it came from Bankside then they were to immediately stop the hole. It was found that, when the hole was made the air travelled from the Knockshinnock side to the Bank pit so instructions were then passed to the rescue men to make the hole larger and pass through food and drinks to the trapped men and arrangements were made to take the food and drink.

On the night of Friday 8th September, Andrew Houston went to the holing to meet the first rescue team and take the, to the trapped men. Up to this time the messages that Houston had sent to the surface said that the Knockshinnock side was free from gas but when he was on his way back with the rescue men he found men erecting a brattice at the top of the Waterhead Dook and two of the trapped firemen told him that gas was collecting there. The trapped men had been told of the large body of gas in the Bank No.6 roads but the news of this gas in the Waterhead Dook was kept from the main body of trapped men in case it should affect their moral.

On the night of Friday 8th September, Andrew Houston went to the holing to meet the first rescue team and take the, to the trapped men. Up to this time the messages that Houston had sent to the surface said that the Knockshinnock side was free from gas but when he was on his way back with the rescue men he found men erecting a brattice at the top of the Waterhead Dook and two of the trapped firemen told him that gas was collecting there. The trapped men had been told of the large body of gas in the Bank No.6 roads but the news of this gas in the Waterhead Dook was kept from the main body of trapped men in case it should affect their moral.

Naturally, with the arrival of the rescue brigade men and food, the men thought that they had nothing more to do but to walk out of the place with the rescue team. Houston had to explain to them about the gas in the roadways of bank No.6 and that it had not been cleared and that it could yet be a considerable time before they were rescued. The food and drink cheered them greatly but the news that they must wait came as a bitter disappointment.

It was not obvious to those in charge of the operations that the clearing of the gas represents a major problem and consideration was given to bringing out the trapped men with self-contained breathing apparatus and instructions were given to collect as many set of Salvus apparatus as possible from all readily available sources. This apparatus was also self-generative and the air could be breathed over and over again as the carbon dioxide was taken out of the exhaled air. The oxygen was carried in a steel cylinder containing 95 litres when fully charged at a pressure of 1,800 lbs. From the cylinder the gas passed valve which delivered two litres per minute into a bag from which it could be inhaled and then through a carbon dioxide absorbing and cooling medium to a mouthpiece. It was intended for half an hour of use and was lighter than the Proto, weighing only 18 lbs.

Following on inspection and a careful review of all the circumstances in the early morning of Saturday 9th September, the face had to be accepted that there was no real progress in clearing the gas from the roads, not was there any immediate chance of success, so a scheme was the formulated for the use of rescue teams of six men to escort three of the trapped men out wearing Salvus apparatus. It was estimated that it would take forty hours to get all of the men to safety but, although regrettable, the men had fresh air and a supply of food and drinks and the plan caused no undue alarm.

It was fully realised the scheme had its risked since the men were not trained to use the apparatus and the hope was that the gas would be cleared and the men could walk out in fresh air. Soon after the holing had gone through, rumours began to circulate about the state of mind of the trapped men. They were restless and puzzled at the delay and there was a rumour that some of the younger men were talking of a dash through the gas filled roadways which would have been suicidal. At this point Mr. D.W. Park, Deputy Labour Director of the Scottish Division of the National Coal Board suggested to Lord Balfour, Chairman of the Divisional Board this it might be a good thing if someone put on a Proto apparatus and went through to join the trapped men in order to fully explain the situation to them.

Mr. Park volunteered to do this. As a boy he had worked in the New Cumnock Pits and at one time had been a member of the local rescue brigade and also had experience as a member of the permanent rescue brigade at Houghton-le-Spring Fire and Rescue Station in County Durham and the men that had been trained there had experience with the Salvus apparatus. He also knew many of the imprisoned men personally including Houston. He was given a medical examination and he joined a team which entered the Knockshinnock workings at 3.40 a.m. on Saturday 9th.September. in evidence at the Inquiry, Andrew Houston said, when he appeared, “Well, I don’t think another man breathing could have come in that would give me more confidence that Mr. David Park”. Mr. Park called the men around him, told the, what was being done to rescue them, calmed their fears and generally restored their morale and so assisted the overmen to restore discipline. His action was largely responsible for the safe rescue of the men.

After addressing the men he had a look round and found that the atmospheric conditions were far from satisfactory. Firedamp was appearing in the area and the percentage steadily increasing. He instructed the captain of the rescue team to in from those in charge of the operations at the fresh air base of this and the situation was much more serious than he could say on the telephone in the presence of the trapped men. There was 3 to 5 per cent firedamp in the general body of the air and unless something was done quickly he thought it would be too late.

It was then realised by those in charge of the operations that drastic measures would have to be taken at once and a new scheme was drawn up by the officials at the fresh air base, McDonald, Richford and Stewart. This was to form a “chain” of rescue brigade men along the whole length of the gas filled roadway on the Bankside, who would pass sets of Salvus apparatus through to the rapped men. a rescue team would enter the Knockshinnock workings and instruct the men in the use of the apparatus, fit them with them and pass them back along the chain. Mr. Stewart returned to the surface or report the proposal and to request that a general call should be made for additional trained rescue men from Lanarkshire to enable the scheme to be put into operation. The principle officials felt that this plan was not in accordance with the Rescue Regulations but agreed with grave misgivings. About midday on Sunday 9th September instructions were given for the scheme to be put in operation.

By 12.30 on Saturday there were five rescue teams at the fresh air base. There were ample reviving apparatus and stretchers, blankets and first-aid men available as well as doctors and medical supplies. One of the imprisoned men was in a very weak state and would have to be brought out on a stretcher and a team was sent through to give him an injection provided by the doctors. It was then decided that it would give the trapped men a great deal of confidence of the sick man was the first to be rescued. A team was sent in with stretchers and blankets and two sets of Salvus apparatus at 12.30 p.m. At 2.45 p.m. the sick man was brought to the fresh air base but buy this time, owing to various delays and incidents, all the five teams at the fresh air base had been used and there would be a further two-hour delay before sufficient teams could be assembled to enable the chain operation to be attempted.

At 5 p.m. the position was as follows, 87 sets of the Salvus apparatus had been brought from the surface to the fresh air base, together with 100 spare cap lamps and more Salvus sets were on the way. A “chain” of man at intervals of a few yards, extended from the fresh air base to the main base where doctors were waiting and 30 stretcher-bearers and food water and hot tea was available at both bases. One of the rescue teams was held for any emergency at the fresh air base and instructions given not to go to the advance fresh air base until a fresh team from the surface arrived at the base. One team was kept at the advance fresh air base and as a fresh team arrived they were sent to the operational zone.

The main operation was ready and a team from the Coatbridge Rescue Station was instructed to proceed directly to the Knockshinnock Castle side, disconnect their apparatus, do all they could to raise the morale of the trapped men and explain the general plan and the use of the Salvus apparatus before fitting each man and sending him out. They were asked to remain of this job without relief, if possible. Immediately afterwards four other teams set off carrying Salvus apparatus and spare lamps with instructions to pass them forward to the Coatbridge Brigade of the Knockshinnock side. They were the to establish the chain when the remainder of the Salvus and spare lamps could be passed forward through to the trapped men.

All the teams were briefed on the following lines:

(a) That the intervals in the chain were to be shortened as fast as trained rescue brigade men became available.

(b) Each new team was to go to the head of the chain i.e. the end nearer the Knockshinnock Castle workings, so that the rescued men with decreasing reserves of oxygen would be place down the chain towards the advance fresh air base.

(c) In the event of any rescue man using more oxygen than the remainder of his mates, he was to return to the fresh air base as an individual, but the remainder of the team was to remain as long as possible.

(d) Stretcher cases were not to be attempted unless authorised from the advanced fresh air base.

(e) Definite instructions were given, that if any man wearing Salvus apparatus collapsed, they were not to do anything to impede the general scheme of evacuation.

(f) As it took twenty-five minutes for a team to travel from the advance air base to where the trapped men were assembled, as a guide for their personal safety, each rescue man was told to allow himself sufficient oxygen to cover the period for his retirement.

Houston drew up a rota regulating the order in which the men were to be taken out. He decided that the older men should be the first to go but as the strain was beginning to tell on some of the younger men, many of them were allowed to go before the older men. As the operation proceeded, two doctors, Dr. Sharp, H.M. Medical Inspector of Mines and Dr. Bannatyne of the Aye County Hospital remained at the advance fresh air base whilst three others, Drs. Gooding, Fyfe and Watson remained at the main fresh air base. All the rescued men were medically examined before they were allowed to go to the surface. About 8.15 p.m. the overman, Andrew Houston, was instructed to come out, leaving Mr. Park in charge of the remaining men, his presence was required in order to ascertain the last know positions of the missing men.

Towards the end of the evacuation, it was reported by one of the returning rescue men that one of the trapped men was suffering badly from asthma and it was suggested that he was brought our on a stretcher. The doctors were informed and suggested that he be given pills and other injection which they provided. A rescue brigade man was instructed and the man was brought out safely without any further trouble.

The last of the men reached the fresh air base at 12.05 a.m. on Sunday 10th September and the operation had taken eight hours. Twenty brigades had been used in the operation. As the Salvus sets were brought to Mr. Park he examined them and discarded quite a number for a variety of reasons. Had he not done this they was a possibility that there could have been more casualties. When the last man had left Mr. Park organised a search with a rescue brigade to make sure the no one had been left and he was the last man to leave.

When Andrew Houston reached the surface he was able to direct operations in the places where the missing men had last been seen working prior to the disaster. Two of the missing men, John Dalziel and William Howatt in the No.1 Heading. It was felt that if any of the missing men escaped the inrush and had taken refuge in the workings on the rise side of the No.5 Heading they would have been found by the exploring parties from the trapped men and would have been rescued along with them. All interested parties came to the sad conclusion that there was no hope of the 13 missing men being alive. A decision was taken that no more rescue brigades should be sent through the escape hole and efforts were then concentrated on an exploration of the crater as the exposed end of the No.5 Heading could now be seen there. It was thought that it may be just possible to get far enough down the Nno.5 Heading to give access to the inbye workings in a further search for the missing men.

The work on the crater to make it safe had commenced on the morning of the 8th September when two exploring parties had reached 800 feet down the Heading. Unfortunately heavy rain had persisted and made worse the precarious sides of the crater. Masses of moss were slowly but continually closing the opening. The gradient of the heading was 1 in 2 and all the roof supports had probably been swept away and due to falls, it was probable that the exploration of the heading would be a dangerous and difficult affair. Efforts were being made to clear the Knockshinnock shaft but operations were very slow.

By Monday 11th September a meeting was held by all representative parties and a decision was taken that no further should be carried out underground until the side of the crater and the No.5 Heading were secured. By this time it was felt that there could be no hope of reaching or rescuing any of the 13 men and that there was no justification for risking the lives of rescuers.

The men who died were:

- John Dalziel aged 50 years, loader attendant,

- James D. Houston aged 46 years, coal miner,

- Thomas Houston aged 40 years, coal miner,

- William Howat aged 61 years, switch attendant,

- William Lee aged 48 years, coal miner,

- William McFarlane aged 36 years, coal miner,

- John McLatchie aged 48 years, shotfirer,

- John Murray or Taylor aged 33 years, coal miner,

- Samuel Rowan aged 25 years, coal miner.,

- John Smith aged 55 years, coal miner,

- ?? Stachan aged 38 years, fireman,

- John White aged 26 years, coal miner.

The report on the causes and circumstances attending the accident which occurred at Knockshinnock Castle Colliery, Ayrshire on the 7th September 1950 was conducted by Sir Andrew Bryan, J.P., F.R.S.E., at the Ayr Council Chamber of the County Buildings from the 7th. to the 10th. November and from the 13th to the 16th November 1950. The final report was presented to The Right Honourable Philip Noel Baker, M.P., Minister of Fuel and Power on the 2nd, March 1951. All interested parties were represented. The inquiry came to the following conclusions:

1). The disaster was due to an inrush of peat which broke through from the surface into the face of the No.5 Heading in the South Boig District from the Main Coal Seam on the night of the 7th September 1950.

2). The No.5 Heading had been driven up towards the surface and had holed through on a deposit of boulder clay, sand and gravel at or near the base of a hollow of channel which had been eroded along the softer parts of the coal-bearing rocks.

3). This hollow had a maximum depth of about 44 feet, was lined with a bed of boulder sand and gravel, above which was a layer of almost impervious mud overlain by a deposit of peat which extended to the surface.

4). The maximum depth of the peat deposit was about 12 feet, of which the top layer, about 2 feet thick, was consolidated above the level of the field drains, the remainder being waterlogged and in a fluid condition.

5). The No.5 Heading holed through when a shot was fired in the breast coal at the face of the heading on the night of 30th August and released a flow of water draining from the surface through the bed of boulder sand and gravel.

6). This flow of water remained almost constant until the morning of the disaster when, owing to an extraordinary heavy rainfall, the flow trebled with the result that it washed away debris under the base of the two hardwood pillars which had been built to give extra support to the props, causing it to collapse. A fall of roof resulted and rapidly extended and so weakened the thin supporting barrier of rock and coal at the face of the heading and next to the base and side of the hollow, that it finally collapsed. The bed of boulder sand and gravel gave way, then the layer of mud, and the peat flowed into the heading.

7). The peat continued to flow for some time and soon filled up miles of the underground roadways and blocked all means of exit from the underground workings to the surface, resulting in the loss of 13 lives and the trapping of 116 other workmen.

8). Although the position of the deposit of peat was shown on the geological survey map of the district and this map had been consulted in the planning department, the symbol indicating the presence of peat in the field concerned in this disaster was overlooked.

9). The field concerned had been visited on several occasions by officials, but they were misled as to the true nature and character of the ground by itÕs superficial appearance due to limited effect of the field drainage system.

10). A proper examination of the nature and character of the ground in the field was not made by colliery management nor by the planning engineers at any time either before No.5 Heading approached the surface or after the heading had reached the outcrop beneath the superficial surface deposits.

11). In my opinion the subject to questions of legal interpretation, this was a contravention of Regulation 29 of the General Regulations, 1920 (Working under Moss, etc -Precautions) in that the No.5 Heading had been worked under a deposit of peat with a depth of cover of less than 60 feet or ten times the thickness of the seam, without taking precautions required by the Regulation.

12). There was a weakness in organization in that insufficient arrangements were made to ensure that the planning engineers were kept adequately informed of the subsequent changes disclosed by the progress of the workings in the No. 5 Heading Section to enable them to check the accuracy of the forecasts in the development plan, made in April 1950, for the district of the mine.

13). In my opinion and subject to the questions of legal interpretation, there was no contravention of Section 67 or of Section 68 of the Coal Mines Act, 1911.

As a result of the Inquiry Sir Andrew Bryan made the following recommendations:

1). a copy of any map and of any relevant memoir published by the Geological Survey and relating to the district in which the mine is situated should be kept in the office of the manager of the mine and also in the offices of the surveying and planning departments relation to that mine.

2). Where the geological map or any boring, mining geological or other records shows the presence of peat or any unconsolidated deposit within, or in the proximity to, the boundaries of the mine, the limits and nature of such deposits should be shown on the working plan of the mine, and the General Regulations, 1920, No. 1423 (Workings under Moss etc. – Precautions) should apply to all working under areas so defined.

3). Before any working approaches within 600 feet of the surface until the nature of the intervening ground between the surface where the nature of the intervening ground between the surface and the expected horizon of the working had not been determined, the manager should obtain the advice of a competent field geologist as to the nature of the intervening ground and should consider such advice in determining which precautions, in any, are necessary before further working in undertaken.

4). No working should approach within 150 feet of the surface until the nature of the intervening ground between the surface and the expected horizon of the proposed working had been determined by boring or other approved means.

5). Except with the permission of the inspector and subject to conditions as he may think fit to impose, any working which is being driven towards the surface or a superficial deposit and had approached within 50 yards of the surface of the base of the deposit should not exceed 10 feet in width.

6). Research should be started to explore the possibilities of a rapid and accurate geophysical or other methods of surveying to determine the thickness nature and extent of all unconsolidated superficial deposits.

7). The provision of some form of simple, light-weight, self-contained breathing apparatus which could be worn by any workman after minimum instruction should be investigated without delay and, when such apparatus is available, arrangements should be made to maintain supplies at all General Rescue Stations or other suitable centres in every mining district.

8). Where practicable, the provision of an “escape” roadway giving direct access to an adjacent mine should be considered.

9). Consideration should be given to the provision of a type of telephone cable for underground use in the mines which will be highly resistant to damage from inrush, inundation and fire.

10.). A suggestions I made in my Final Report on the Explosion at Whitehaven “William” Colliery, (Cmd.7410) namely that consideration should be given to the desirability of providing temporary erections such as tents or prefabricated structures to cope with the accommodation necessary for large numbers of persons employed in rescue and recovery operations at the time of a disaster, should be acted upon.

11). In the National Coal Board organization the status and responsibility of all Planning Engineers, Planners and Surveyors at all levels should be clearly defined in relation to those of Colliery Agent and Managers.

Sir Andrew concluded the report with an expression of thanks to everyone who had taken part in the rescue operations and the inquiry.

The George Medal was awarded to Houston and Park for their conduct during the events following the disaster. When salvage squads eventually were able to enter the pit they found evidence that the missing men had survived the original fall. On a bait tin which had been left by one of Houston’s party, and he had left unopened, a salvage worker found someone had opened it and not a crumb of the contents remained. Later messages were discovered on a conveyor belt signed by Dalziel and Howatt. The message was dated 12th September, three days after the main party’s escape. It was timed at 6.10 p.m. and it informed the readers- “Still trying. We intend to make for No.21 Road” but every exit had been blocked and the mine became their tomb.

REFERENCES

The report of the causes and the circumstances attending the accident which occurred at the Knockshinnock Castle Colliery, Glamorganshire on the 7th September 1950 by Sir Andrew Bryan, J.P., F.R.S.E., and Henry Walker, H.M. Chief Inspector of Mines.

Black Avalanche. Arthur and Mary Sellwood. Frederick Muller, 1960.

Colliery Guardian, 14th September 1950, p.232.

Information supplied by Ian Winstanley and the Coal Mining History Resource Centre.

Return to previous page